Selden seen

The chance deciphering of an ancient map in Oxford University’s Bodleian Library has generated a flurry of excitement among maritime historians. Vanessa Collingridge explains why it is changing perceptions about Chinese trade during the Ming dynasty

It was half an hour before closing time at Oxford University’s Bodleian Library and historian Robert Batchelor was finishing his research before catching a plane home, from Britain to the United States.

As the library staff tidied up around him, he briefly turned his attention to a document described as, “A very odd mapp of China. Very large, & taken from Mr Selden’s [collection]”.

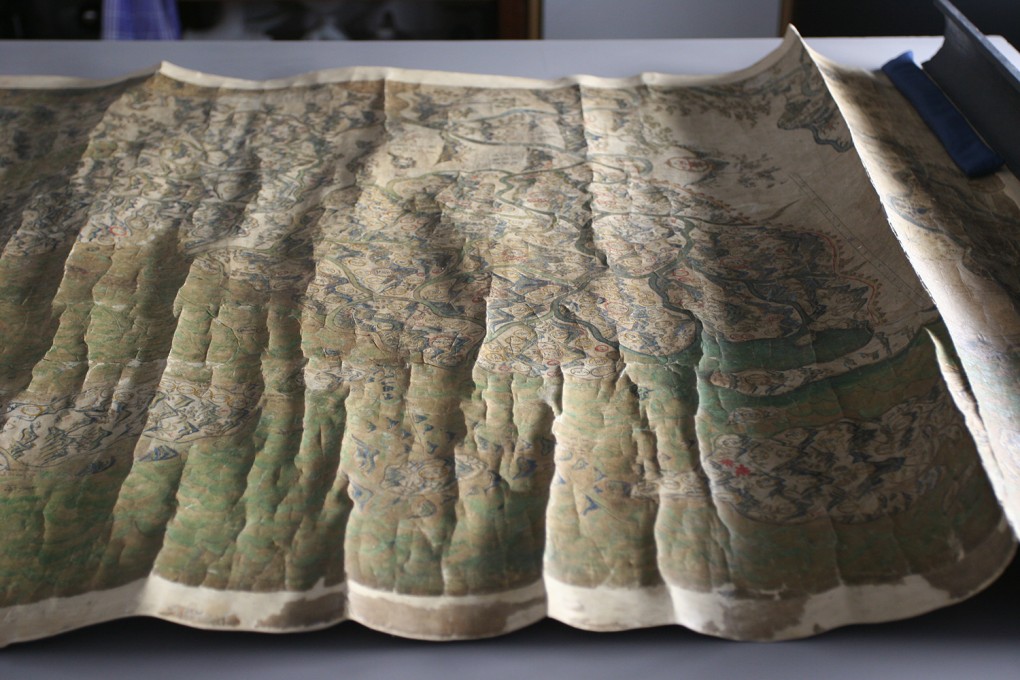

That description, written almost 300 years earlier, fairly accurately summed up the giant manuscript map that had been carefully unrolled before him. One metre wide and 1.5 metres tall, badly crumbling sections revealed a hand-drawn and coloured map of Asia. For three and a half centuries – since its arrival in the Bodleian in 1659 – people had come to look at this curiosity and marvel at the prettiness of its design and colour. But Batchelor knew in an instant that there was much more to this map – and that he had struck gold.

Furthermore, it wasn’t just the trade routes that marked this map as extraordinary; it was also the radical way in which China was depicted that grabbed Batchelor’s attention and made it one of the most exciting discoveries of recent years, for the Bodleian and oriental scholars across the world. In official or scholarly Chinese maps from the period, China normally occupies the whole of the frame, asserting loudly to the viewer that China is the whole world and nothing more need be known. But this map lays out the whole of eastern Asia, with China nudged to the top: its focus is not land at all but the South China Sea and everything that lies within its reach – the first known map of its kind to show this and certainly the only surviving map to do so.

David Helliwell, curator of the Chinese collections at the Bodleian, was there, in January 2008, when Batchelor made his discovery.

“It was wonderful to have that happen on my watch,” says Helliwell.