Behind Asia’s heritage hotels, there is a Sarkies

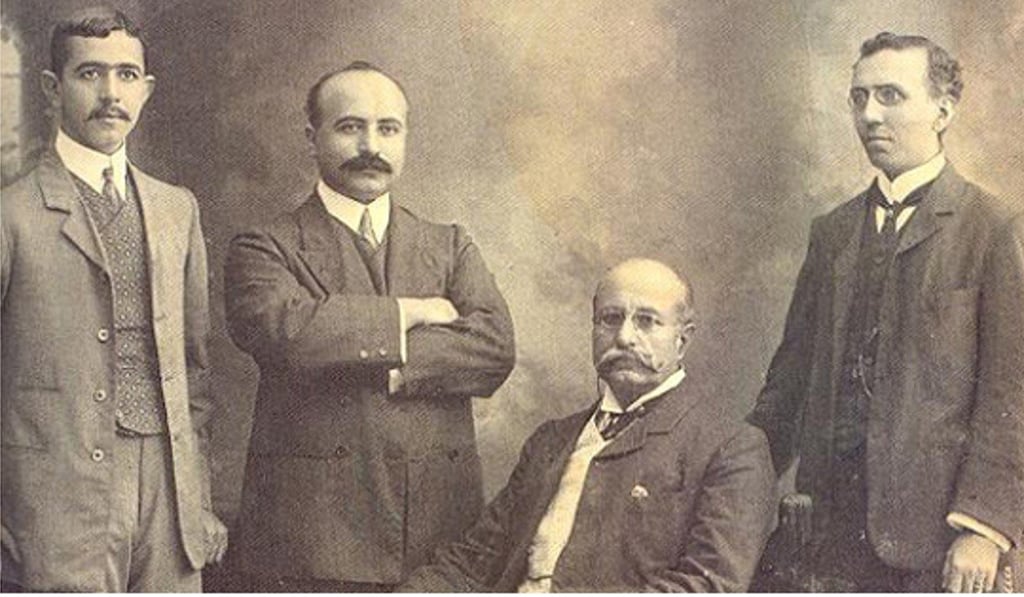

Four of the region’s grand dames – the Raffles in Singapore, the E&O in Penang, the Strand in Yangon and the Majapahit in Surabaya – are built by the family

The word “heritage” is so often appended to hotels today that the term is becoming debased. There are a select few properties in Asia however, that befit the label – hotels in business for a century and more, dating back to the beginnings of tourism in the region.

A measure of this list is that the Peninsula in Hong Kong doesn’t make it – a relative newcomer at a mere 85 years old. The true grand dames include Bangkok’s Mandarin Oriental, the Sofitel Legend Metropole Hanoi and the Taj Mahal Palace in Mumbai. Also making the list are no less than four hotels – the Raffles in Singapore, the Eastern & Oriental in Penang, the Strand in Yangon and the Majapahit in Surabaya – built by one family, the Sarkies.

The Sarkies came to Asia from Isfahan in Persia – modern-day Iran – in the latter part of the 19th-century. Ethnically speaking, they were Armenians, their forebears brought to Isfahan by Shah Abbas the Great in the late 16th-century. In the style of the day, on becoming shah in 1588, he reinforced his rule by brutally replacing swathes of the hierarchy with captured Georgians, Circassians and Armenians. Many of the latter were settled in New Julfa, a suburb of Isfahan, among them the Sarkies family.

In the second half of the 19th-century, Thomas Cook founded the world’s first travel agency. With Europe more widely accessible, the now-familiar search for the less beaten path began.

Even using newfangled steamships and railways, ‘taking passage’ to Asia, took weeks. Once there, the available lodgings suited local habits and diets, not those of pampered Westerners.