Developers’ cosy ties with politics may explain Hong Kong’s biggest woe: widening income gap in the least affordable city on Earth

- In a series of in-depth articles on the unrest rocking Hong Kong, South China Morning Post goes behind the headlines to look at the underlying issues, current state of affairs, and where it is all heading

- In this latest instalment, the Post looks at the cosy ties between Hong Kong’s business elites and politics in the city and in Beijing

As Hong Kong’s unprecedented outbursts of civic unrest enter their 14th week, the link between business and politics – and its implication for the daily lives of the city’s 7.5 million residents – is coming under increasing scrutiny, while activists, policymakers and academics alike seek to explain the anger that seethes under one of Asia’s most prosperous urban centres.

The roots of Hong Kong’s entangled ties between business and politics can be traced to the city’s colonial history, when hometown business elites were also local community leaders, endorsed and endowed by administrators with influence and leadership roles.

In the city’s first post-colonial administration after 1997, businessmen made up eight of the 11 non-official members of Tung Chee-hwa’s cabinet. The ratio was little changed at 70 per cent under Tung’s successor Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, falling to half during Leung Chun-ying’s term from 2012 to 2017.

The ties between business and politics extend all the way to Beijing.

When Chinese officials took over Hong Kong from the British colonial government in 1997, they kept wooing the city’s biggest hongs, banks and conglomerates to show that the ‘one country, two systems’ formula of a capitalist market economy within China’s socialism could work, said Lau Siu-kai, vice-president of The Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies, a semi-official think tank.

“Beijing assured them the safety of their investments, and allowed them bigger political influence to stabilise the [environment to increase investors’ confidence],” Lau said.

Hong Kong mulls over emergency law to quell protests

Three generations of Fok men sat on the Chinese legislature’s advisory body. Fok himself had a seat in the legislature, the National People’s Congress, and was a member of the drafting committee for Hong Kong’s Basic Law, as the city’s mini constitution is known. His eldest son Timothy Fok Tsun-ting was a delegate in the 11th and 12th CPPCC from 2008 to 2018, while eldest grandson Kenneth Fok Kai-kong is a delegate in the current 13th CPPCC that serves from 2018 to 2023.

“Beijing issued strict guidelines about the meeting in recent years, but enforcement began this year,” said CPPCC delegate Christopher Cheung Wah-fung, a lawmaker representing Hong Kong’s financial services industry. “We are required to arrive before meetings start and are not allowed to leave during the proceedings. Any delegate who could not attend has to explain his or her absence. We are expected to attend even the lunches and dinners during the conference period.”

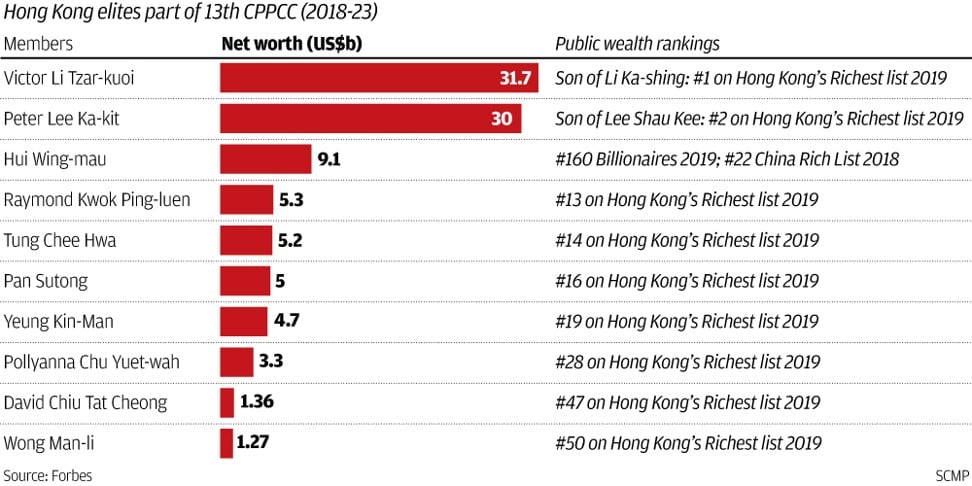

As the ranks of Hongkongers grew over the years in the CPPCC, tripling to 156 in the current term, so did the representation of tycoons and business elites. Ten of the current delegates hail from the city’s wealthiest families on Forbes’ Hong Kong Richest 2019 list.

Is China using protests to chip away at Hong Kong’s economic freedoms?

A consequence of the growing influence of billionaires is the widening income gap in Hong Kong and a further concentration of wealth in the hands of the few, said Lau.

The growing ranks of billionaires in Hong Kong’s CPPCC delegation underscore their outsize influence in the city’s economy.

Prices of lived-in homes drop for second month amid protests, trade war

The concentration of wealth and political power has not gone unnoticed, or been without controversies, deepening the schism between the haves and the have-nots in Hong Kong.

Built on 26 hectares of land in Pok Fu Lam on the south side of Hong Kong Island, the project comprised four office towers and a five-star hotel that took up two-thirds of the land area, while the remaining one third yielded 4.39 million square feet of oceanfront residential real estate.

The entire project was awarded in 1999 to Richard Li’s Pacific Century Group without an open tender.

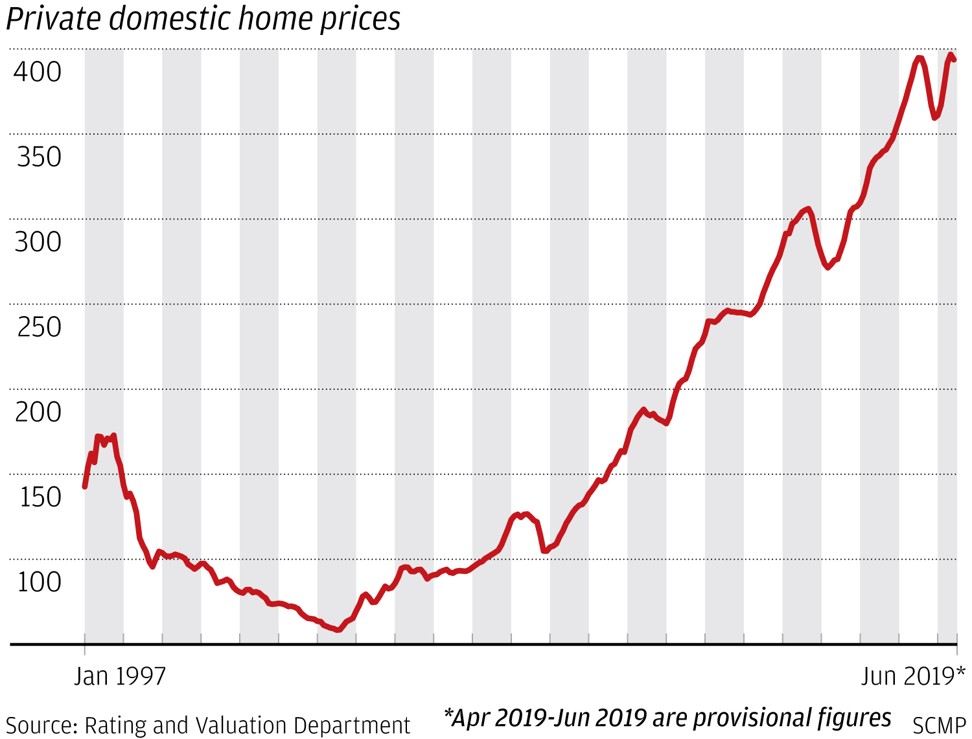

The career civil servant – he coined the phrase “caring capitalism” while he was the city’s Financial Secretary in 1996 – suspended the construction and sale of Home Ownership Scheme flats to arrest an unprecedented decline in real estate prices, and replaced land auctions with a closed tender system.

The result of the policies was a 57 per cent plunge in the city’s annual housing supply from 59,800 units in 2006 to 25,700 homes by 2016, comprising private, subsidised and public rental apartments. The shortage caused home prices to soar over a decade, laying the ground for a property bull run that continued until the end of 2018.

At the depth of the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis, HK$3 million (US$382,400) fetched a flat measuring 686 square feet (64 square metres) on average, according to Midland Realty. Two decades later in 2018, the living space had shrank to 200 sq ft for the same price, while rents have soared 200 per cent.

Dismal living conditions and a yawning income gap have led to a groundswell of simmering anger, akin to a tinderbox awaiting a spark.

What began on June 9 as a peaceful march by an estimated 1 million people to protest against a controversial extradition bill has since deteriorated into 12 weeks of frequent clashes between police and protesters.

The concentration of wealth and influence is also creating an uneven playing field for Hong Kong’s mid-size developers, forcing them to look elsewhere for growth as they are squeezed out by cash-rich rivals.

“Hong Kong land is too expensive,” said Chris Hoong, managing director of Far East Consortium, a minnow with HK$8.4 billion in value, a 10th of the average capitalisation among Hong Kong’s bigger publicly traded developers.

Expensive housing costs also spill over into higher salaries for the workforce. Rents make up a third of the total costs of Hong Kong’s small enterprises, which account for 98 per cent of the city’s commercial life, while wages make up another one third, Chau said.

The cosiness between Hong Kong’s business elites and Chinese politics has shifted subtly since Xi Jinping ascended to China’s highest office in 2012.

Those private meetings have ceased since Xi came to power. China’s leaders nowadays were holding fewer meetings with Hong Kong tycoons when they visited the city to avoid potential criticism that they were focusing only on rich people, analysts said.

Sino Land chairman urges end to protests hurting city’s economy

The family diversified its sprawling businesses, which touch virtually every aspect of a Hongkonger’s daily life from CK Asset’s property to two of the city’s four mobile phone networks to shopping at AS Watsons retail shops or Park’N’Shop supermarkets, and oil and imported containers handled by CK Hutchison’s ports.

Europe now contributes 55 per cent to CK Hutchison’s first-half earnings, while Hong Kong makes up a mere 3 per cent, and mainland China accounts for 10 per cent.

Change had also been afoot in Hong Kong. The incumbent Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, who unleashed the worst political crisis in Hong Kong’s history with her controversial extradition bill, appointed the fewest businessmen to her cabinet in two decades, with just seven of 16 non-official members, or 43 per cent, from the corporate sector.

Still, the question amid all the unprecedented public unrest is how Beijing or the city government can ease the tension, bridge the social divide and narrow wealth disparity when conflicts had been deepened.

“Have you seen any proposal by any of the tycoons [on the CPPCC delegation] to eliminate the conflicts between Hong Kong and mainland China?” asked Chung Kim-wah, an assistant professor at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University’s Department of Applied Social Sciences. “Have you seen them speak out before the issues got any worse?”

They included the biggest local developers SHKP, CK Asset, Henderson Land, New World Development, Sino Land and Swire Properties. Notably absent from the list was Chinese Estate, controlled by fugitive tycoon Joseph Lau Luen-hung, who earlier sought a legal challenge against Hong Kong’s extradition bill, but eventually dropped it.

The statements were “cookie-cutter” messages, an example of the token gesture to “echo Beijing’s directive and thinking” instead of “leading any reflection on the issues at stake for Hong Kong,” Chung said.

Still, 13 weeks of street protests cannot untangle the Gordian knot of entrenched business interest and politics built over decades, which led Hong Kong to where it is, analysts said.

“This is not going to fade away, and it will always be like that,” said Joseph Tsang, chairman of JLL Hong Kong, adding that the phenomenon of greater wealth disparity triggering social unrest “will not improve in short term” as the big players have firmly controlled the city’s businesses.

Additional reporting by Sandy Li, Martin Choi and Enoch Yiu

Other articles in this series have analysed Hong Kong’s emergency law, whether protests will ruin the city’s role in the Greater Bay Area plan, Taiwan’s high stakes in the protests, how leaders have spurned the chance to listen to public opinion, and how Beijing keeps getting Hong Kong wrong