Mind the Gap | Financial corruption in China, US are two sides of the same coin

A leader fights corruption with the legal system he has, not the one he wishes he has. The ongoing fight against the extent of financial corruption in both China and the US poses particular challenges that are unique to both systems.

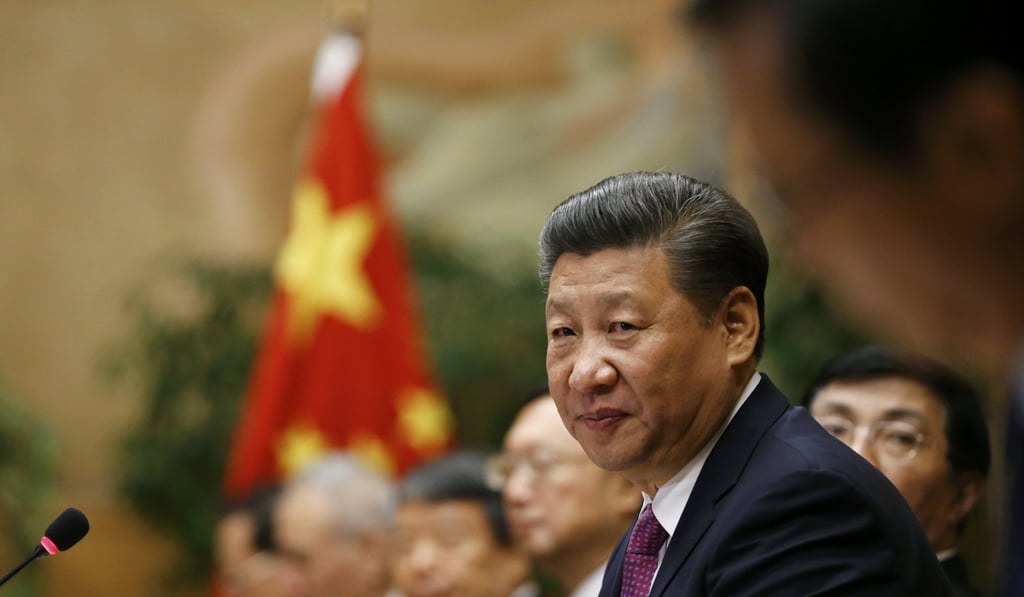

In late 2012, China’s President Xi Jinping launched a “war on corruption.” The campaign promised to purge the country and the Communist Party of chronic corruption problems by targeting both “tigers and flies”. The campaign reportedly has punished at least 140 “tigers” – senior government and Party leaders – and many thousands of lower-level “flies”.

China’s version of “capitalism with Chinese characteristics” is actually capitalism in its purest form – every person out for themselves. It requires Godfather-style authoritarianism, judgment and policies that override laws to reduce the excesses and corruption.

The challenge with “regulation with Chinese characteristics” is that the crackdown on corruption has delivered extensive powers to the Party’s secretive and much feared Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, (CCDI) which largely operates without transparency.

Purges of high profile businessmen and bankers based on social networks may work when China’s relatively closed and controlled capital accounts make it easy to trace who are the country’s big offshore investors. However, as China must move to a more open economy and global capital flows, it must evolve institutionalised banking and investment regulation and enforcement.

Russia’s Stalin learned the hard way that purges without an end only breed personal vendettas, distrust and desperate behaviour. Guo Wengui, one of China’s most wanted exiles, has copied Julian Assange’s “tell all” tactics to escape China’s authorities and embarrass officials before the October party congress. Guo has uploaded enough videos on YouTube from his US$67 million Manhattan flat that he should be given his own channel or show like House of Cards.