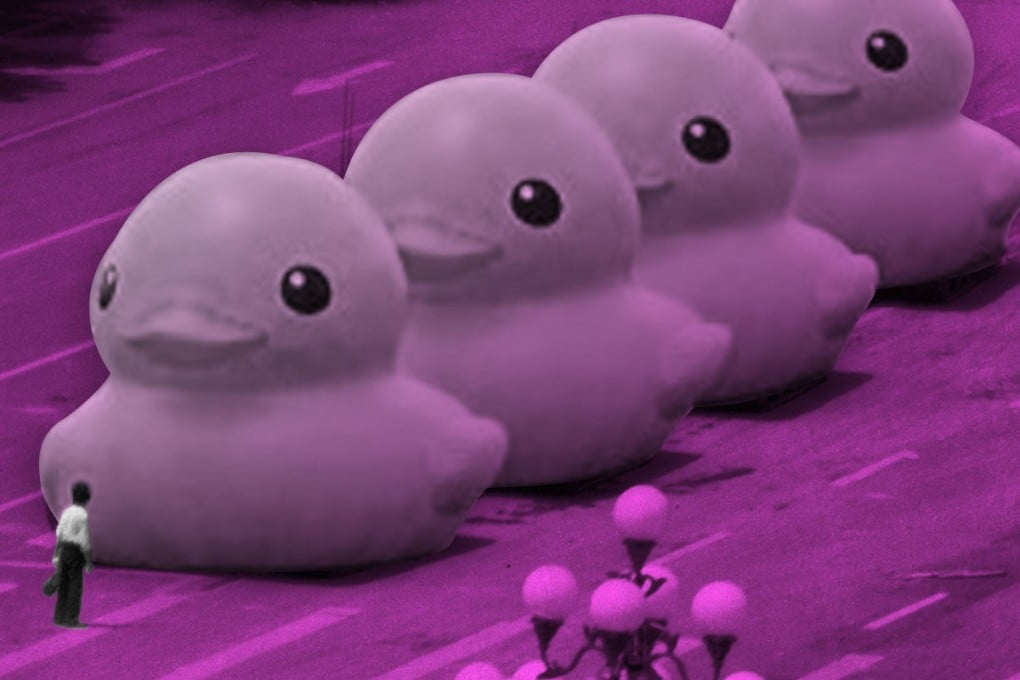

Anything from rubber ducks to iPads are being used to keep the memory of Tiananmen alive

Censors work overtime cracking down on obscure memes that might reference the Tiananmen Square crackdown

Chinese internet users have many ways to refer to June 4, 1989. Some call it May 35th. Some write 6489 or 8964. Others turn to mathematical equations to refer to those number sequences: 32x2, 88+1, 65-1, 2^6.

But the effort to obliterate the event from China’s collective memory doesn’t stop there. Pictures, expressions and anything else that could potentially remind people of the event can disappear from social media platforms such as WeChat and Weibo in a matter of seconds.

To avoid censorship, savvy online users have been disguising the event in memes. Instead of putting up real photos from the protests, they concoct their own, with many referencing the famous Tank Man -- including one famous meme that replaces the tanks with rubber ducks.