China’s ban on overseas coal power plants is good for the climate … but where’s the support for renewable energy? experts ask

- Beijing’s pledge a year ago has put a ‘significant dent’ in planned coal-fired projects overseas, says a climate report

- Greater support is needed to get low-emission projects up and running to replace the cancelled coal projects, analysts say

But greater support is needed to get low-emission projects up and running to replace the cancelled coal projects and meet fast-growing energy demand in developing nations, analysts said.

Some 24GW of the coal-fired capacity involving China is in the advanced stages of construction, mainly in Indonesia, India, Pakistan and Vietnam, while 7.6GW have been completed and commissioned.

Another 17GW has been given the green light or been financed but construction has yet to start, meaning contracts could be renegotiated for conversion to renewable projects.

A sizeable 35GW of capacity – mainly in Vietnam, Mongolia and Laos – remains in the pipeline but has yet to secure financing or approval. These plants are the prime candidates for cancellation.

Another 341 million tonnes of carbon dioxide gas could be prevented from being released each year by converting or cancelling projects that are in the pipeline, said Isabella Suarez and Tom Wang Xiaojun, the authors of the CREA and PACS joint report, though a lot more work needs to be done to achieve this.

“This would also mean over 70 per cent of the carbon dioxide at risk of being pumped into the atmosphere at the time of China’s announcement last year [could] be avoided,” they wrote.

A new coal plant has an average lifespan of four decades, which means new projects risk turning into “stranded assets” as tougher decarbonisation regulations render them economically unviable.

His announcement came a few months after the leaders of Japan and South Korea committed to end state support for overseas coal-powered plants, effectively choking off the bulk of the external financing available to such projects in developing Asia.

It said China’s support for new coal projects abroad must be stopped, while those under construction should “proceed cautiously”. Low-emission coal and carbon capture facilities were to be encouraged at overseas projects that had already been built, it added, while financial institutions were urged to provide green finance for low-emission projects on foreign soil.

The crisis has rendered gas-fired power projects unviable and resulted in widespread construction and commissioning delays in Southeast Asia.

China can play a key role, said Renato Constantino, executive director of the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities, a non-government group based in the Philippines.

“China must do more, and China can do more if only it decides to boldly take an active role in enabling an accelerating energy transition [globally],” he told a webinar last month. “Vulnerable countries want to do more than survive, they want to thrive despite a climate-constrained future.”

Indonesia is the world’s largest coal exporter and the biggest recipient of Chinese funding to construct coal power projects.

To achieve its climate goal, it must phase out coal plants that do not have the capacity to capture and store away carbon dioxide emissions by the 2050s, the International Energy Agency said in a report last month.

This will require adjusting contractual terms so that the use of the coal plants is gradually cut while investor confidence is maintained. International support should be provided to help cover any unrecovered capital, said the report.

It would cost US$27.5 billion to execute the phase-out by 2050, according to a report by researchers from the University of Maryland and Indonesia’s Institute for Essential Services Reform.

Inspired by the government’s pledge, Chinese companies and banks have been adopting their own anti-coal policies abroad as well, said Cecilia Han Springer, assistant director of the Global China Initiative at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center.

But the various promises from government and the private sector are not necessarily translating into action.

Greater efforts by policy banks and state-owned firms are needed, Springer added.

She cited the success of Chinese policy banks in helping developing countries build low-cost infrastructure, and China’s leading position in the manufacturing and deployment of renewable power equipment.

China has been the world’s largest wind power market by installed capacity since 2010, according to the Global Wind Energy Council. It has also led the pack when it comes to solar farms installation since 2013.

Global renewable energy installation volume in 2021

| Giga-watt | |

| Asia | 154.7 |

| Europe | 39.1 |

| North America | 37.9 |

| South America | 13.5 |

| Central Asia | 5.6 |

| Oceania | 2.2 |

| Africa | 2.1 |

| Middle East | 1 |

| Central America | 0.6 |

Source: People of Asia for Climate Solutions, International Renewable Energy Agency, IEA

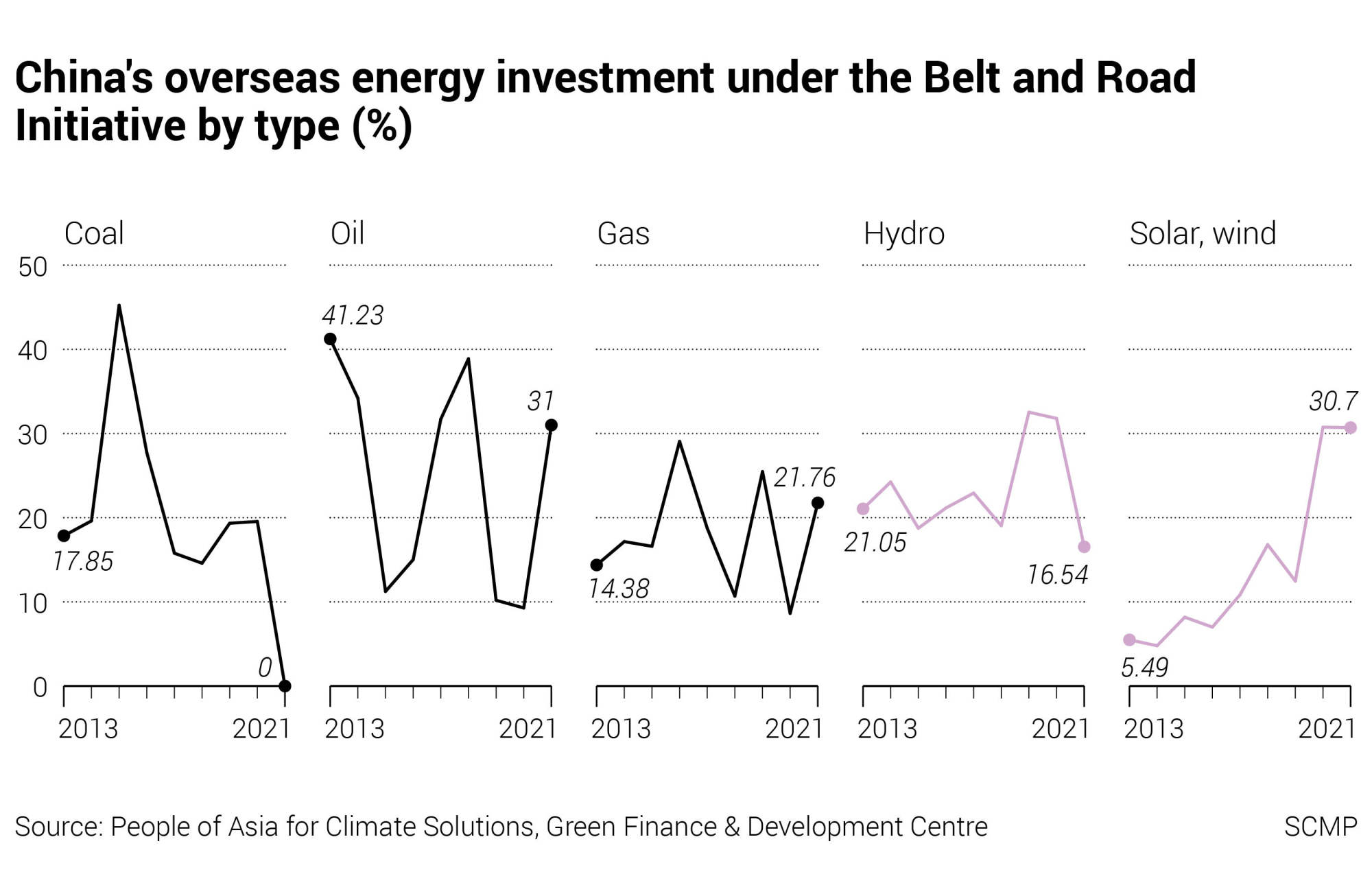

Between 2013 and 2020, of the 307 overseas power plants to which China has provided financing, some 73 per cent – by installed capacity – burned fossil fuel, according to Wang Jianye, the dean of Guangzhou University’s Institute of Finance.

That is expected to change rapidly as Asia’s energy transition gathers momentum. In the wind sector, some 729 Chinese turbines capable of generating 2.56GW were exported to the rest of Asia-Pacific last year.

That is a massive increase from 13 turbines in 2009 when China delivered a batch to India, its first export to the regional market, according to the Global Wind Energy Council.

While China’s traditional role has been focused on engineering, equipment procurement and construction for coal power projects, it has been increasingly leaning in to renewables such as solar, said Chris Starling, a partner who focuses on Southeast Asian markets at energy consultancy The Lantau Group.

“Increasingly, it has been morphing into the investor and developer space, consistent with the message the Chinese government has conveyed on its support for overseas green energy projects,” he said.

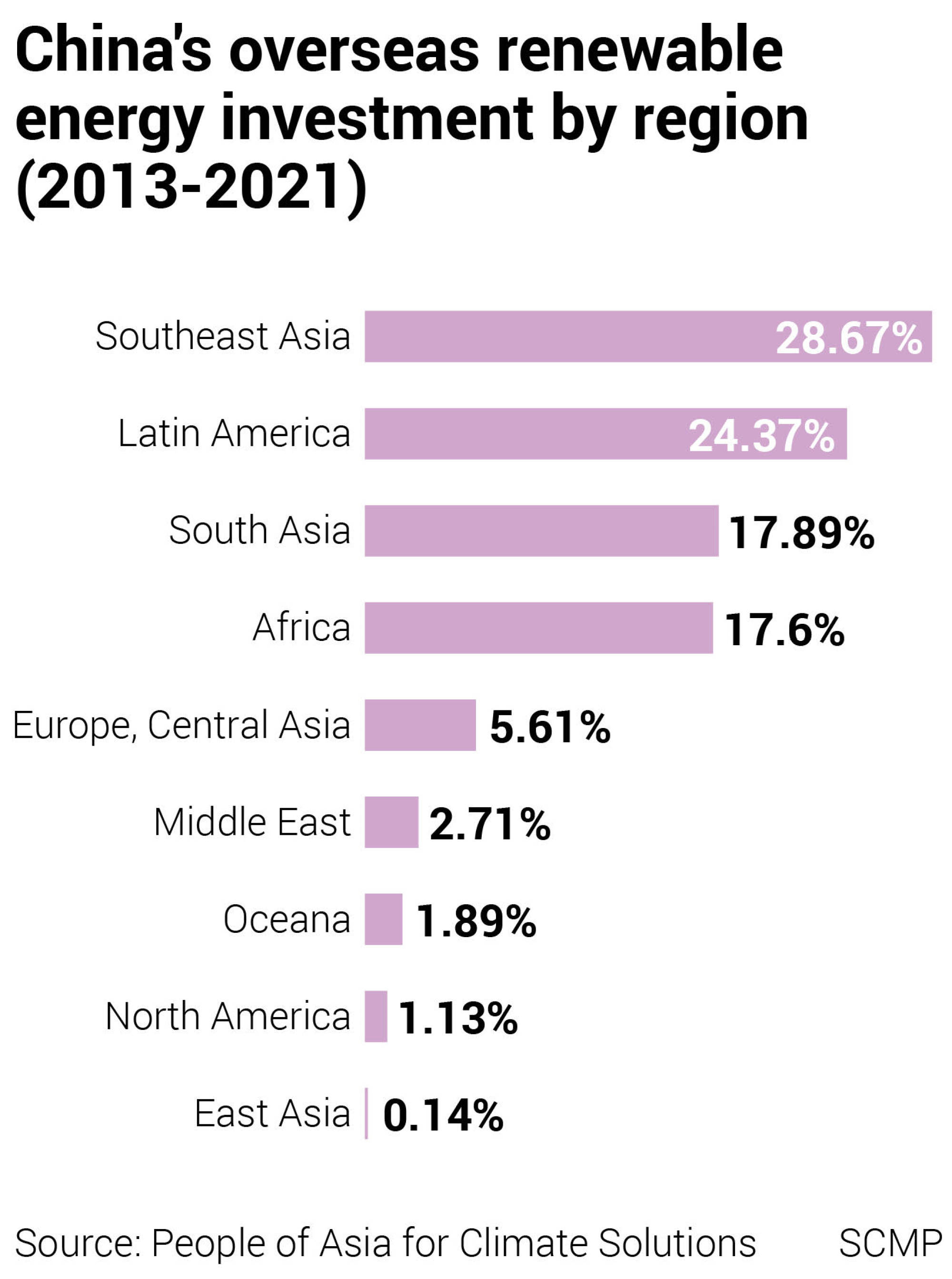

About three quarters of 52 state-backed and privately-owned renewable energy enterprises surveyed by PACS and overseas investment consultancy Odyssey Group indicated they have increased their overseas investment in the wake of Xi’s commitment to green energy investment abroad.

Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and the Export-Import Bank of China are adjusting their loans and insurance products to cater to wind and solar energy projects, they noted.

Chinese companies have shown a growing appetite for acquiring operational renewable power plants in countries with relatively stable political, legal and regulatory environments, said Ji Xiaohui, a Beijing-based partner at global law firm Linklaters.

But a significant rise in lending by Chinese banks to overseas greenfield renewable projects sponsored by Chinese firms is yet to be seen, possibly because of the long development lead time of hydro projects, the rapidly developing solar and wind energy regulatory regimes in popular destinations, and recent geopolitical instability, she noted.

Also, compared to coal projects, green projects are smaller in scale and geographically dispersed, making it more difficult to obtain financing, said Ren Peng, manager of the overseas investment, trade and environment programme at the Beijing-based Global Environmental Institute.

Moreover, even as some coal projects are likely to be swapped for renewable plants, it is important for investors to create accountability channels for communities living near the project sites, since certain green projects have been known to have a negative environmental and social impact, said Margaux Day, policy director of the US-based Accountability Counsel. It advises communities affected by internationally financed development projects seeking redress.

They should also make “proactive, timely, accurate and complete” disclosures, and be open to scrutiny by interested parties, it added.

“This is the first time there has been a public directive [stipulating] that should be the case [in China],” Day said. “The question is, will it be implemented and who is going to enforce it?”

Meanwhile, although China’s ban on new overseas coal plants has been commended, its expansion of domestic coal power capacity this year has drawn criticism.

“Although the ramp-up of coal might be a short-term policy adjustment, it poses a risk to China’s long-term climate commitments,” said CREA researcher Shen Xinyi.