China’s industrial capacity policy is a one-way street

As Chinese President Xi Jinping visits Kazakhstan this week for Expo 2017 and deepening Shanghai Cooperation Organisation talks in Astana, it is important to understand the underlying state-to-state industrial policies at work beneath the surface.

China’s geo-industrial capacity cooperation policy is reshaping its domestic economic architecture. But for Kazakhstan, and other central Asian economies, Chinese capital in the belt and road strategy is a one-way street, exporting China’s policy as well as its banking and project models, without a reciprocal opening of its consumer or capital markets.

Capacity cooperation is an attempt to bring whole industrial clusters to China’s external markets to develop the industrial bases of its trading partners, while offshoring its cyclical overcapacity problem. The policy was launched in 2015 through the Ministry of Commerce and now pervades every aspect of China’s external industrial policy.

This combination of policy bank loans and industrial overcapacity export is effectively China offshoring its local debt problem to unwitting trading partners

A forthcoming 13th five-year plan for international capacity cooperation will list Kazakhstan as China’s ‘main axis’ to Africa, the Middle East and central Europe. The nature of the industrial cooperation policy is to offshore production clusters. Industries China is offshoring include steel, non-ferrous metals, building materials, chemicals, automotive, agriculture, construction machinery and aerospace technologies. And the intent is to bring in manufactured goods to China from Europe, Africa, the Middle East and central Asian production bases as inputs to a Chinese consumption-driven economy. It is China’s answer to Japan’s APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation).

Central funds are distributed to provincial governments, which have their own capacity cooperation policies playing to geographic, industrial infrastructure and competitive advantages. For example Gansu province is paired for investment with Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan, in the fields of mineral resources, non-ferrous metals, and energy. While Qinghai province is paired with Turkmenistan for capacity cooperation in water resources, electricity and textiles.

It has been billed by Beijing not as an outpouring of China’s excess industrial capacity but rather an alternative form of technology transfer and foreign direct investment. As China engineers a state-driven innovation strategy to lift its manufacturing quality up the global value chain, capacity cooperation partners can benefit from taking up the slack in old industries, bringing steel, cement and glass industrial clusters to central Asia.

China’s trade and investment strategies for Kazakhsan treat the country as a node within its larger belt and road geo-industrial policy

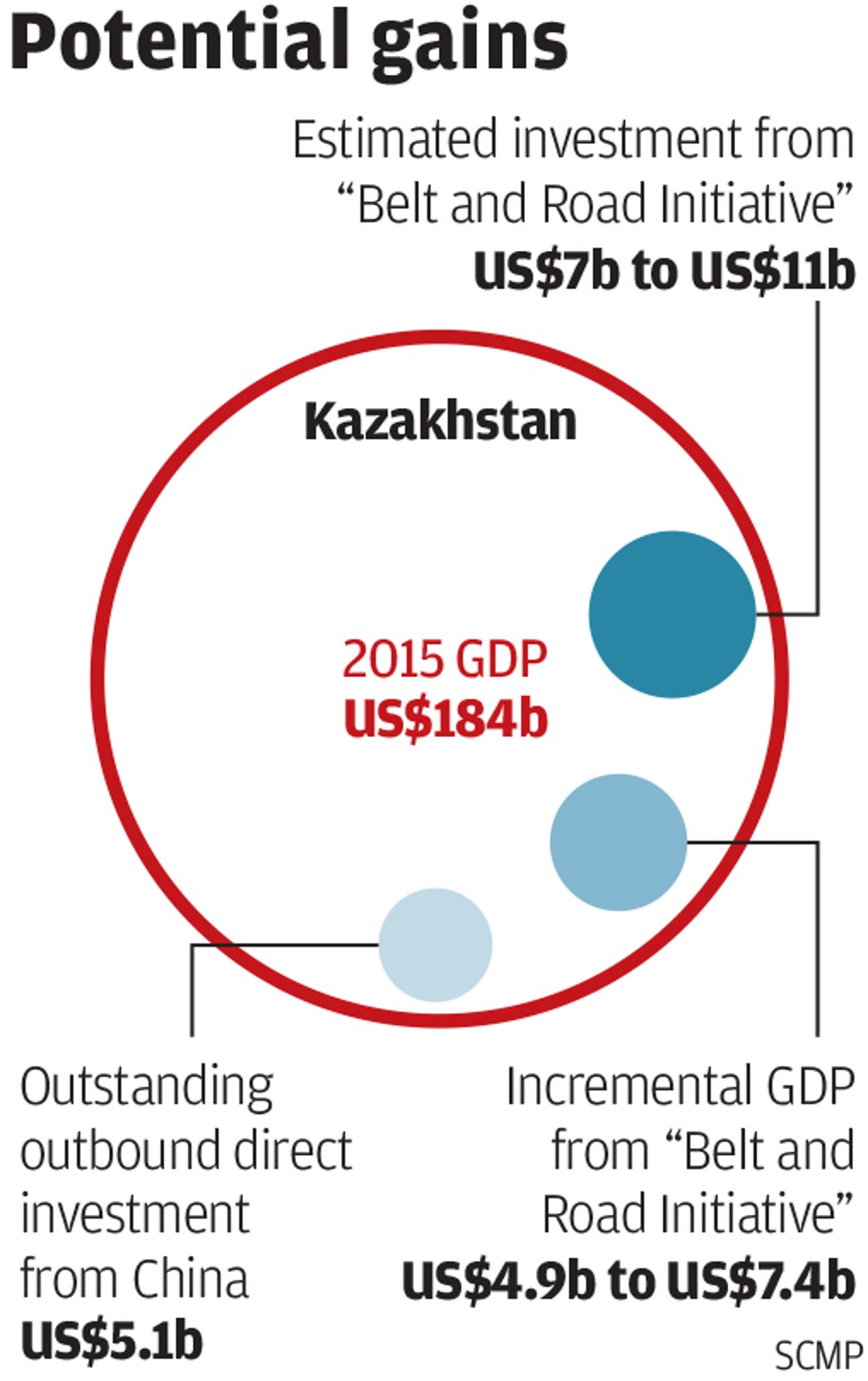

Kazakhstan’s ‘bright path’, ‘100 concrete steps’ and ‘strategy 2050’ industrial policies have been planned to intersect with China’s belt and road initiative since 2013. Fifty joint Kazakh-China industrial capacity cooperation projects were agreed to in 2015, worth US$25-30 billion over five years to create industrial cluster cooperation zones in transport infrastructure, manufacturing, construction, and agriculture. But China’s trade and investment strategies for Kazakhsan treat the country as a node within its larger belt and road geo-industrial policy.

Existing China-invested industrial projects in Kazakhstan include Kazakhstan Aluminium, Kaz Minerals copper mine in Aktogay, and Petrochina’s petcoke project in Pavlodar, all of which are at least partly funded by Beijing policy banks: the Export-Import Bank of China, and China Development Bank.

In February, Kazakhstan’s ambassador to China, Shahrat Nuryshev, met with Xu Weihong, chief economist at China’s Aviation Industry Corporation Securities, to discuss construction of a mining and chemical-metallurgical complex in Zhambyl and the development of a special economic zone in the industrial city of Pavlodar. The investment in the Kazakh industrial cluster would output metal alloys for use in China’s production of aircraft. And in March, representatives of China’s aluminium industry met in Beijing with central government officials to form the China Non-ferrous Metals International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance.

Kazakhstan’s minister for investment and development, Zhenis Kasymbek, was also recently on a working visit to China, where he met with the Ministry of Transport and representatives of state-owned enterprises in agro-industry, food, biotechnology, heavy industry, transport infrastructure, construction, insurance and finance.

Chinese fixed-capital investment in the central Asian republics’ traditional industrial bases is a geoeconomic gift they cannot afford to spurn

Chinese fixed-capital investment in the central Asian republics’ traditional industrial bases is a geoeconomic gift they cannot afford to spurn. Central Asian states have been left for decades with partially functioning or unclosed industrial complementarity loops due to being peripheral nodes in Russia’s Soviet Union continent-wide state industrial planning. Present-day water resources, transport networks, energy networks, and a variety of traditional industrial bases remain dysfunctional or isolated due to the economic destructure from Moscow.

China’s capacity cooperation policy will bring investment to Kazakhstan’s aluminium and non-ferrous metals industries, agroindustry, and transport, machinery and equipment industries. But while China’s trade with Europe will be a two-way channel, investment in central Asia will be strictly on China’s terms, effectively extending its industrial matrix into Kazakhstan for re-export to China, without opening the mainland’s deeper markets.

This is the Chinese domestic development model applied to external markets. And it effectively establishes a parallel trade and investment system, one that is tied to Chinese state-driven projects and the financial risk associated with unaudited Chinese state capital and dysfunctional local government bond markets. And it carries the seeds of a future central Asian financial crisis as unaudited Chinese debt could just as easily disappear back over the Trans Ili-Alatau mountains in the case of declining asset prices in a Chinese debt-deflated economy.

Tristan Kenderdine is a lecturer in public administration at Dalian Maritime University and research director at advisory Future Risk.