Singapore’s ‘stingy nanny’ abates and outshines Hong Kong with rental relief to ease retail pain during coronavirus pandemic

- Singapore has unveiled almost S$60 billion (US$42 billion) of stimulus amid worsening pandemic fallout, larger than Hong Kong’s measures

- The city’s biggest landlords, some of which are controlled or influenced by state investment arm, have quickly passed on the benefits to retailers

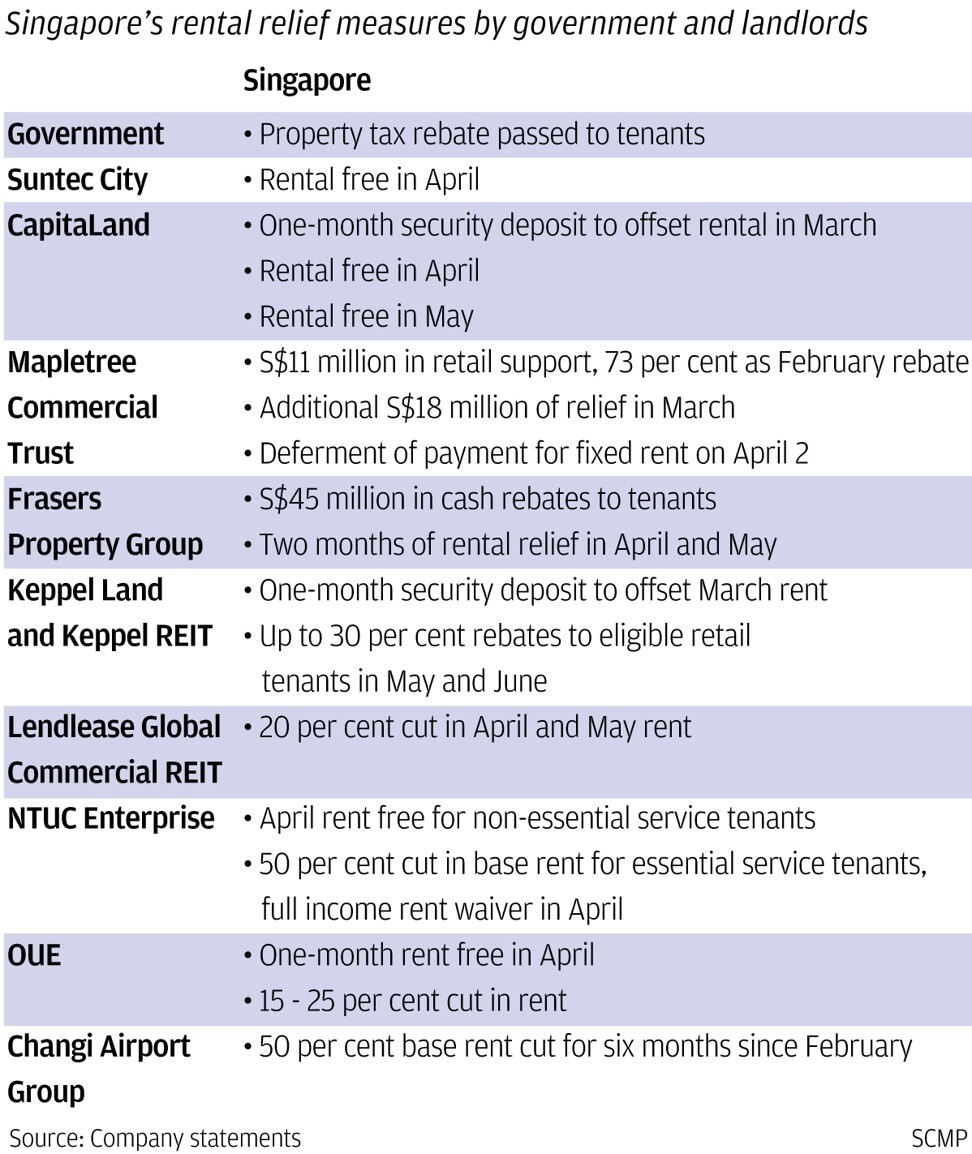

“The landlords in Singapore have been more understanding and the government has been giving out subsidies, including property tax rebates, which they can pass to tenants,” said Nelly Ngadiman, managing director for Southeast Asia at Bluebell. “We have seen a slowdown in sales since February, a bit later than Hong Kong.”

The swift response is a stark contrast to Hong Kong, where landlords have offered what the industry calls “slow-drip” concessions to retailers even as sales cratered under months of social unrest, long before the pandemic pushed Hong Kong to unveil its record HK$137.5 billion (US$17.7 billion) relief package.

While no two programmes are similar, the level and readiness of policy support could shape impressions and decisions among investors long after the current public health crisis is over. Both financial hubs compete for everything from initial stock offerings to talents and billionaires.

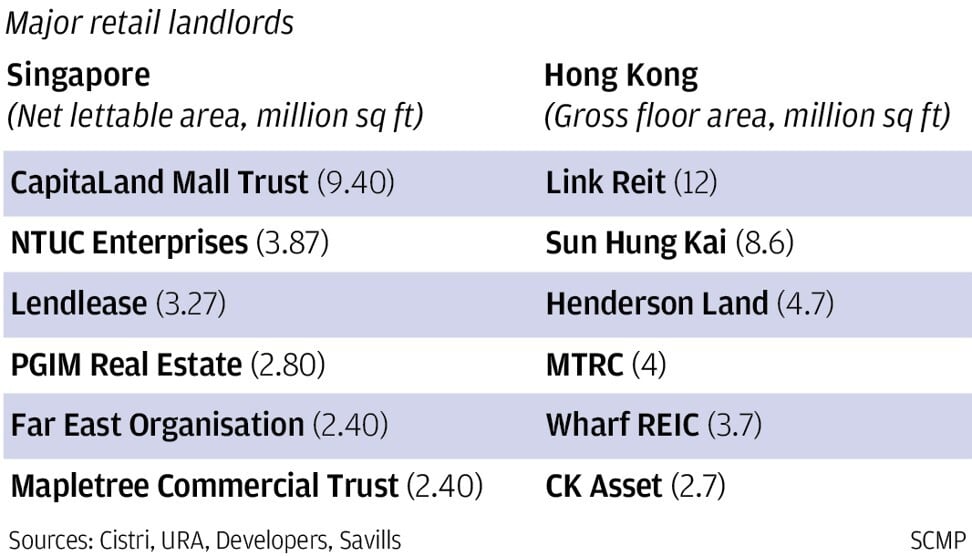

These days, the government through its state investment arm owns equity stakes in some of the city’s biggest landlords, notably its 51.5 per cent holding in CapitaLand, and 32.9 per cent stake in Mapletree Commercial Trust, according to Bloomberg data.

Maggie Hu, assistant professor of real estate and finance at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said it boils down to ownership structure and relative affordability factor.

“Singapore landlords offer more generous rent concessions partly because the move is pushed by the government,” she said. “It is related to the fact that most of the big developers there are government controlled or influenced.”

“The level of support today is far from sufficient for retailers to survive” despite the government’s appeals to the landlords, Redjeb said. Most of the concessions are on base rental, on a monthly review basis, and extracted “through very tense negotiations,” he added.

Stewart Leung, chairman of the executive committee at Hong Kong Real Estate Developers Association, the powerful guild for one of the pillars of the city’s economy, came to the defence for the government and the big developers.

“Singapore is a country, it can immediately do what it needs to do by issuing an order,” Leung said. As a special administrative region of China, “sometimes it is not possible to take big actions in Hong Kong, which will draw a lot of different voices,” he said.

Even as the coronavirus pandemic has hastened the slump in retail sales across the Asia-Pacific region over the past 12 months, the damage has been uneven.

Hong Kong’s February retail sales slumped by a record 44 per cent, as an escalating coronavirus outbreak in mainland China kept mainland Chinese tourists away from Hong Kong, casting a pall on the annual shopping festival during the Lunar New Year holiday.

In Singapore, retail sales slid by 8.9 per cent, the steepest in 12 years. In February, tourist arrivals crashed 94 per cent in Hong Kong, shrinking by a more moderate 57 per cent in Singapore.

Under the plan of Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, the Hong Kong government would pay 50 per cent of workers’ salaries for six months, subject to a cap, to protect 1.5 million jobs, among others.

A handful of government-backed landlords have come to its aid. Link Reit, which acquired most of its properties from the Housing Authority, expanded its tenant relief plan to HK$300 million from HK$80 million. MTR Corporation has extended its half-rent incentive for small to medium sized tenants to April.

Even so, Hong Kong’s private developers have not gone the full distance of waiving rents for retail tenants. Sun Hung Kai Properties, for example, would “closely monitor” the impact in April before deciding on any relevant relief measures.

The developer, the city’s largest mall owner under Asia’s third richest Kwok family, lowered retail base rent by 30 to 50 per cent on a case-by-case basis in February and other undisclosed relief in March.

Singapore’s bag of goodies included a waiver on property tax this year, benefiting owners of more than 58,000 qualifying retail and food-and-drink properties, and a rent-free April for most retailers. The state will also subsidise 75 per cent of employees' wages this month for companies in all sectors of the economy.

The law ministry on April 7 introduced a bill to let businesses and individuals defer certain contractual obligations such as rent and loans, for a certain duration. Under the proposed law, landlords would not be allowed to kick out their tenants, or repossess the premises.

The new law “flips the balance of power towards tenants, and that has helped,” said Loh Lik Peng, founder of Unlisted Collection of restaurants in Singapore.

Still, Singapore’s example “is an exception,” said Kevin Tsui, associate professor of economics at Clemson University in South Carolina. Even New York, facing worse pandemic conditions, has not taken that legal route, he added.

The coronavirus pandemic has infected more than 2.1 million people globally, and killed at least 145,000 people through April 17.

With a nationwide election due by April next year, the government of Singapore is keen to prevent a deeper economic slump to appease its citizens. Its projected 1 to 4 per cent contraction this year would be the worst since at least 2001, according to Bloomberg data.

Coronavirus and Singapore elections: the best or the worst of times?

Derek Tan, head of Singapore property research at DBS Group Holdings, said Singapore landlords are more generous than their peers in Hong Kong because their strategy is to retain tenants. Replacing departing tenants would be very difficult in a market downturn.

“Landlords have realised the tough situation, that if you do not offer more [rent reduction], you will just lose the tenants,” he said. “They will be under a high risk of having no tenant and no cash flow.”

Tan also noted that Singapore landlords have “more financial flexibility” because they did not suffer from the impact of anti-government protests. Their peers in Hong Kong might offer more rebates if the Hong Kong government also shuts down the malls, he added.

That remains to be seen. Among Hong Kong restaurant operators, the verdict is clear. With rents eating up 30 per cent of revenue, 99 per cent of them decried the support from the government as insufficient, according to a survey by Save Hong Kong F&B, a coalition of 600 restaurants with more than 10,000 workforce in the catering industry.

“Unfortunately, landlords think they rule Hong Kong, not the Chief Executive,” Alan Lo, co-founder of restaurant operator Classified Group, said during a webinar this week. “Frustration in the retail and F&B business is reaching a breaking point, where people are ready to just give the keys back to the landlord.”

The Swatch Group, the world's biggest watchmaker by sales, believes Singapore landlords are more attuned to the fallout in the retail industry.

“There are some landlords who are very empathetic, cooperative, and understand the situation, and there are some greedy landlords,” a spokeswoman in Hong Kong said. “Singapore is more cooperative, also driven by the local government. Hong Kong is just the contrary.”

(With additional reporting by Ryan Swift and Liu Yujing in Hong Kong)