Exclusive | ‘Made in China 2025’: how new technologies could help Beijing achieve its dream of becoming a semiconductor giant

The third instalment of a series on China’s hi-tech industry development master plan looks at semiconductors, and how the country’s rapid embrace of new technologies could help it close the gap with advanced makers

A year ago, Chinese government departments across the country received an order from the general office of the Communist Party to hand in a timeline detailing how soon they could replace existing computer hardware and software programmes with domestic substitutes.

Under the guise of ensuring information security, the central government’s intent was to reduce use of computers, servers, semiconductor chips and software made by Western firms, as it looked to build its own core technologies, lessen its dependency on imports and become a big player on the global tech stage.

“The US controls the most important core technologies,” said Roger Sheng, an analyst at research firm Gartner. “The standards are all in the hands of the US, which means it controls the upstream and downstream segments of the industry chain,” he said, referring to the entire process of making a chip, from design and manufacturing to consumption by end users.

“The first step is to see if they can compete with Korea and Taiwan, then slowly see if they can compete with the US. Competing with the US is not a one-day or two-day matter.”

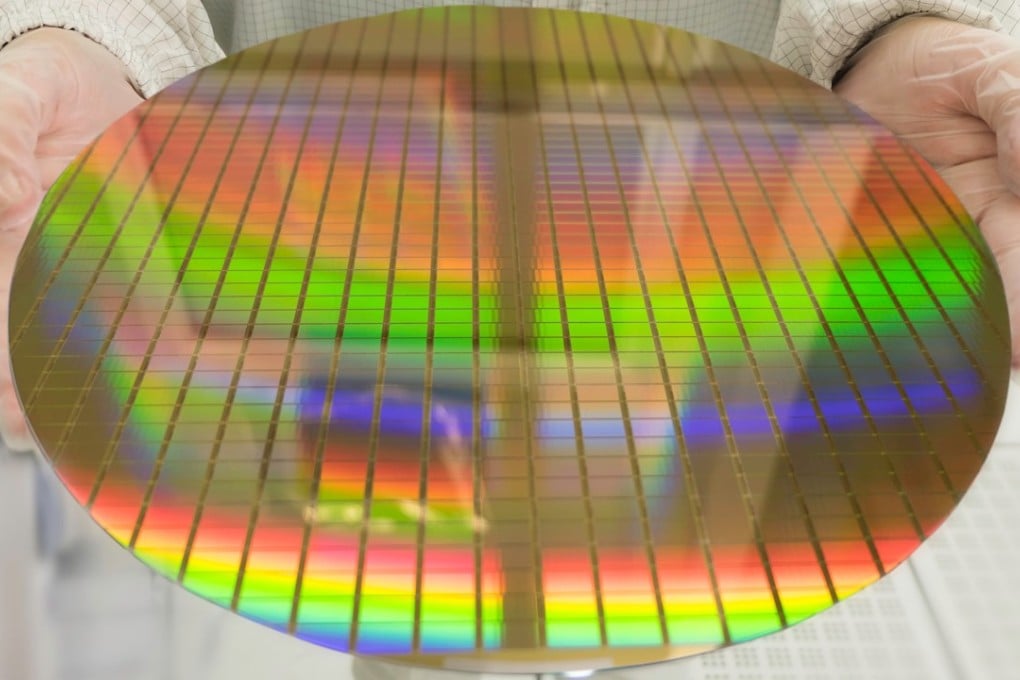

Mainland China’s huge manufacturing industry makes it the world’s biggest consumer of chips – the “brains” that power everything from electrical appliances and smartphones to the most sophisticated super computers and driverless cars.