Hong Kong’s housing crisis: how much of the blame for homes crunch lies with city’s property developers?

- In a city facing a housing crisis where demand hugely outstrips supply, more than 4,000 completed flats remain unsold in Tai Po

- Situation has led some to accuse developers of hoarding unsold flats while biding their time for prices to rise

In the last of a three-part series on Hong Kong’s housing crisis, the Post looks at the city’s property developers and their role in the dire situation. Read part one here and part two here.

Thousands of new high-rise homes have come on the market over the past two years in Tai Po, in the eastern corner of Hong Kong’s New Territories facing Tolo Harbour.

In a city facing a housing crisis where demand far outstrips supply, a large number of completed flats have remained unsold in Pak Shek Kok, near the Hong Kong Science Park.

One in three homes is not yet sold at Centra Horizon II, a complex of 1,408 flats in 12 tower blocks built by Billion Development & Project Management and completed in the middle of last year. The flats have been vacant for a year.

A five-minute walk away, The Ontolo is only three-quarters sold. Developer Great Eagle Holdings has managed to move 540 of the 723 flats since the project’s completion in the middle of last year.

Both developers have been selling homes to walk-in buyers through this year.

10:08

Hong Kong has until 2049 to fix its housing crisis, but is it possible?

Unsold units in Pak Shek Kok are among 4,372 completed flats in Tai Po that remain unsold, according to official data. That is 11.2 per cent of the total, the highest proportion of vacancies in new and existing projects across Hong Kong.

‘It’s sad for Hongkongers’: why many can’t afford their own homes

“Developers in the area have recouped their investments since their sales launches in 2019, so they are not in any hurry to sell since prices have been rising by between 20 and 30 per cent,” said Sammy Po, chief executive of Midland Realty’s residential department.

The situation has led some to accuse developers of hoarding unsold flats while biding their time for prices to rise.

“In a housing market already facing more demand than supply, the hoarding of completed flats aggravates the shortage and helps to push up prices,” said Alvin Cheung Chi-wan, associate director at Prudential Brokerage, an asset management, research and analysis firm.

After lawmakers shelved the plan, saying there was not enough time to scrutinise the proposal, some developers slowed down releasing their unsold flats.

“Developers would have been forced to speed up the sales of completed homes if the vacancy tax was enforced as planned. Releasing between 6,000 and 7,000 flats would have helped to ease the tight supply to some extent,” Cheung said.

Billion Development’s sales and marketing director Anthony Poon declined to comment on Centra Horizon’s sales or the vacancy tax. Great Eagle declined to comment.

The number of unsold new homes in Hong Kong has risen even as prices surged to a two-year high in June, hovering just 0.6 per cent below the previous peak in May 2019.

The total number of completed unsold new homes rose to 12,000 in June, up from 11,000 a year earlier and 10,000 in June 2019, according to data provided by the Transport and Housing Bureau.

Last year, Hong Kong had a total of 52,366 empty flats, or 4.3 per cent of the total, up from 3.7 per cent a year earlier, according to official data.

Developers moved to do more

Beijing’s directive puts pressure on the authorities to find the land needed to build the homes Hong Kong is so short of.

The city’s developers will be expected to do their part too, although in the past they have been blamed in part for the housing shortage and especially the skyrocketing prices of private homes.

State media criticised the city’s property tycoons for hoarding land, not developing sites to help meet the housing shortage and protecting their vested interests. They also encouraged the Hong Kong authorities to seize large swathes of unused land in the New Territories for public housing,

Since they were shamed in 2019, developers have become more responsive to the government’s call to help tackle the land shortage issue.

Some supported a transitional housing scheme, leasing their sites to charities to build temporary homes for low-income families in the long queue for public flats. SHKP, Henderson Land Development and New World Development are among those that have handed out large parcels for the initiative.

City leader Lam also appealed to developers to bear their “social responsibility” by sharing some of their land reserves to build public housing.

Under a land-sharing scheme she announced in October 2019, developers were invited to open up their agricultural land for housing projects.

Officials would allow a higher development density on the sites and, in return, the developers would surrender 70 per cent of the additional floor space for public housing.

Last week, SHKP, Henderson and Wheelock Properties also submitted plans to share their lots. If approved, the projects will yield more than 16,000 flats, nearly 40 per cent of Hong Kong’s annual supply target.

The developers’ increasing participation in the government’s housing efforts also comes against the backdrop of their dwindling influence in the Election Committee, the body that in the past was tasked with selecting the city leader.

Hong Kong’s housing crisis long blamed on land shortage, but are other factors at play?

With the changes, Hong Kong’s property tycoons will have less sway over the committee. In the past, their conglomerates, covering multiple sectors ranging from retail, shipping and real estate to transport and telecommunications, had as many as 300 direct and indirect representatives on the committee.

In the new framework, the commercial and industrial sector controlled by the tycoons will lose 15 seats to a new subsector for small and medium-sized enterprises. Their influence will be further diluted by the addition of 110 seats affiliated to national organisations.

‘Red tape causing delays’

Insisting they did not deserve the blame heaped on them since 2019, some developers pointed instead to government red tape and stifling urban planning rules as the reasons for delays that had contributed to the housing shortage.

Chinachem Group chief executive Donald Choi said the public had the incorrect perception that developers were behind the shortage of homes.

“Most developers want to find buyers for their projects,” he said. “We want to improve the living environment in Hong Kong, the same as the government, and in the public’s interest.”

Developers said a stark example of red tape getting in the way of the best plans could be seen at Kwu Tung, near Fanling public golf course, and Hung Shui Kiu, both earmarked as new development areas in the New Territories.

After authorities announced in 2007 that homes would be built, they took 10 years to complete studies, planning and public consultations before proceeding.

The first residents are only expected to move into the area’s new private housing in 2023 or 2024, almost two decades after the plan was first unveiled.

SHKP executive director Adam Kwok Kai-fai told the Post: “Not only does the planning study process need to be reviewed and compressed, the current planning policy should also be revisited, as it just freezes private development applications while planning studies are under way.”

He said there have been many cases of developers that were prepared to move forward with plans for “ready and sizeable private development sites” but were forced to wait years for government planning studies to be done.

Cutting red tape would “go a long way towards completing the puzzle earlier for the benefit of Hong Kong”, said the third-generation scion of the Kwok family, which controls SHKP, developer of nearly a quarter of all private-sector homes in the city over the past five years.

He pointed out that two common hurdles to creating a new town were the lack of road access and an MTR station.

If technical issues made it impossible to complete the rail work sooner, Kwok suggested allowing the private sector to take part in infrastructure development.

Indicating how developers had helped in previous new town developments, he said: “There were numerous successful housing projects completed before a nearby MTR station was operational. They all relied on alternative transport methods using shuttle buses, franchise buses or vans, with a transport interchange [built by developers] sometimes housed within the estate.”

Bidding frenzy in New Territories

The mismatch between housing demand and supply has sent developers competing for land even in areas of the New Territories that lack amenities or public transport infrastructure.

A large residential site in Kwu Tung North was sold by the government in April to SHKP for HK$8.614 billion (US$1.11 billion), or HK$7,184 per square foot, about 40 per cent above the market valuation.

Two months later, Wing Tai Properties paid HK$2.62 billion – or HK$9,208 per square foot – for a site near Sheung Shui railway station, also in Kwu Tung.

Since then, land prices in terms of per square footage have shot up 28 per cent in the area.

The bidding frenzy has refocused attention on the New Territories, which makes up 86 per cent of Hong Kong’s total area but currently holds only half its population.

Developers said there was land suitable for housing in the New Territories, in places such as Yuen Long, Fanling and Sheung Shui, and urged the government to take urgent steps to release it.

“Land prices increase quickly and sharply,” Chinachem’s Choi said. “The government needs to catch up with land creation that has lagged behind demand over the past decade.”

Chinachem and SHKP have proposed that unoccupied farmland should be converted at a quicker pace for residential development.

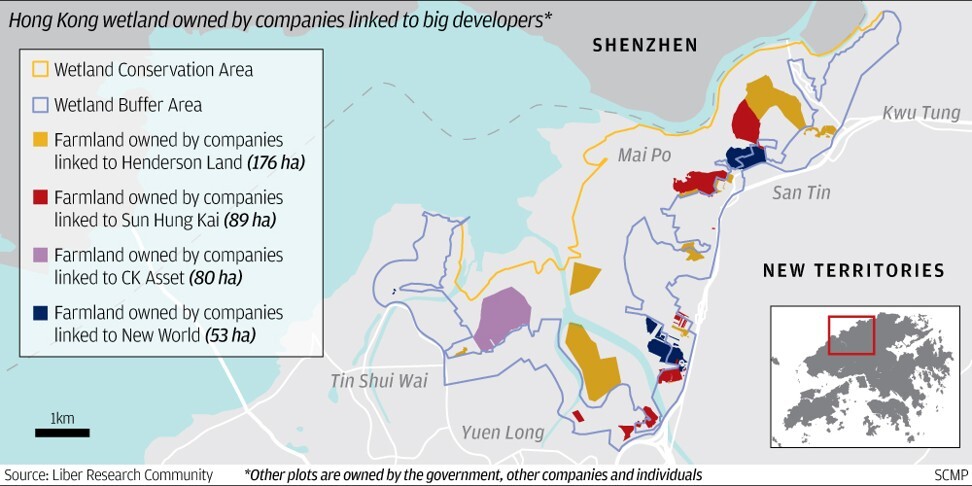

Developers also want the government to take a look again at current rules for development in the Wetland Buffer Area, a 1,200-hectare strip about 500 metres from the Deep Bay Wetland Conservation Area in the northwestern New Territories, near the border with Shenzhen.

The current plot ratio – which is the total built-up area of a development divided by the total area of the site – in the buffer zone forces developers to build multimillion-dollar villas such as SHKP’s Palm Springs, if they hope to remain profitable.

Secretary of Development Michael Wong Wai-lun on August 2 said the government was moving towards reviewing projects in the zone.

SHKP’s Kwok said: “We need a baseline on what can be developed, what needs to be conserved, the appropriate building height and the plot ratio for the parts that can be developed.”

He added that parts of the wetland buffer area were ideal for development, as they were close to Shenzhen and the Hong Kong-Shenzhen Innovation and Technology Park in the Lok Ma Chau Loop.

Why not tap green belt, clan land too?

If the developers had their way, the government could also tap part of the city’s 16,000-hectare green belt for housing.

“With each hectare yielding some 750 homes, the 1,600 hectares could produce about 1.2 million additional housing units, doubling Hong Kong’s existing public housing stock,” he said.

It is not an idea Hong Kong’s green groups take to. Peter Li Siu-man, senior campaign manager for the Conservancy Association, said it would be hard to assess the long-term impact of development on the buffer zone.

“The habitat of birds and other wildlife will be threatened after more people and vehicles enter the area,” he said.

But SHKP said its recently completed Wetland Seasons Park – located in the buffer zone next to the Hong Kong Wetland Park – had shown how homes could be built close to a protected area while also caring for conservation.

“The project was designed, built and managed with great care and consideration to protect the nearby ecologically sensitive wetland, especially the migratory birds, having fulfilled very stringent environmental requirements set by different government departments and the Wetland Park management,” a spokesman for the developer said.

The company said its Park YOHO project, though outside the buffer area, was designed to recreate a five-hectare private wetland – YOHO Fairyland – where the number of species had increased from 180 when the project was completed in 2017 to more than 300 now.

“This is another prime example showing how active management can raise the ecological value of otherwise abandoned land,” the spokesman said.

The New Territories are potentially a source of even more sites for housing, developers said, pointing to large tracts of idle, mostly unutilised ancestral “tso/tong” land, held in the name of a clan, family or tong.

About 2,400 hectares of such land has been handed down through generations and reserved only for male descendants since even before the British colonial era.

Archaic rules that apply to the ancestral land, dispersed among clansmen – many of whom are dead or have emigrated – stand in the way of combining usable plots into commercially viable housing land, Chinachem’s Choi said.

The government should review the rules and provide more flexibility to allow the sale of this land, he said.

Prudential Brokerage’s Cheung said Hong Kong’s housing crisis was multifaceted and complex, requiring a concerted effort by all concerned – private sector developers and the government alike.

“The developers are not entirely to blame, but they should obviously do more, like speeding up sales of flats,” he said.

Hongkonger Kevin Tsui ka-kin, an associate professor at Clemson University’s College of Business in South Carolina in the United States and a keen observer of Hong Kong’s housing scene, said he believed the government and developers might be under pressure from Beijing to solve the city’s housing crisis and stabilise home prices.

“Developers have become more active in providing solutions to increase land supply. To a certain extent, they want to show that they are not the ones who bear full responsibility for the crisis,” he said.

The government has also acknowledged the need to improve coordination of different departments in approving land use conversion and speeding up infrastructure in the New Territories.

“Now, it is time for the government to act fast in land creation and approving applications for property development,” he said.

The first instalment of this three-part series examines why housing demand outstrips supply in Hong Kong. The second instalment looks at the part the MTR Corporation and Urban Renewal Authority play in providing homes for Hongkongers.