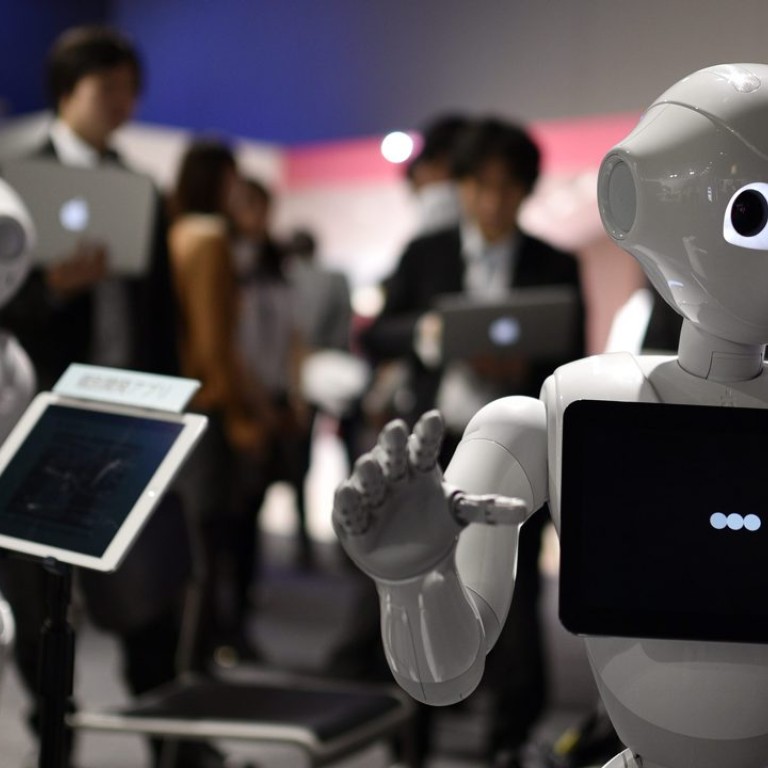

Workers are ready for the robot revolution, but are their managers?

Many of the tasks managers devote time to are candidates for automation

Do workers welcome the new era of robots? It turns out they do. Five times as many think digital will improve their job prospects than those who say it will worsen them. And those who believe digital will improve their working experience outnumber the pessimists by 10 to one, according to global research by Accenture Strategy.

Should such enthusiasm surprise us? Perhaps not. Our new measure of the digital economy indicates that 27 per cent of China’s employment can be considered as digital. That means there is already a large proportion of employment in which digital skills are significant.

In Hong Kong, we see this in financial services – with insurance companies increasingly offering ongoing customer service digitally. Wealth managers have been using robo-analysts to provide financial advice to banking clients. In Southeast Asia we see new intelligent systems bringing not just greater productivity but greater precision to agriculture thanks to sensors, drones and other technologies. And smart glasses are helping field workers to access data and instructions as they repair equipment. These innovations are not making super humans. They are making humans super. Artificial intelligence augments the work they do and helps them do it better.

It’s no wonder that senior executives share the optimism of their employees. But there’s a challenge. Caught in the middle are managers, those who have to implement this significant change. And our recent analysis of managers shows that this critical body of employees has concerns.

We need to encourage experimentation to mould those systems into the fabric of evolving processes and teams

Among the tasks that managers devote most time to today, many are prime candidates for a degree of automation: planning and coordinating work, monitoring and reporting and maintaining standards. Artificial intelligence will increasingly free managers from these time-consuming tasks to focus on work that is more uniquely human, or “judgement work”, which requires complex thinking, interpretation and higher-order reasoning. That could be providing more bespoke services to customers or more personal support to staff. And managers will be liberated to focus more on creativity and innovation.

Yet 57 per cent of the managers we spoke to around the world are uncertain whether they have the skills to succeed in their role over the next five years. Many are concerned about the impact of artificial intelligence on their jobs. Part of their resistance boils down to trust. When asked if they would trust the advice of intelligent systems in making business decisions, only 14 per cent of first-line managers said they strongly agree, compared with nearly half (46 per cent) of executive-level managers.

This calls for a more proactive effort to unite managers and machines. Not only do we need to accelerate the introduction of new intelligent systems, we need to encourage experimentation to mould those systems into the fabric of evolving processes and teams. This approach will show that digital is not something that happens to the workforce but something the workforce makes happen in their organisation.

The other critical step forward is to shift the expectations for management skills demanded in the future. Managers misunderstand the full spectrum of skills needed. More than 40 per cent say that digital and technology skills will be among the most important they will need in the next five years. Less than half that proportion cite people development, coaching, collaboration or social networking.

In fact, stronger interpersonal skills will be paramount if managers are to have the confidence to inspire a more fluid, less structured workforce and to manage the introduction of new technologies in the first place. Above all, these hard to come by skills will be needed so that managers can support their teams as they learn to work with robots and as robots learn to work with them.

Malcolm Hsiao leads Accenture’s technology strategy in greater China