After six months of record losses, can cryptocurrencies look forward to a hack-proof future?

The case for closer regulation of digital asset trading gains ground after losses of US$1.73 billion so far this year

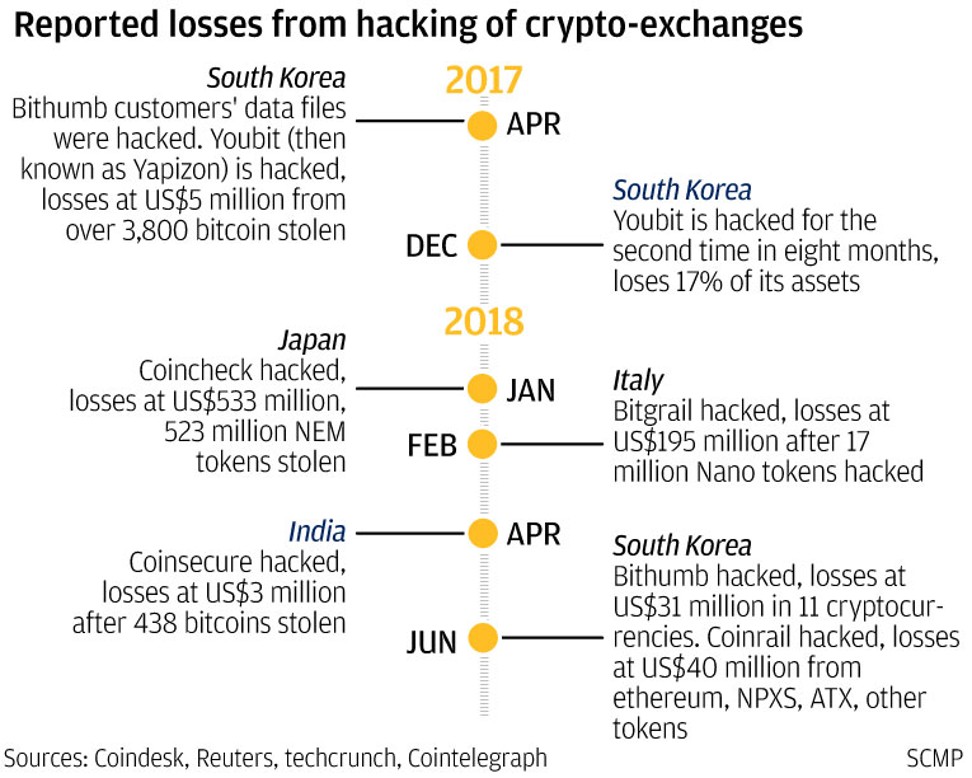

For the many cryptocurrency holders who care about security, the year 2018 is shaping up to be a nerve-racking one. The reported losses from cryptocurrency hacks and scams in the first half have already surpassed US$1.73 billion, or more than half of the total recorded losses since 2011, according to Crypto Aware, a community-focused advocacy initiative. Of these, 36 per cent represented losses from exchange hacking.

Cryptocurrencies are digital assets, and the exchanges are asset exchanges. All other exchanges that trade assets are regulated

The biggest exchange hack so far also took place this year. In January, more than 500 million units of the NEM token, then valued at US$547 million, were stolen from Japanese crypto-exchange Coincheck, upstaging the US$480 million loss suffered in 2014 by users of Mt. Gox, at that point the world’s biggest crypto-exchange, when 800,000 bitcoin were stolen. The hack triggered a series of legal claims and the crypto-exchange’s insolvency.

And even though Coincheck said in March it had refunded more than US$440 million to its customers using its own funds, the frequency at which exchanges are being hacked highlights an obvious question – does the current centralised exchange model, initiated by Mt. Gox and subsequently used by others, represent a security threat to digital assets?

Also, do alternative approaches, such as decentralised exchange platforms and crypto-custodian providers, represent safer ways to trade and hold digital assets, as many of them claim?

Trading IOUs rather than cryptocurrencies

Similar to traditional stock exchanges, a centralised crypto-exchange is run by an organisation that oversees its operations, maintenance and security, and grants users access to the trading platform for a fee. A centralised exchange connects buyers and sellers of cryptocurrencies, or cryptocurrencies to fiat money transactions.

And while blockchain is well known as the decentralised ledger technology that underpins various cryptocurrencies, ironically, today transactions involving these digital tokens on centralised exchanges often do not happen on blockchain.

So, despite blockchain being an immutable, tamper-proof architecture for recording data and transactions, because cryptocurrencies are being traded “off chain”, none of this data integrity benefits cryptocurrency traders.

Speed and costs are two key constraints for blockchain. Ethereum, for example, can only process about 20 transactions per second. Together with the transaction costs required for using the ethereum blockchain, this has meant many centralised exchanges today are instead using internal databases to process and record transactions.

“All the hacking that is happening on exchanges today, does not happen on blockchain. But because transaction records are updated on the exchange’s internal database, hackers can just move digital assets around by changing the names of whoever owns the asset,” said Lionello Lunesu, co-founder and chief technology officer at Enuma, a blockchain engineering company helping the Hong Kong-based OAX Foundation to build a decentralised exchange platform. This platform is expected to launch in 2019.

Also, in the actual trade the parties involved do not directly trade cryptocurrencies with one another, but trade IOUs, which represent tokens deposited with an exchange. This means the traders have surrendered custody of the cryptocurrency to the exchange, said Lunesu.

“Hence, depending on the terms and conditions of the exchange, and whether the exchange segregates clients’ assets, these factors can affect the legal rights of digital asset owners when it comes to claiming back their lost cryptocurrencies,” he said.

Amid all the security breaches suffered by centralised exchanges, increasingly, backers of decentralised exchanges such as OAX Foundation have emerged, arguing their platforms could enforce better protection for digital assets. OAX Foundation raised US$18.8 million from a token sale in June 2017 to develop the project.

Decentralised, ‘trustless’ trading

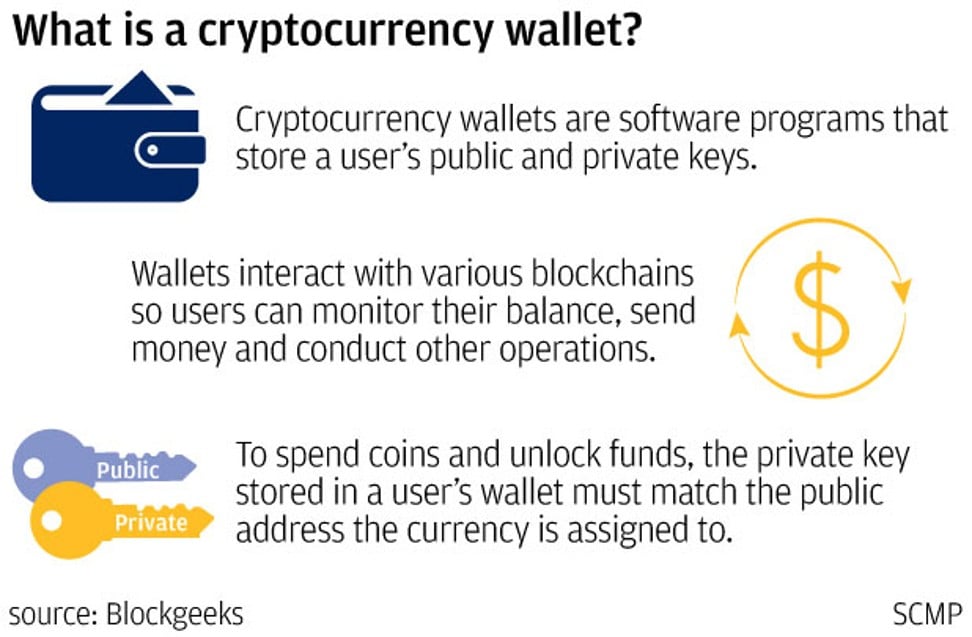

Lunesu said one key aspect of a decentralised exchange that could enhance security is that in a distributed network parties are trading with each other from their own wallets, instead of having to deposit all their cryptocurrencies in the wallets of one exchange – and attracting the attention of hackers.

“By requiring users to post ethereum deposits on the blockchain, we are moving the trust away from an exchange operator. In case there is a dispute with a transaction, then the aggrieved party can produce proof of what they are owed and the blockchain smart contract will adjudicate over the dispute,” he said.

Smart contracts, a technology embedded in the ethereum blockchain, are digital contracts that can be self-executed in accordance to the terms and conditions specified in the computer code. If the smart contract determines that, based on evidence, the conditions are satisfied that one party is owed a payment, then the blockchain will release the deposits to that party.

Because of the transaction speed constraints of blockchain, OAX plans to support trading between two parties over the internet without using blockchain, only allowing any party to revert to the blockchain smart contract for settling trade disputes.

By collateralising trades with deposits, it allows users to transact in ways similar to securities margin trading. Only in this case, no one except the trader will determine how much “leverage” they are willing to accept from the other party.

Need for a referee

But Terence Tsang, chief operating officer at Tidebit, which runs a centralised exchange in Hong Kong and Taiwan, said just like conventional securities trading, there are important roles an exchange operator plays that cannot be replaced by smart contracts.

“If you let the market run on its own, in case of fraudulent behaviour or someone flouting the rules, there will be no one to immediately step in to prevent a disorderly market. When you don’t have a central operator, it becomes a marketplace in which you cannot hold anyone accountable for misconduct,” he said.

When bitcoin first emerged in 2009, most trading took place through peer-to-peer networks, rather than in a centralised marketplace. But as transaction volumes have grown over the years, some in the trading community have come to appreciate the role a centralised exchange plays in overseeing and regulating trading activities, much like a referee who helps to deal with potentially dishonest behaviour.

Smart contracts are also not bulletproof. In fact, there have been many instances where they have been affected by bugs, and could be exploited for malicious purposes. Replacing an exchange operator with a smart contract could thus be risky, said Tsang.

At Tidebit, he said, as much as 95 per cent of client assets’ value is held in a “cold wallet”, or a storage device that allows for the keeping of digital assets offline. Following the hack at South Korean exchange Bithumb in June 2018, it said it had moved all users’ digital assets to a cold wallet. A “hot wallet” is connected online.

“Exchanges should not put all different hot wallets on a single server, but should put different cryptocurrencies across different servers to minimise the risk of hacking. We also have a wallet management system where only a small percentage of digital assets is stored on hot wallets, because this is for readily meeting clients’ withdrawal needs,” he said.

Grounds for regulation

Duncan Watt, a consultant with the financial services disputes and investigations team at law firm Eversheds Sutherland, said Hong Kong crypto-exchanges are not regulated by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority. And unless they are involved in the trading of securities or futures, these are not regulated by the Securities and Futures Commission as well.

“As a result, there is no supervisory oversight from financial services regulators on the exchanges, and no regulatory protection in place for investors in the event of an exchange being hacked, or becoming insolvent. This is just an aspect of the additional layer of risk that should be kept in mind by individuals engaging in crypto-asset trading,” said Watt.

In Japan, crypto-exchanges are required to register with the Financial Services Agency. After the record losses caused by the hacking of Coincheck, which had been operating as a quasi-operator while its registration was still under review, the FSA also tightened supervision. It has suspended operations at some domestic exchanges and ordered others to improve their security systems.

Tidebit’s Tsang said regulations such as registration or licensing requirements are needed for the healthy development of cryptocurrency trading.

“Cryptocurrencies are digital assets, and the exchanges are asset exchanges. All other exchanges that trade assets are regulated. If you have an exchange that is weak in risk control and compliance, it will easily fall prey to hacking and price manipulation,” he said.