Japan’s shrinking shinkin Small banks left behind by Abenomics

First the commercial fisheries began shutting down in this hardscrabble corner of Japan’s northern coast. Then tourism fizzled.

Now, the small-town bank that serves Wakkanai, at the tip of Hokkaido, is grappling with a problem common throughout Japan’s financial system: to survive years of deflation it has had to stray far from its core mission of making loans, and the easy investment income it has come to rely on is looking shaky.

“There’s no demand for productive loans,” says Masatoshi Masuda, president of the town’s Wakkanai Shinkin bank.

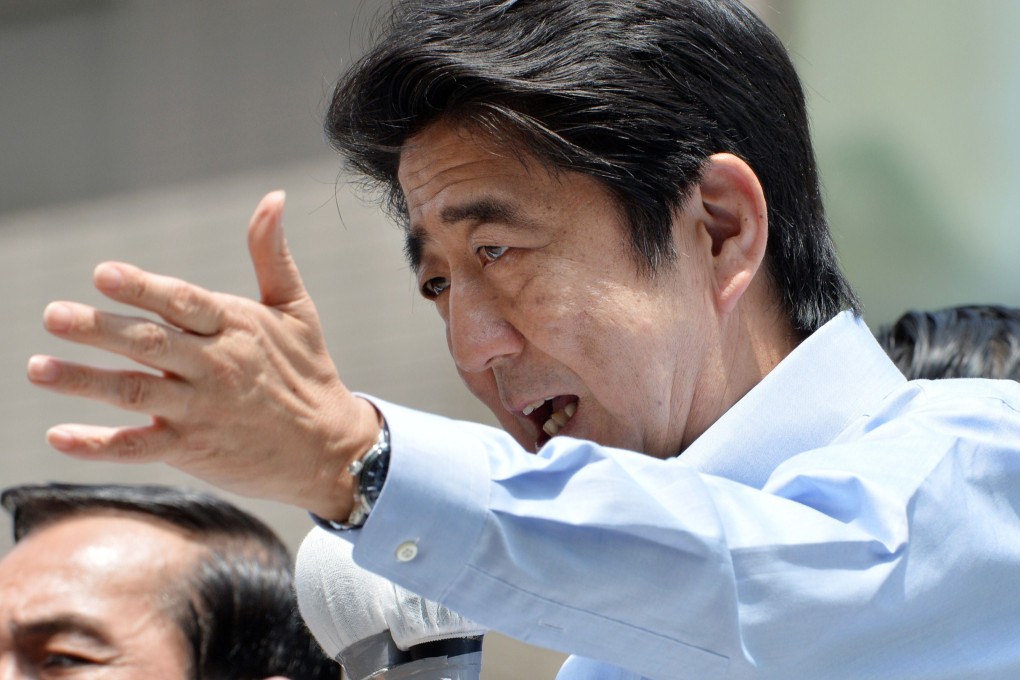

Japan’s big banks are starting to feel some benefit from “Abenomics” - the radical policy mix of massive monetary easing, fiscal stimulus and growth-orientated reforms pursued by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe since his return to power last year.

But economic revival feels a long way off in places like Wakkanai, and the country’s smaller lenders, unable to make loans to multinational companies or overseas, risk being left behind to face either consolidation or closure.

“We don’t feel any impact of Abenomics here,” said Katsumi Ogawa, an official at the Wakkanai Chamber of Commerce.

Just like Tokyo’s megabanks, Wakkanai Shinkin has plenty of cash. But very few in this port city of 38,000 want to borrow. Wakkanai Shinkin loans out only one-fifth of the US$3.86 billion it holds in deposits.