Chinese developers under pressure as key funding source dries up

Banks, by far the largest funding source in China’s US$11 trillion bond market, are now shying away from higher-risk, higher-yielding notes

Chinese property developers are facing a potential cash crisis as they find themselves unable to access a key source of financing amid Beijing’s crackdown on debt, according to analysts.

The country’s builders have long relied on the bond market to fund their operations and refinance existing loans, tapping a seeming bottomless pit of funds that predominantly came from banks more than willing to soak up the debt.

But that river of easy credit is quickly drying up, according to investors, securities firms and credit rating officers.

Banks, by far the largest funding source in China’s US$11 trillion bond market, are now shying away from higher-risk, higher-yielding notes, under pressure from Beijing as it tries to ward off financial risks by reducing the nation’s worryingly high debt levels.

Two sources from different institutions said commercial banks’ proprietary trading departments have been staying away from bonds rated below AA+, and have become very wary of investing in property firms and local government financing vehicles.

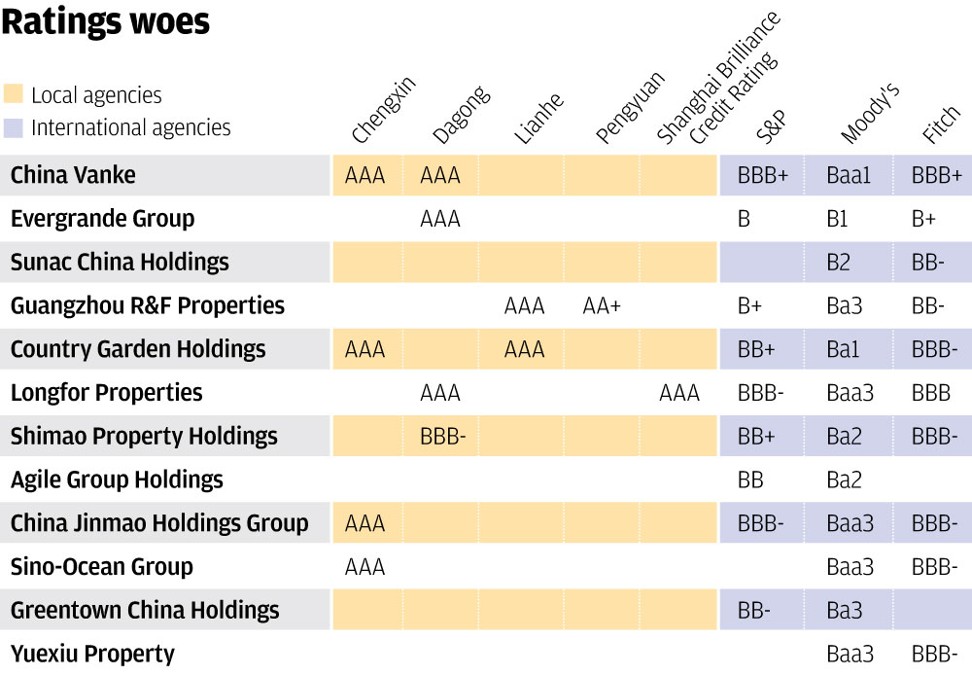

Most large Chinese builders are rated AAA by domestic ratings agencies, according to Bloomberg, but none are rated A or above by the international agencies Fitch, S&P and Moody’s.

Four mainland builders including Country Garden and Hopson Development dropped plans to sell bonds worth a combined 34.1 billion yuan (US$5.3 billion) in late May because of a lack of interest from investors.

Adding to their problems is the large amount of debt coming due. Chinese developers have to repay at least US$26.8 billion of debt before the end of 2018, and about US$200 billion over the next three years, according to Bloomberg data.

Across all sectors, 13 issuers, mostly privately held firms, have missed payments on 20 onshore bonds worth 14.8 billion yuan in the first five months of this year, according to China Chengxin International Credit Rating. In late May, China Energy Reserve & Chemicals Group and CEFC Shanghai International Group defaulted on US$600 million dollar notes, spurring a price tumble among Chinese high-yield US dollar bonds.

“A typical defaulter is one who took on excess debt during the credit splurge, and invested in lots of non-core businesses that take a long time to recover the funds,” said Mao Qijing, an analyst with China Chengxin.

The sudden and profound shift away from risk in the bond market is something they did not foresee, said analysts.

What is rattling the market’s nerves is the fact financial buffers are deteriorating. The average cash-to-short-term debt ratio of China’s listed developers, a key measure of companies’ liquidity risk, dropped to 95 per cent at the end of March from 139 per cent a year ago, according to Bloomberg. Beyond the headline number, different developers’ situations vary.

A Morgan Stanley report pointed to Sunac, Evergrande, R&F Properties and Agile as having the highest short-term debt to cash ratios. Evergrande leads the metric, with 2.34 times, followed by Guangzhou-based R&F.

Evergrande recently raised the coupon on one of its bonds by 142 basis points to 6.8 per cent to discourage investors from exercising put options.

Yuzhou Properties, a mid-scale developer, issued a three-year bond with a 6.3 per cent coupon two years ago, with the opportunity for holders to negotiate the rate in the third year. Now they are demanded 6.99 per cent.

“Otherwise they would sell the bond back to us,” said Jacky Wong Chin-hung, chief financial officer of Yuzhou. Borrowing costs have increased by 40 percentage points this year, from 10 to 30 percentage points in 2017.

Chairman Lam Lungon said the firm would strengthen its cash flow by speeding up property sales.

Higher funding costs are a problem developers have been coping with since the beginning of this year.

Franco Leung, senior vice-president of the corporate finance group at Moody’s, said mainland developers have to seek different financial channels to raise funds in the face of restricted onshore liquidity.

“The quota for onshore bond issuance, in general, has scaled back in 2018. It is no longer easy to get the green light to sell corporate bonds, particularly for property developers,” he said.

Bank borrowing costs have increased to 30 to 40 percentage points above the benchmark rate this year from a premium of 5 to 10 percentage points in the previous two years, he said. To lower financing costs, he said property firms are tapping asset-backed securities by repacking rental income or property management fees.

The decline of shadow banking, once a critical source of loans for developers shunned by banks, is a double whammy. Entrusted loans, the poster children of shadow banking that along with trust loans represented 15 per cent of developers’ funding, saw a net monthly decline in 2018 after years of rapid growth.

“The problem for many developers is not how much the funding costs, but whether they can secure funds or not,” said Xie Haoyu, a property analyst with Guotai Junan. “The pricing power is tipping towards the government, which caps selling prices, and lenders, who have raised interest rates.”

A source of relief for developers is their still strong contracted sales and solid sell-through rate. Developers with strong sales are in a much stronger position to pay short-term debt. According to TF, cash collection accounts for 43 per cent of listed developers’ funding, the largest share, while loans take up 28 per cent, and bonds only 3 per cent.

Tight credit conditions have pushed more developers to raise funds offshore, and the urgency has given offshore investors the upper hand when demanding a premium. Chung said unlike onshore investors, offshore investors now have enough positions, and are “happy” to seek opportunities in junk bonds in China.