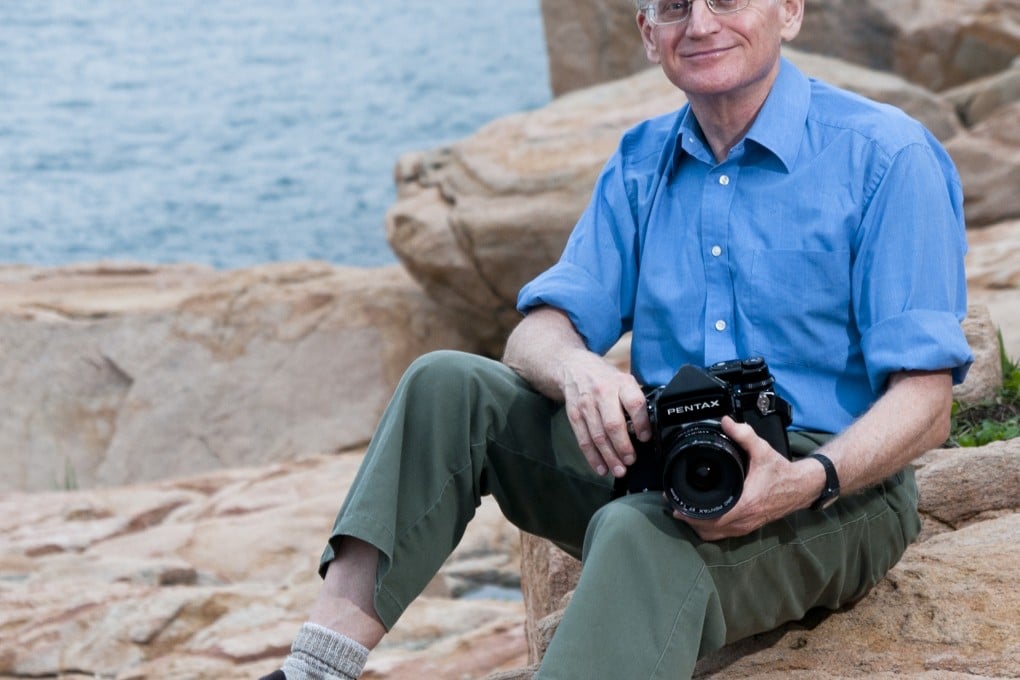

Edward Stokes, Hong Kong photographer with a passion for the history of his craft

Raised in Hong Kong, Stokes knew from a young age he wanted to be a photographer but worked as a teacher, like his father, while he learned the craft

My father was here at the end of the [second world] war. He'd been an officer in the Australian navy and fell in love with Hong Kong. So he returned with a young family in 1953. I was a five-year-old when we came here [from Australia]. It was a Hong Kong beset with refugees, poverty-stricken people fleeing China and many squatter estates. Our life was completely different. My father worked for the government as a teacher, later as a headmaster. And we grew up in Repulse Bay, Mount Nicholson and The Peak. Lovely places, wonderful for children to grow up in - we were very fortunate. I think my love of nature and landscape goes back to those years.

I'm quite sure the visual drama of Hong Kong affected me in a subconscious way; its hills, its city areas, views over the harbour. Having a view was part of life as a child, living where we did. If you grow up in a suburb in Australia or Britain, a view is a rare thing. As a youngster and teenager I took photographs in Hong Kong. I still have some of them and, looking back, I can perhaps see the glimmerings of a photographer's eye.

I studied at the University of Oxford [in Britain], then became a primary-school teacher in England before returning to Australia in 1975. In my heart I had already decided I wanted to become a photographer but I continued teaching for a number of years to buy time to learn the skills of photography.

In my final year of teaching, I ran a one-teacher school in a tiny township called Pooncarie - 'Population 48, Tidy Town 1981' the town sign read. Ed Stokes the teacher, with my wonderful cattle dog who roamed with me in those days - and 10 country, pre-television children, full of energy, activity and imagination. But, of course, the life was socially isolated because it was a 200-kilometre drive to the nearest town, Broken Hill. And in bad weather, after rain, the dirt roads were closed.

But it was a real eye-opener on what childhood can be when children are left to develop on their own without the daily onslaught of television.

My first book, called United We Stand: Impressions of Broken Hill, sprang from my fascination with the [town's] outback community. I started looking at old photographs of Broken Hill and found scattered, eclectic images in libraries. I heard about a rare collection owned by a miner. His father had been an amateur historian in the 1930s and had found a cache of glass negatives in a house that was about to be demolished. Wonderful images, kept in an old metal case. So I set out to record the memories of people in their 80s and 90s, who were young adults when these photos were taken, in 1908.

The book became a synthesis of the photographs by James Wooler and the oral history. These people were miners who went underground with candles; bullock drivers; and women who had given birth in tin cottages. Within a few years, most of them had died. And that was the whole purpose of the book, to preserve their memories.