We are woefully unprepared for the tech revolution that will upend our jobs market

As many as 250 million jobs will be lost in China by technological change, 80 million in the US, 15 million in Britain, according to KPMG

Spend an afternoon with a couple of hundred wide-eyed visionary techies, as I did at KPMG’s “Changing Face of Commerce” workshop last week, and the first reflex is to run for the panic button.

It is difficult to reconcile their smiles and millennial enthusiasm with their messages – that 250 million jobs will be lost in China, 80 million in the United States and 15 million in Britain, for example, as our lives are technologically transformed.

Even the more grounded analysts at the International Labour Organisation carry messages that would unsettle most of our communities.

There will be job carnage in some unexpected areas – among surgeons, actuaries, insurance agents and paralegals, for example. As the cost of sequencing a genome has fallen from US$100 million in 2001 to US$100 today, and about 3 US cents by 2020, so the health insurers’ task of anticipating health risks will fall dramatically, according to Steve Monaghan at Gen.Life.

The result: insurance premiums will tumble, the actuaries and insurance agents selling us health insurance products will be laid waste, and early warning of possibly serious illnesses will pre-empt the need for many operations and spill our surgeons’ gravy train.

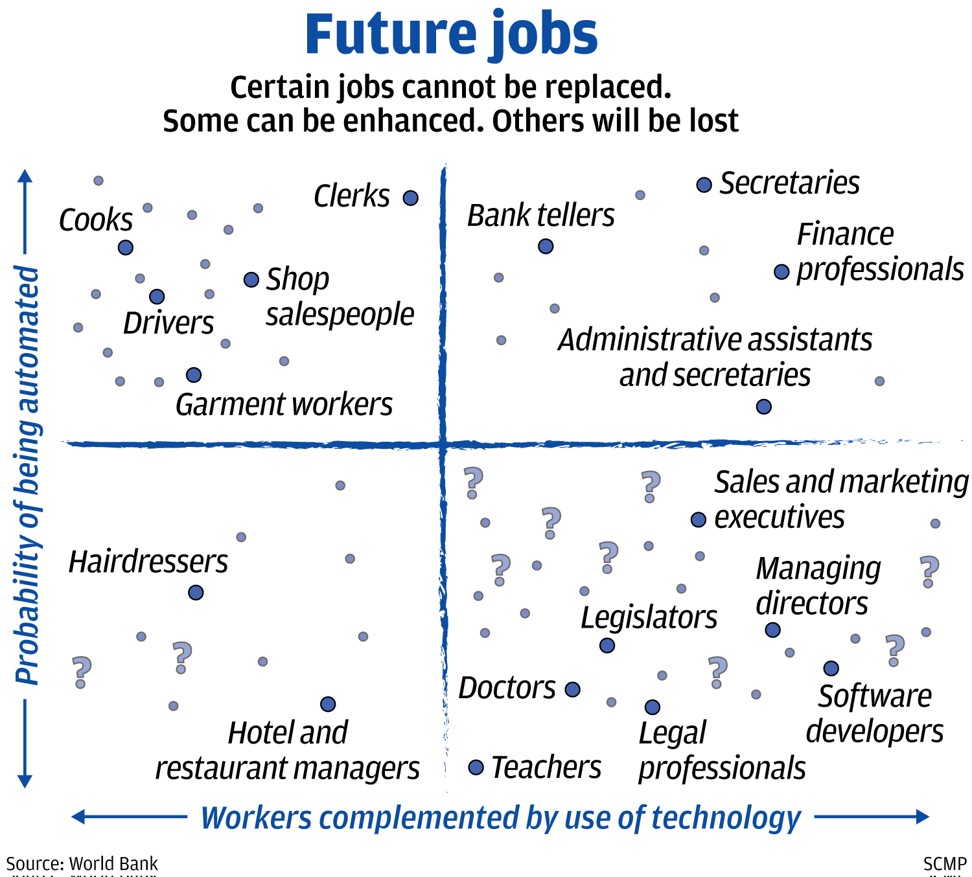

I would have emerged from the KPMG workshop with heart palpitations had it not been for some marvellous comforting perspective delivered at the Hanoi Apec meetings a week earlier by Wendy Cunningham, the World Bank’s chief economist for jobs and labour.The attached chart delivers her much more nuanced message.

But many activities (grouped in the lower left quadrant of the matrix) are not likely to be threatened by the digital revolution. On the contrary, technology is more likely to complement their work, stripping the drudgery out of their jobs and leaving them with more creative and value-adding roles.

These include secondary-school teachers, general practice doctors, sales and marketing professionals, legal professionals and managing directors.

Sadly, it also seems to include legislators and public relations professionals. In short, the more creative, social and problem-solving the work, the less threatened you are likely to be.

Beyond these “augmented” vocations, the World Bank identifies two other groups of beneficiaries.

First, and obviously, the software and applications developers and analysts building the mind-numbing algorithms that will underpin our digital revolution.

Secondly, represented by the question marks that litter the World Bank matrix, are the jobs that do not yet exist, perhaps which we cannot even yet imagine, that will be created by the digital revolution.

So the World Bank message is more nuanced than that of the wide-eyed technology visionary – but only a little less worrying. As we plan to build our future workforces, we will need to develop the skills that technology complements, not those that technology replaces.

For example, driverless cars may be technically ready to roll in the imminent future, but the task of building the roadside infrastructure, and the regulatory regime to manage them, could easily take more than three decades. So, too, with so many “fintech” products that are so exciting the financial services industry.

The World Bank warns that education systems in most countries face wholesale restructuring – away from fact-based learning squeezed into our youthful years and located in big education institutions, towards lifetime learning that is employer- and web-based, built around short, tailored courses and focused on learning-to-learn, digital literacy and social skills.

For this, most of us are horribly ill-equipped and ill-prepared. Titanic battles will need to be fought with those who have vested interests in our present education systems. And the private sector will have to rethink its role in training. At present, most complain loud about skills in short supply but invest little in developing those skills.

First, they need to work imaginatively to create appropriate regulatory arrangements to enable the new technologies to develop.

Second, they need to lead the restructuring of our education systems, in close collaboration with employers and educators.

Third – and perhaps most important – they have to give special attention to safety nets for all those whose jobs are digitally dissolving in front of our eyes.

I wonder how much thought our Hong Kong government has given to these urgent priorities. Not a lot, I suspect.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view