China looks to carbon capture and hydrogen to push aviation, shipping, power plants, heavy industries towards 2060 target

- Nine of every 10 vehicles on China’s roads will have to run on non-fossil fuels, while half of aircraft will fly on green hydrogen to put China on track to cutting carbon emissions by 75 to 85 per cent, leaving the residual amount to be offset by removals

- 90 per cent of heavy industries will need to be retrofitted with carbon capture facilities

The fourth part of a series on China’s carbon neutrality goal examines the heavy lifting that must be done by the country’s biggest carbon dioxide emitters to reach that target by 2060. Earlier instalments of the series are here, here and here.

Nine of every 10 vehicles on China’s roads will have to run on non-fossil fuel, while half of the aircraft fly on green hydrogen and 90 per cent of heavy industries will need to be retrofitted with carbon capture facilities to put the nation on track to cut carbon emission by 75 to 85 per cent, leaving the residual amount to be offset by removals, according to the Boston Consulting Group (BCG).

“Some of the technologies required, such as carbon capture and storage and [emission-free] hydrogen fuel are not [commercially] ready yet,” said Thomas Palme, who leads BCG’s social impact practice in China, adding that it can only be possible “with concerted effort and investment.”

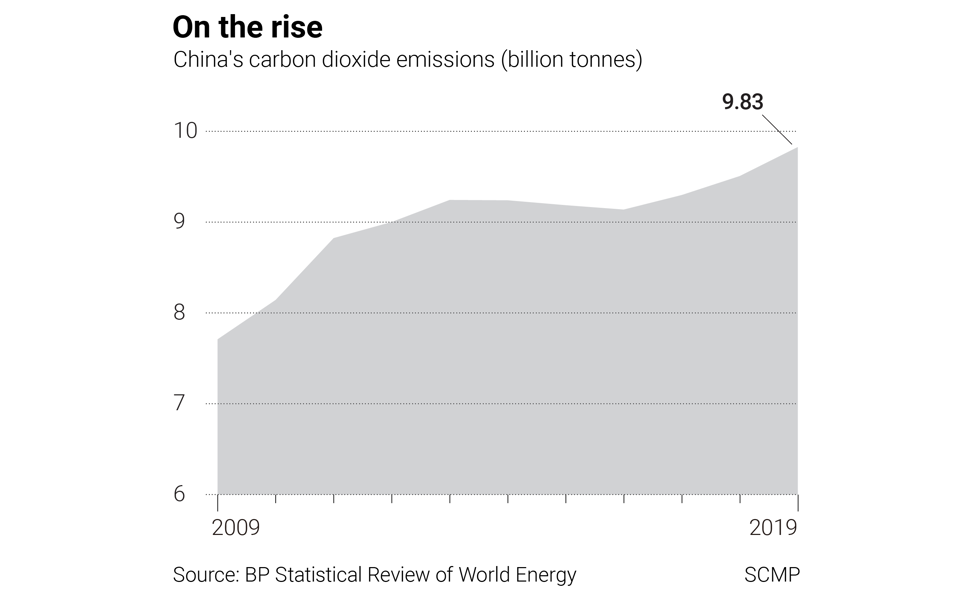

China’s coal and gas-fired power plants are responsible for almost half of the nation’s carbon dioxide emission, while heavy industries – including the world’s largest capacity for steel, aluminium, petrochemicals and cement – contribute one-third, BCG said.

With an average age of less than 13 years – out of a typical useful lifespan of 40 years – the use of some power plants could be extended even as climate policies clamp down on emissions.

This is particularly important since 60 per cent of the world’s coal-fired plants could still be operating in 2050, as could 40 per cent of steel mills – mostly in China – unless they retire early, according to International Energy Agency (IEA) in Paris. That is not viable, as the cost of installing carbon capture facilities would triple the price of coal-fired power, said HSBC’s head of Asia utilities research Evan Li, citing data by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis in Ohio.

The prospect of shutting down mass coal-fired power plants could present a policy dilemma between climate change and economic stability. China’s banks could see their default ratio on loans to the coal-fired power sector surge from 3 per cent to over 20 per cent within a decade, according to a scenario analysis by Centre for Green Finance Development, Tsinghua National Institute of Financial Research.

This would avoid bankruptcies that spill over to bad loans and social risks, he said, adding that talks are ongoing in Shanxi, China’s largest coal producing region, to facilitate such bonds.

Carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) – the capture of carbon dioxide from the emission source, or directly from the atmosphere – has been in use for 45 years, according to the consultancy Global CCS Institute in Melbourne. In the United States, large-scale CCUS projects involve injecting carbon dioxide into oil wells to enhance output.

The technology has been tested in China for about a decade, pioneered by coal mining giant Shenhua Group, now renamed as China Energy Investment Corporation. Carbon dioxide collected from coal-to-oil conversion projects in Inner Mongolia is trucked and injected into sealed underground caverns for permanent storage.

PetroChina has also been collecting carbon dioxide from a natural gas processing plant and injecting it into its Jilin oilfield since 2018.

Retrofitting CCUS will have a greater chance of success for power plants and industrial facilities that are young, efficient and located near places with opportunities to store or use carbon dioxide, IEA said. When CCUS can be commercially viable in China is unclear, as details of the national mandatory carbon dioxide emission quota – critical for putting a market price on emissions – have not been announced.

“China has some successful CCUS pilots, but their applications have been rather restricted, the volumes rather limited and [they are] commercially uncompetitive,” said Yang Fuqiang, China programme senior adviser on climate and energy, at The Natural Resources Defence Council in New York.

China must shut coal plants to meet Xi carbon-neutrality goal: US think tank

The technology must be deployed in large scale to reach carbon neutrality, IEA said.

“Reaching net zero [carbon emission] will be virtually impossible without CCUS,” IEA said in September. “Alongside electrification, hydrogen and sustainable bioenergy, CCUS will need to play a major role.”

CCUS may be ready for industrial application by 2030 in China, with a cost reduction of between 40 per cent and 50 per cent by 2040, according to a technology development road map by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) last year.

“Hurdles to faster CCUS deployment in China include the lack of a legal and policy framework, limited market stimulus and inadequate subsidies,” the IEA said. “Public understanding and awareness is relatively low.”

“Green” hydrogen, the other key technology for fighting climate change, has made significant progress towards commercial deployment due to a drastic fall in renewable energy cost. Production of this virtually emission-free fuel involves using renewable electricity to split water into oxygen and hydrogen.

The world’s first wind-generated green hydrogen power project, scheduled for commission in January, may be expanded into a large plant for deployment around 2025, according to Siemens Gamesa, the dominant European turbines producer.

Hydrogen and ammonia are touted as the mainstay clean fuel to replace coal, diesel, petrol, bunker and jet fuel in a few decades, with potential applications in heavy industries such as iron and steel, chemicals and glass.

“The pathway to emission-free electricity is wind and solar, and the pathway to emission-free everything else is green hydrogen produced from wind and solar,” said Alex Tancock, co-founder and managing director of InterContinental Energy, one of the growing list of developers pushing for hydrogen projects.

A consortium led by InterContinental proposed a US$36 billion solar and wind-powered hydrogen production project aimed at East Asia. Located in the Pilbara Desert in Western Australia state on a site six times the size of Hong Kong, it comprises 26 gigawatts of wind and solar farms, 2.3 times Hong Kong’s power generating capacity.

The consortium is in talks with Asian buyers of hydrogen and ammonia, including power and shipping firms, besides technology, energy, and asset management companies for investments by 2025 for construction to start.

Global hydrogen production could surge sevenfold by 2070 from last year’s 75 million tonnes, IEA said.

Direct use of hydrogen by ships and vehicles may take up 30 per cent of demand in 2070, while synthetic aircraft fuel will account for 20 per cent. Liquid hydrogen can be used for short-haul flights, while synthetic fuel can be used in existing jet engines, Tancock said.

Airbus revealed three concepts in September for the world’s first zero-emission commercial aircraft, with modified gas turbine engines that use hydrogen instead of jet fuel, which could enter service by 2035.

Transport accounted for 9 per cent of China’s estimated carbon emission of 11.7 billion tonnes last year, BCG said.

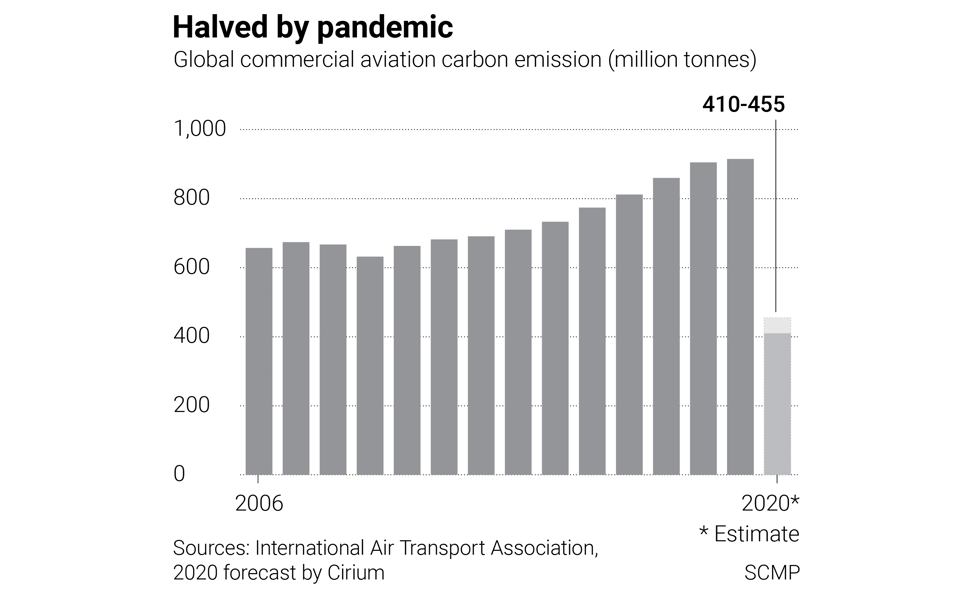

Commercial aviation accounts for 2 to 3 per cent of global carbon emission, according to the International Air Travel Association (Iata), the industry guild. It has committed to cap members’ carbon emissions this year, and halve them by 2050 from 2005 levels.

China has included domestic aviation among eight sectors to be subjected to carbon emission caps and quotas trading.

Domestic flights grew 7.5 per cent to 83 billion tonne-kilometre last year, while the entire industry’s carbon emission per tonne-km fell 16 per cent from 2005, according to the Civil Aviation Administration of China. Some 74.5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emission could potentially be subject to a cap-and-trade regime.

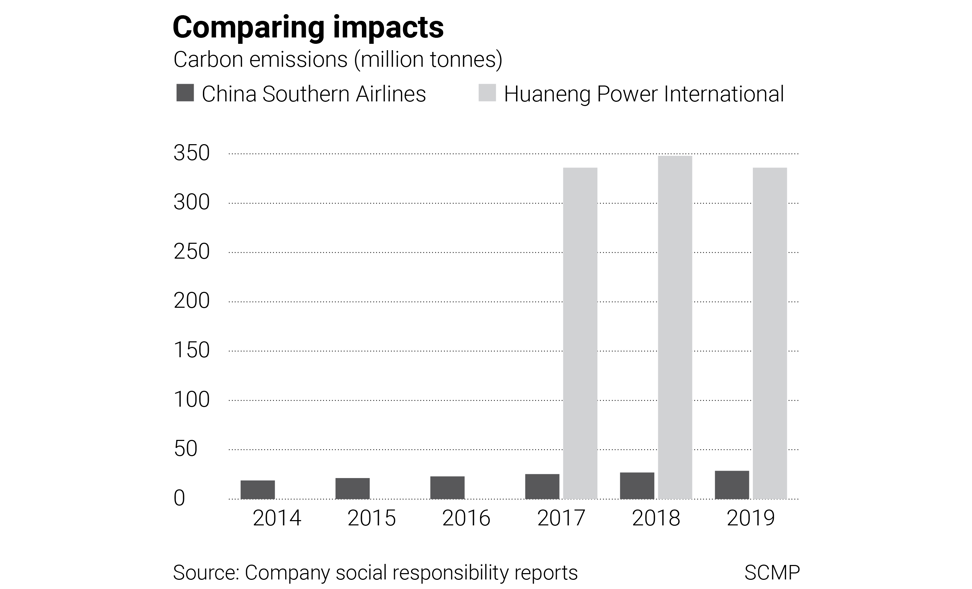

China Southern Airlines, the nation’s largest fleet operator, said its 2019 carbon emission grew 6.4 per cent to 28.6 million tonnes. The Guangzhou-based carrier tested a 10 per cent blended bio-jet fuel made with sugar cane in a flight last year, emitting 73 per cent less carbon dioxide than conventional jet kerosene.

The shipping industry is also looking to hydrogen, although huge research and development investments will be needed before this can become commercially viable, according to London-based International Chamber of Shipping.

“After a long history of wind, coal and oil-fuelled ships, a fourth propulsion revolution is needed if shipping is to decarbonise completely … an entirely new generation of fuels and propulsion systems will need to be developed,” it said in a report last month.

The task facing the industry is daunting. Long-term growth in maritime trade means even if the average carbon emission by the entire global fleet is slashed by 90 per cent, it would only cut the industry’s carbon emission by half by 2050, the chamber said. The global vessel fleet – consuming 4 per cent of oil output and contributing 2 per cent in carbon dioxide emissions – must be retrofitted, while new fuel supply networks must be developed if hydrogen and ammonia are to be adopted, it added.

The shipping industry proposed a levy on marine fuel sales to provide US$5 billion over 10 years for research to turn the “propulsion revolution” into reality, the chamber said.

For InterContinental, exporting ammonia to China is more viable, due to the high costs needed to ship hydrogen at minus 253 degrees Celsius, if the project takes off.

“I would expect China to have a big industry producing hydrogen, unlike Japan and South Korea which have little resources and would have to import,” Tancock said. “Projects like ours will supplement China’s production by providing lower-cost green alternatives like green ammonia.”

Additional reporting by Iris Ouyang and Echo Xie