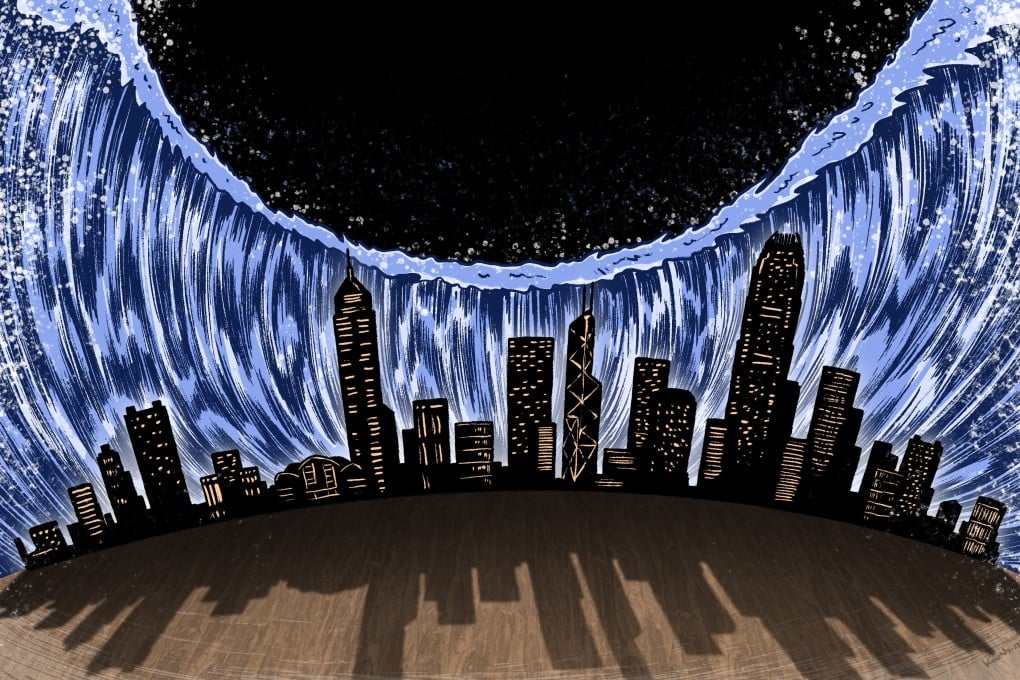

Extreme weather scorecard: Hong Kong, Macau vulnerable in Greater Bay Area as Guangzhou, Shenzhen gird for once-in-200 year storms

- The coasts of Shenzhen and Guangzhou are protected by sea walls against storm surges with the force seen once in every 100 to 200 years

- Hong Kong and Macau are less resilient against storm-surge threats from typhoons, coastal subsidence and government adaptation policies, climate advocates say

One afternoon last July, storm water crashed an underground retaining wall at Guangzhou Metro’s Shenzhou Road station, forcing the subway operator to shut Line 21 for seven hours, as a torrential downpour lashed southern China’s largest metropolis.

Guangzhou received 74.4 millimetres (3 inches) of rain within an hour that day, an unseasonably violent storm in a city that typically gets three times that precipitation over an entire month.

But what happened in Guangzhou paled in comparison with the devastation that was dumped on Zhengzhou in central China’s Henan province 10 days earlier. As much as 201.9mm of rain fell within an hour on the city on the loess plateau, setting a national high water mark since record-keeping began in 1951.

“We have no choice but to put in place no-regret adaptation against coastal threats,” said Debra Tan, founder of China Water Risk (CWR), pointing out that the latest report by a United Nations panel on climate change showed “a greater than 50 per cent chance” that the Earth’s temperature will be 1.5 degrees warmer before 2040. “It is clear that many climate impacts are irreversible, including rising seas.”