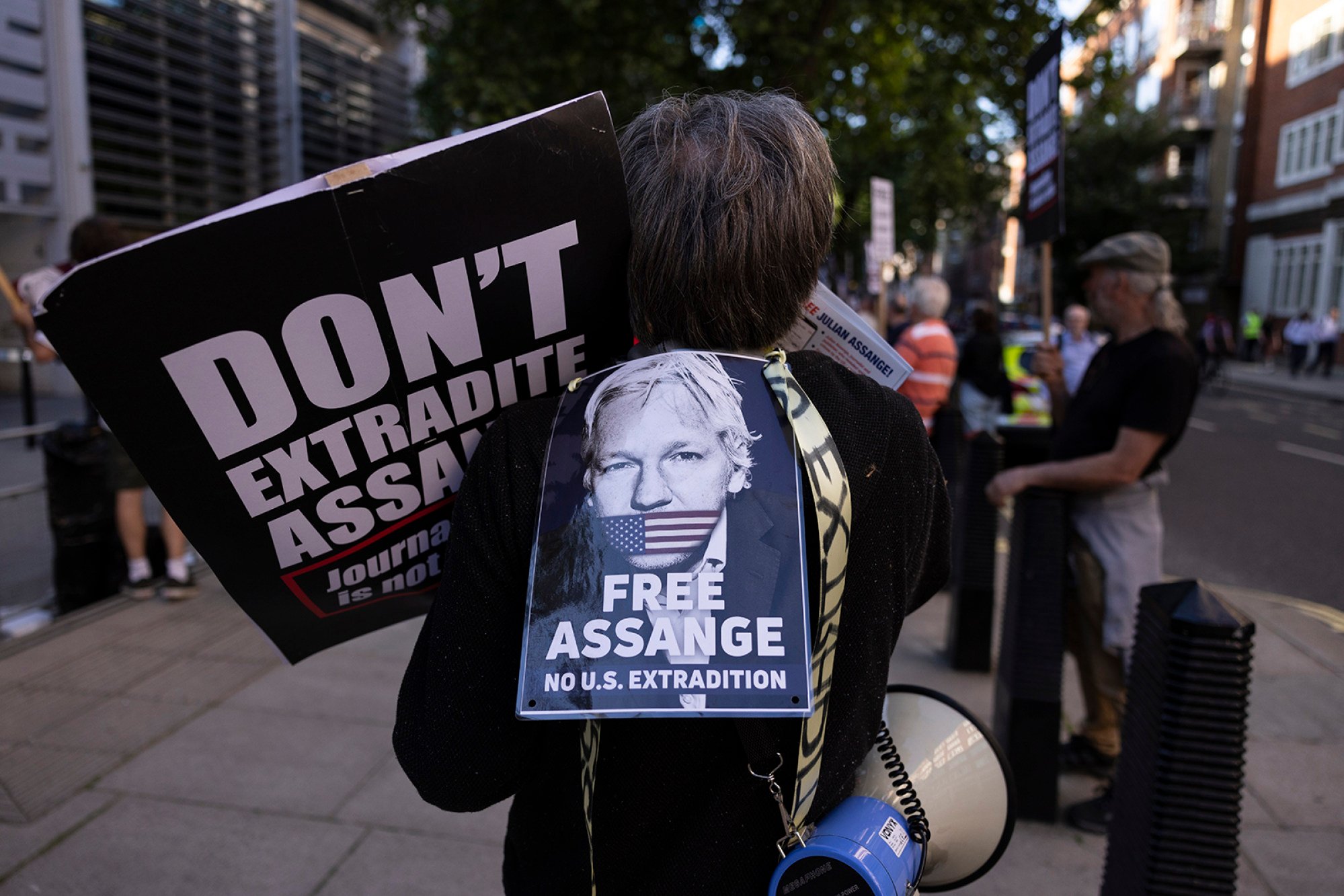

As US-Australia ties deepen, are calls to free Julian Assange just ‘mandatory rhetoric’?

- Australian lawmakers have been piling on the pressure recently for Washington to end its persecution of the imprisoned WikiLeaks founder

- Even Albanese says it’s ‘gone on for too long’. But observers say the PM will ‘look weak and ineffectual’ without actions to back up his words

While the two countries did agree at the annual AUSMIN forum to a “combined intelligence centre” that would embed more US intelligence personnel within Australia, there were also signs of growing impatience at Washington’s lack of a quid pro quo.

“Make no mistake – the situation Mr Assange finds himself in is not in any way about his actions threatening US national security,” senator Nick McKim said in Australia’s parliament on Wednesday last week, calling the case a “matter of public importance”.

He said the US’ behaviour was motivated by “their utter humiliation and embarrassment that Mr Assange exposed the US military as having committed murder and war crimes”.

Through Assange, the US was effectively warning journalists not to report on its war crimes and attempting to deter future whistle-blowers, McKim said.

‘Dragged on for too long’, Australia’s Wong says of Assange WikiLeaks case

Another senator, Peter Whish-Wilson, accused Blinken of lying and propaganda, saying that the US government had already provided evidence that the leaks did not result in damage or harm.

Senator Gerard Rennick said he’d been “led to believe” that former US Secretary of State Robert Gates had dismissed the idea that the leaks put any US or Australian troops at risk.

“I do believe in the role of free speech and I do think that we need to hold governments to account for the decisions that they make when they start to go into other countries,” he said.

He added that the Iraq war had been “a gross violation of human rights” and a “set-up”.

Australian lawmakers have stepped up the pressure on the US to abandon its pursuit of Assange in recent months, including with an open letter in April signed by nearly 50 MPs and senators.

‘Mandatory rhetoric’?

“We’re hosting their armed forces, with US bases on our soil. We’re going to host their nuclear submarines, and we’re going to embed their spies into our military apparatus. We’ve been here time, after time, after time, for the US,” McKim said. “It is time that Australia made it clear to the US that this relationship is a two-way street.”

Australia presses US to drop extradition case, free WikiLeaks founder Assange

But prominent Australian international-relations expert Clinton Fernandes said the Albanese government had no intention of testing its relationship with the US.

“To the contrary, [the AUSMIN meeting] confirmed a deepening of the relationship, with closer intelligence and space cooperation,” said Fernandes, who is a professor of international and political studies at UNSW Canberra.

Australia, as a “sub-imperial” power, had long benefited from the “rules-based international order” built by countries like the US and Britain, and it was not about to change that, Fernades said.

“[Australia] was born on the winning side of the global confrontation between Europe and the peoples it colonised, and the organising principle of Australian foreign policy is to stay on the winning side,” he said.

Comments about Assange made by the Albanese government so far were “mandatory rhetoric”, Fernandes said, adding that the senators who spoke in parliament would effect little change to the status quo, especially since they were in the minority.

Scott Burchill, an honorary fellow in international relations at Deakin University, said Albanese was even more pro-Washington than former Australian prime minister Scott Morrison, who led a government that pushed a “tough on China” strategy.

“There is support for Assange across the parliament, but the Americans are digging in their heels and Albanese is not prepared to use his leverage to pressure the Biden administration,” Burchill said.

Albanese was unlikely to use any leverage with the US unless not doing so would cost him political support, Burchill said, although there were growing signs the Australian public was becoming increasingly concerned about Assange.

“He will look weak and ineffectual if he cannot get his closest ally to play ball. All the odes to ‘shared values’ and a ‘close friendship’ look hollow,” he said.