Why Asian high-yield bonds are a better bet as rates rise prompted by the US Federal Reserve

Fewer defaults, availability of credit and low sensitivity to US treasuries’ movement mean Asian high-yield bonds could outperform investment-grade bonds in current rate increase cycle

When the 10-year US treasury yield hit a four-year high of 3 per cent in late April, on the back of heightened investor concern about inflation, bankers said Asian high-yield bonds had suffered a brief sell-off.

Spreads for US dollar Asia (ex-Japan) high-yield bonds, as captured by a Bloomberg Barclays index, widened by 100 basis points compared with a low seen in January.

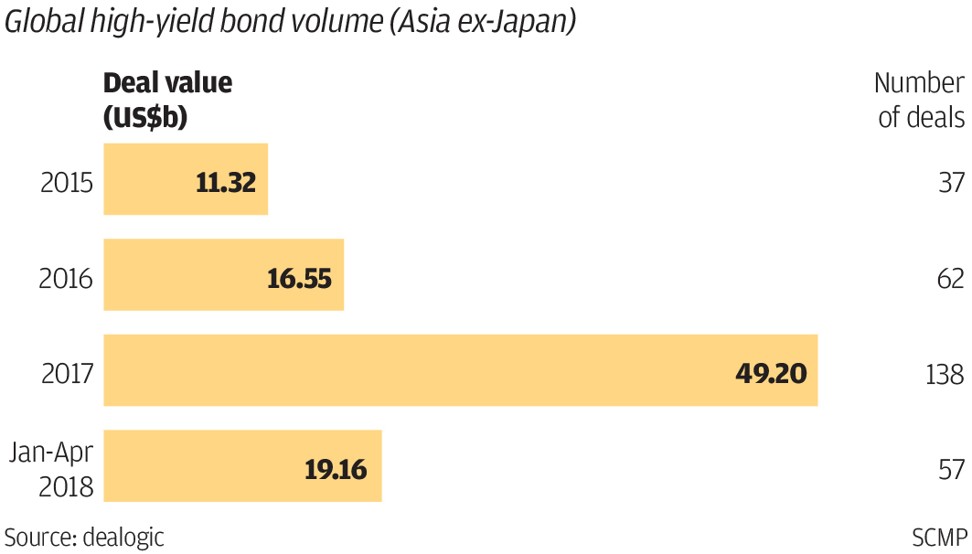

And the sell-off led to some market participants betting that issuance volume this year would lag behind that of 2017, which saw 138 deals totalling US$49.2 billion. The 3 per cent symbolic level of 10-year US treasuries, not reached since 2014, has caused investors to be more discerning about new bond issuances in general, affecting both investment-grade and high-yield papers alike.

Still, the April and May sell-off could well be just a short-term blip. Several Asia bond fund managers said they have made higher allocations to high-yield bonds as they expect these to outperform investment-grade bonds during this rate increase cycle.

This outperformance will be driven by a combination of macroeconomic and technical reasons. The default rate for Asian high-yield non-financial companies will remain low – 1.9 per cent – at end of 2018, Moody’s said in an announcement in February. Meanwhile, companies’ demand for and access to credit remains high globally, despite expectations that the US Federal Reserve will raise its funds rate two or three times by end of this year.

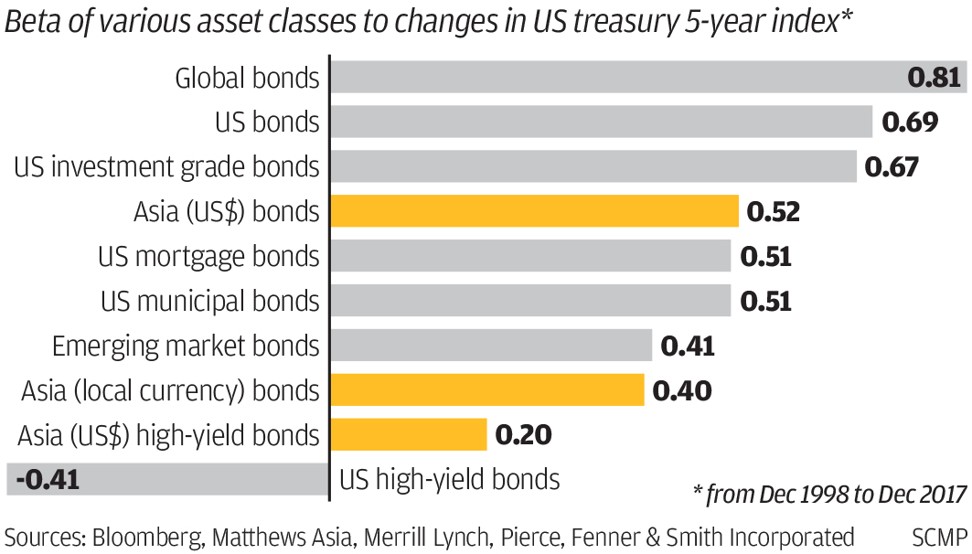

Teresa Kong, head of fixed income at Matthews Asia, who manages about US$150 million across strategies that invest in high-yield and investment-grade bonds, said Asian high-yield bonds tend to outperform investment-grade bonds because they have relatively low “beta” to US treasuries – how sensitive a bond’s price is to changes in the price of US treasuries. In this case, she picked the five-year US treasury index.

“A one percentage point move in five-year treasuries has historically translated to only a 0.2 percentage point move in Asian high-yield bonds; that compares with a 0.4-0.5 percentage point move in Asian investment-grade bonds,” she said, citing her team’s calculations based on the high-yield portion of the JPMorgan Asia Credit Index. Bond prices move inversely to market interest rates. Hence, the less sensitive a bond’s yield is to changes in US treasury yields, the better is its price performance. Asian credit is often priced based on US dollar interest rates.

High-yield bonds also have a smaller duration than investment-grade bonds, which is a measure of the bond price’s sensitivity to small changes in market interest rates. In Asia, Kong said, high-yield bonds tend to have a shorter average life of 4.3 years, compared with 7.6 years for investment-grade bonds.

Because the total return for a bond investment comes from the bond’s coupon payment and capital appreciation, which comes from an increase in the bond price – and as a higher duration indicates higher sensitivity to rates – many portfolio managers prefer to shorten the portfolio duration during a rate increase cycle by increasing their allocation to high-yield bonds.

Ken Hu, Invesco’s Asia-Pacific chief investment officer for fixed income, said he moved much of his portfolio to high-yield bonds in July 2017, after the Fed started raising interest rates and ended a seven-year period of near-zero policy rates in December 2015.

Hu said he saw attractive returns from Asian high-yield sovereign issues, particularly those that are part of the 68 countries covered by China’s Belt and Road Initiative. He cited sovereign issues from Mongolia and Kazakhstan in Asia, and Ghana and Kenya in Africa.

“Some of these high-yield sovereign bonds were issued at 7-8 per cent coupons. We prefer these high-yield sovereign issues because we believe their credit ratings could improve, now that China outbound investment into their commodity sector, infrastructure and mining will ultimately feed through to benefit these countries’ export sector, their productivity and, ultimately, improve their governments’ tax incomes,” said Hu, adding that this could lead to positive credit ratings for these sovereigns.

At the same time, however, he has also been hedging interest rate risks by cutting the duration of his bonds portfolio to zero. To achieve this, his team has been using interest rate derivatives, such as interest rate swaps and bond futures.

Jim Veneau, head of fixed income Asia at AXA IM, said while Asian high-yield bonds were less affected by the volatility in US treasury yields, this was true primarily for shorter duration corporate bonds of less than three years in maturity. Sovereign and longer duration companies have higher sensitivity in general to US treasury volatility.

Over the longer term, Asian high-yield performance will be driven mostly by the high coupons of the bonds, he said.

“As defaults have been generally low over a large part of the credit cycle, issuer credit spreads have tightened, causing the prices of the fixed and high coupon bonds to rise. Hence, Asian high-yield bonds have performed as a result of both income and capital appreciation, as credit losses from defaults have been relatively low,” he said.