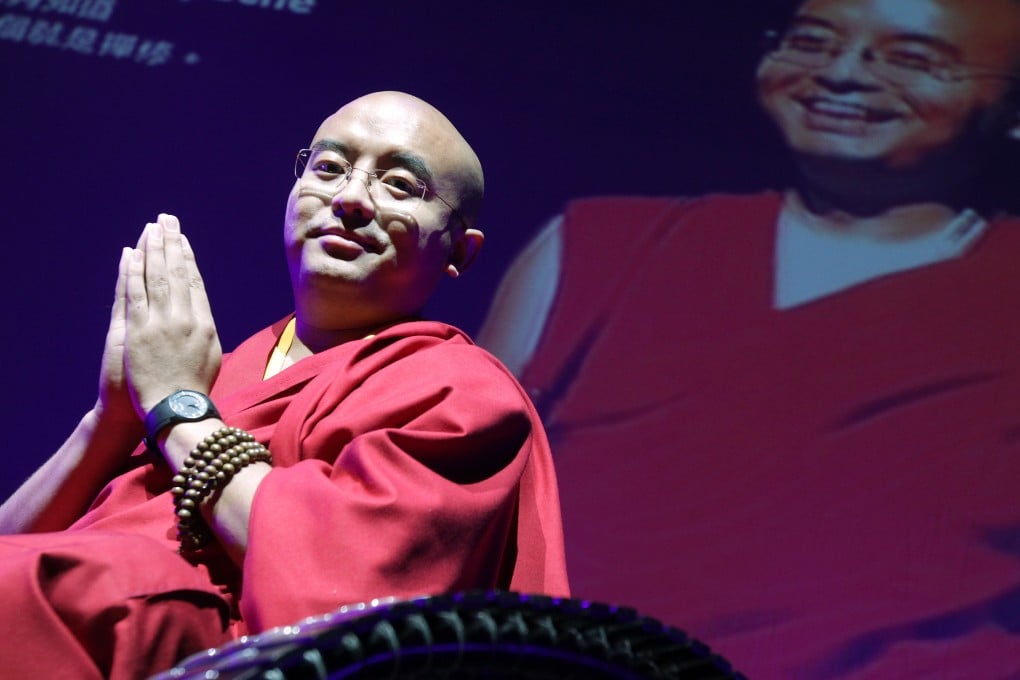

Many happy returns: Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche on power of meditation

Tibetan Buddhist master Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is possibly the world's happiest man, according to scientists, who initially thought their brain scanner was faulty. He's had lifetimes of practice; Rinpoche is an honorific given to reincarnated lamas and means 'Precious One'.

About a decade ago, Mingyur Rinpoche volunteered to have his brain tested alongside eight other monks, all of whom had spent more than 10,000 hours meditating, at the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behaviour at the University of Wisconsin in the US.

'They put me in a huge scanner in the shape of an enormous white coffin,' he says, describing his experience in the functional magnetic resonance imaging machine. 'It was very narrow, cold, dark and noisy. The scientists spoke to me through headphones and asked me to meditate on 'open present', 'concentration' and 'compassion' for 90 seconds each. During this time, they'd send noises of babies crying, children screaming and other things that might cause an emotional response. It went on for two hours.'

Neuroscientist Richard Davidson and his colleagues studied the brain activity of the monks in both meditative and non-meditative states. The findings were extraordinary. They knew that negative emotions registered in the brain's right prefrontal cortex and positive activity was detected in the left. But when the monks generated feelings of compassion, a standard meditation practice, their left prefrontal cortices showed previously unseen levels of activity.

When they ran the tests on Mingyur Rinpoche, his baseline activity was farther to the left than anyone else, so much so that they thought the machine was malfunctioning.