Amid protests for democracy, Hong Kong’s ethnic minorities strive to be heard

- Hong Kong’s protests lay bare a paradox for the city’s ethnic minorities: some are welcomed for joining in, others are scapegoated for violent attacks

- While there has been a realisation that minorities have a part to play in political life, old stereotypes die hard, even among those calling for equality

“With this attack we felt that enough is enough,” said Baldesimo, 34, who was raised in Hong Kong and is of Philippine descent. “We have been talking for a long time if we should come out and say something … This time we felt we had to show that a lot of us are not part of that.”

No evidence had come to light that proved the ethnicity of those who led the attack and Sham, the convenor of the Civil Human Rights Front, said he could not recognise the faces or the ethnicities of the assailants on October 16. Still, rumours spread online that South Asians had been paid to do the job, leading to fears that Chungking Mansions, a hub for the South Asian and African communities, and the Kowloon Mosque could be targeted by people seeking retribution.

The attack on Sham had occurred just days before a planned march by the Civil Human Rights Front in Tsim Sha Tsui, the bustling commercial district that is home to both Chungking Mansions and the mosque.

Despite concerns among the ethnic minority community, what happened next was one of the most heart-warming episodes in the more than four months of protests that have rocked Hong Kong.

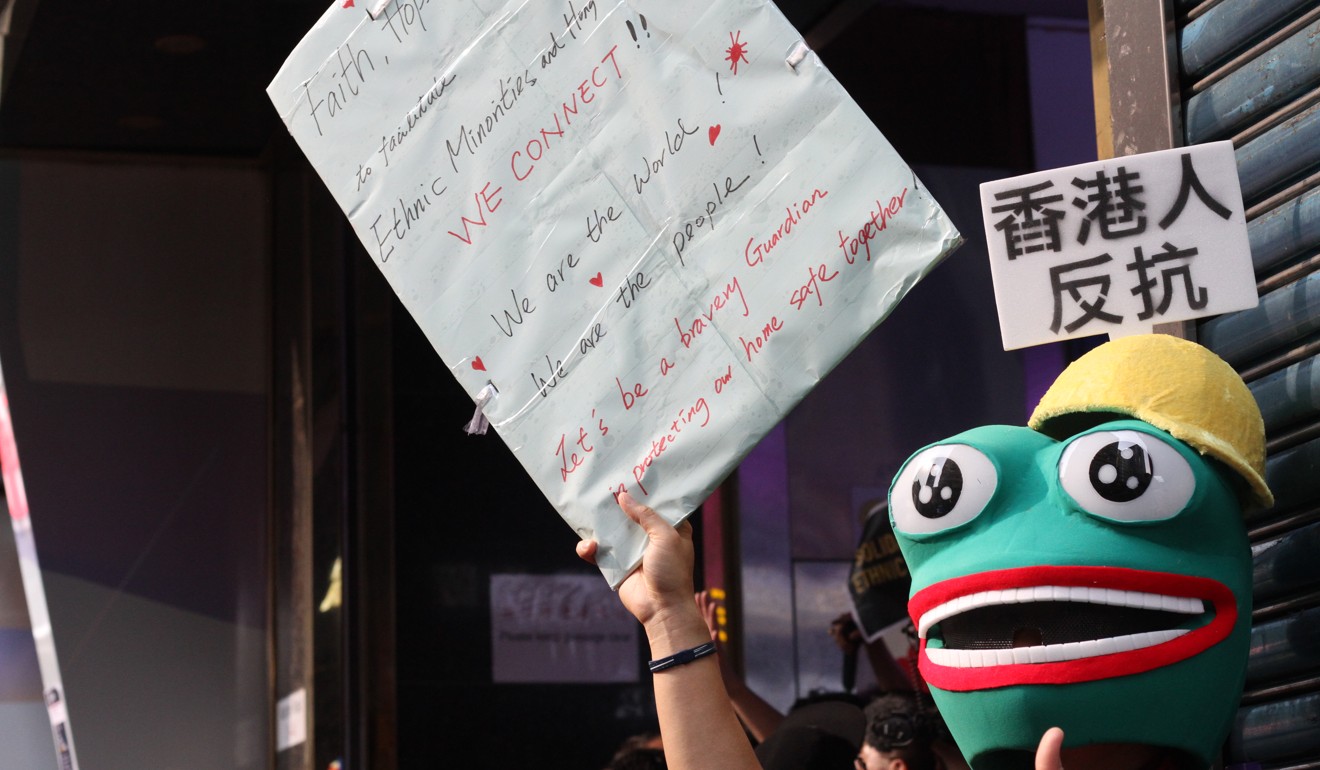

As thousands joined the march, protesters and residents joined arms to guard the mosque, while at Chungking Mansions, a group of ethnic minorities that included Baldesimo handed out water and egg tarts to the protesters and gave speeches to the crowds.

The mood was more celebration than fear, more unity than division. There were hugs and rounds of applause, and a new-found appreciation for the city’s non-Chinese residents.

“We do get a lot of racism in Hong Kong, but we stand here to show you that we are one,” said Baldesimo, wearing a black T-shirt saying “We love Hong Kong”.

That such a sequence of events could unfold so rapidly is testament to the paradoxical nature of life as an ethnic minority in Hong Kong.

Some say the protests have prompted a realisation that ethnic minorities are part of Hong Kong’s social and political fabric; but old stereotypes have also been raised from their slumber, highlighting the plight of a diverse community that often struggles to get its voice heard.

Others see an irony that even among a movement calling for democracy and equal political rights, ethnic-minority protesters are often seen as supporting Hongkongers – rather than as Hongkongers in their own right.

SIGNS OF CHANGE

Louise Bedaña, 20, was born and raised in Hong Kong, after her Filipino father migrated to the city.

Fluent in Cantonese, she knows more about Chinese culture than she does about her father’s home country, yet growing up she often felt alienated and that she was “not a true Hongkonger”.

“Ethnic minorities have been systematically segregated. We attend different schools, we are separated from other Hongkongers, and we experience plain racism,” Bedaña said, blaming the government for the lack of integration. But when the protests against the extradition bill began, Bedaña took to the streets. “Hong Kong is my home and I have an obligation to stand up for it,” she said.

Hong Kong protesters’ demands meant to ‘humiliate’ government: Singapore PM

Since then she has heard various rumours linking ethnic minorities to the violence, not least among them a suggestion after the Yuen Long attack that triad gangs were recruiting ethnic minorities to “carry out their dirty work”. “I think the reason people were so quick to blame ethnic minorities is that [they] have for a long time been associated with gangs and triads,” said Bedaña, a philosophy and politics student at the University of Hong Kong.

While such “baseless association” had been “damaging and harmful”, Bedaña said the protest movement had also been an opportunity for change, with “ethnic minorities finally connecting with locals in ways we have never seen before [as at Chungking Mansions]”.

How the Hong Kong protests inspire Macau’s youth

She experienced this herself at a protest the day after the Yuen Long attack. “I was there by myself and I had heatstroke. I was [on the verge of] fainting and a group of people helped me,” she recalled. “Had it been three months earlier, I do not think they would have willingly and voluntarily helped me.”

“Systemic and internalised racism” had not ceased to exist in the span of a few months, she added. “But with the way that things are looking now, I am hopeful.”

WE ARE ALL HONGKONGERS

This sense of optimism that the protests could be a unifying rather than a dividing force has also been fuelled by those ethnic Chinese who have stepped forward to defend the city’s minorities.

When Joseph Cho Man-kit, a gender studies professor at the University of Hong Kong, heard of the attack on his friend of many years, he was heartbroken. But rather than giving in to pain and anger, he wrote what he calls a love letter to the ethnic minorities of Hong Kong. “I really wanted people to know that even if [ethnic minorities] were involved in the attack, there is a social context that makes them more vulnerable or susceptible,” Cho said.

In his letter, published on Facebook, he wrote: “The wounds on Jimmy’s body are like the ones I and many others [and] discriminatory social structures might have intentionally and unintentionally inflicted on you and the people you care about. Both wounds are bleeding. Without you, there is no hope that they can heal.”

As thousands of protesters descended on Nathan Road, the main artery of Tsim Sha Tsui, many of them expressed similar sentiments.

Eddie Cheng, 76, stood for hours in front of the mosque with a banner that read “be nice to religion”. “I worry that some young kids may do something,” said the retiree. “Some feel that there’s no more hope for Hong Kong, that’s why they came out to fight for freedom.”

Just a few metres from him, another ethnic Chinese protester, Chan, 22, was also holding a banner.

“We are all Hongkongers,” it read. “I am sorry if you have ever felt discriminated against. I am gay so I know how it feels. Please give Hong Kong some time, she is improving.”

Chan, a university student, said the attack on Sham and the claims that ethnic minorities had been involved had prompted him to speak up.

Meet Ah V, the stand-up comic standing up for Hong Kong

“There are many minorities in society, including sexual minorities and ethnic minorities,” said Chan, who was dressed in black. “I know they might face discrimination when they are looking for jobs or when they are dating or just in general. So I am here to remind everyone that we are one big family.”

“As the majority we have the privilege that if we speak, our voice will be louder … this is my responsibility.”

Protesters had plastered walls and traffic poles with messages in English and Arabic, vowing that South Asians would not be attacked.

Further up Nathan Road, at Chungking Mansions, ethnic Chinese protesters applauded and sang Cantonese songs as the minority group that included Baldesimo and her husband Jeffrey Andrews led the chant: “We are all Hongkongers”.

THIN LINE

For Andrews, 34, the city’s first ethnic-minority social worker, the event was a “life-changing experience”.

“There were many ups and downs in the past few days, from visiting Jimmy to threats to the mosque … But what happened on Sunday was a big moment,” said Andrews. “Whoever thought of causing the worst race riots in Hong Kong did not anticipate this. The community is even closer and people know that we are here for real.”

Still, even amid the optimism, Andrews, a third-generation Indian born in the city, warned that perceptions of ethnic minorities could be volatile.

Others have expressed the same concern. “During the months of protests, I saw that finally there was a bridge between us and acceptance to call us Hongkongers. But even as the bridge forms, I’m afraid it’s going to snap again, in an instant,” Jianne Soriano, 24, a Hong Kong-born and raised Filipino who is a writer and youth advocate, said on Twitter.

For now, Andrews is trying to keep the momentum. On Friday his group organised cultural tours of Chungking Mansions and he is encouraging ethnic minorities to register as voters ahead of the district council elections on November 24. “We no longer want to rely on someone else to fight for our rights … We need to take ownership of the city,” he said.

Puja Kapai, an associate professor of law at the University of Hong Kong, said ethnic minorities faced a “paradox”.

“We have a group of people who have sought to argue that they are Hong Kong people, that this is their home, that they contribute … Yet, the media and other narratives around them tend to peg them as outsiders, excluded, marginal or as a burden,” Kapai said.

It’s not just Hong Kong, Asia has a rich history of protests: here are 5

But the welcome was qualified, said Kapai. They were “welcomed because they are standing with Hongkongers, as people showing international solidarity with the movement – not as Hongkongers … People feel a sense of solidarity and inclusion, but the premise of it is still grounded on that lack of acceptance”.

Negative news and a lack of representation in pop culture are part of the problem.

“We don’t count as Hong Kong people in our own right, but when there is violence and trouble, we are ready to be scapegoated – largely because of this idea that we are so poor that our political affinity can be bought,” said Kapai, whose family of Indian descent arrived in the city in 1953.

The scholar said many of the rumours linking minorities to protest-related attacks were unsubstantiated and that it was hard to pinpoint their source, but that similar things occurred in places where there were strong movements against those in power.

“Who does this narrative serve? Obviously those who are against the protesters … It could distract the energy of the vandals away from the Chinese-owned businesses and government facilities and redirect anger to South Asian businesses, work or religious places,” Kapai said. “When you want a movement to be completely divided and messy – you throw race and religion … and that’s very dangerous.” Other than being blamed for violent episodes, ethnic minorities have featured in other stories about the protests, such as when the city’s railway operator floated the idea of hiring Gurkhas, supposedly because the language barrier would make Nepalese workers less likely to react to verbal abuse. The operator of the city’s MTR metro system has come under fire from some protesters who accuse it of complicity with the government for closing stations near protest-hit areas. Vandalism of MTR stations has become common on protest days.

Meanwhile, the emergence of protest graffiti using Islamic expressions, and jokes that suggest converting to Islam as a way of getting around an emergency law banning the use of face masks in public have also angered the community.

Some scholars and residents said ethnic minorities had been politically instrumentalised, especially during periods of protest and at election time.

“It’s a regular pattern and they [some politicians] have been very deliberate at engaging with the ethnic-minority community at the right time,” said Kapai.

FORGOTTEN CONTRIBUTION

Although their contribution to the city may often be overlooked, ethnic minorities have played an important role in Hong Kong society for over a century. Many Sikhs, Nepalese and Indians were employed as policemen and soldiers under British colonial rule; and ethnic minorities have also contributed to institutions such as the Star Ferry, the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, and the University of Hong Kong.

While some families have been here for several generations, others arrived far more recently.

Hong Kong also has a population of a few thousand asylum seekers, mostly from African and Asian countries, who are not allowed to work and who cannot be resettled in the city.

While Hong Kong grants religious and cultural freedoms, the city’s relationship with its non-Chinese groups has long been marked by misconceptions. Several studies have also pointed to systemic and structural problems, including lack of equal access to education, public services as well as employment.

Kapai said society also had a tendency to see ethnic minorities as one homogenous whole, rather than as a variety of diverse groups and individuals.

DIVISIONS WITHIN DIVISIONS

Much like the population at large, Hong Kong’s ethnic minorities hold no single view of the protests.

“The ethnic-minority community is also torn apart. Some people support the protesters, others support the government and the division is quite vocal,” said Yasir Naveed, 29, who was born in Pakistan but has spent half his life in Hong Kong.

Naveed joined the first protests against the extradition bill, but stopped attending as the demonstrations increasingly descended into violence. “Many think it’s better not be part of the matter because whichever side you take, it can be dangerous,” he said.

Many ethnic minorities feel that protesting or being too vocal politically is more risky for them than for the ethnic Chinese. Some fear being profiled by the police, others fear isolation and stigmatisation within their own community.

What next for Hong Kong’s extradition bill protesters?

Alizai, 45, a trader from Pakistan who is married to a local Chinese woman, also stopped protesting after attending the initial demonstrations in June.

“My wife and I have a five-year-old son. As an ethnic minority, I know I can be easily profiled by the police, so I can’t be out there,” he said. “If the government doesn’t listen to the majority of the local people, why would it listen to the ethnic minorities?”

The issue has even prompted thoughts of relocation. “I see my wife crying almost every day. She thinks there’s no future in Hong Kong. We have been talking about leaving, perhaps to my home country.”

Hassan, 32, an NGO worker from Somalia who moved to Hong Kong about two years ago, is another who supports the protests but avoids attending them as he feels he has a higher chance of being detained.

“We are not worried about the protesters. We feel concerned about the authorities,” he said.

Hassan said that before the protests started he would often be stopped and searched by the police for no reason, especially on the MTR. But now the authorities’ attention seemed to have shifted. “Now they stop Chinese-looking people.”

The fear that one arrest would reflect badly on the whole community tended to make minorities acutely aware of legal boundaries, said social worker Andrews. “Many of us worked so hard to be part of the so-called mainstream society that we don’t want to risk that.”

Due to language barriers, others in the community simply don’t have enough information to form their own opinions and participate in civic or political activities. This is particularly a problem with elections approaching, with some candidates handing out leaflets in only one language. “Many ethnic minorities are unaware of things happening,” said Ansah Malik, a social worker of Pakistani descent. “Most information is in Cantonese and even if it’s in English it may not reach many families.”

THE OTHER STRUGGLE

With the protests evolving into wider calls for democracy – the extradition bill was formally withdrawn by the Hong Kong government this week – many in the community wonder when the spotlight might fall on their own struggles for political rights.

Domestic workers, most of whom hail from the Philippines and Indonesia, have fewer rights than most who move to the city. Unlike other groups, they are not entitled to become permanent residents after seven years, a fact that has left many feeling invisible. Yet they, too, have been affected by the protests. Some have had their time off cut while rumours have spread that some have been arrested.

“We can’t vote, we live on temporary visas, our voices don’t count … Yet there have been false news reports about some of us being detained,” said Eni Lestari, the chairperson of International Migrants Alliance, who comes from Indonesia but has spent half her life – she is in her 40s – working in the city as a domestic helper. “This creates panic and everyone is uneasy,” she said, calling on the consulate to clarify the arrest rumours.

Another union leader, Shiella Estrada, 59, from the Philippines, who has been working in the city for more than 20 years, said: “We are all praying and hoping for the government to introduce some solution and bring back peace.

“As a mother and a worker, it’s painful for me to see them fighting for their future like this.”

Some hope that as the protest movement evolves, Hong Kong can start a conversation about democracy that reflects the city’s diversity.

Amod Rai, 40, a teacher from Nepal who has been in the city for about two decades, is among those who have stayed away from the protests but has watched their evolution with interest.

He said Hong Kong’s system “oppressed ethnic minorities” because non-Chinese faced more hurdles in winning top political jobs – a point that had been missed by both government supporters and protesters demanding democracy.

But “diversity and multiculturalism should be fundamental elements” in any such system, he said.

“Everybody’s rights should be secured,” said Rai. “What kind of democracy are they asking for if we are not represented?” ■