Cathay Pacific averts financial collapse with distress call to tap the HK$4 trillion war chest of Hong Kong’s financial tsar

- The Hong Kong government wanted to dress up the bailout dubbed Project Apollo as a “short-term investment” amid political scrutiny

- Bailout size grew during negotiations to restore confidence among creditors and investors in the airline's survival

Hong Kong’s Financial Secretary Paul Chan Mo-po had little time to celebrate his 65th birthday in mid-March, as he would soon pick up a call asking for the famously laissez-faire city government to undertake its biggest corporate bailout in two decades.

The bailout, larger than the HK$3 billion rescue of the city’s third-largest commercial lender the Overseas Trust Bank in 1985, would only be surpassed by the HK$118 billion bailout when the city’s blue chip stocks and currency came under attack during the 1997/98 Asia Financial Crisis.

But the following account assembled by South China Morning Post shows why the government’s intervention was critical to keep the airline’s delicate shareholding balance, and why public sector ownership would ultimately be short term, and possibly profitable.

As executives of Cathay Pacific and Swire poured over the airline’s dwindling finances in the first quarter, the size of the rescue plan was swelling by the day.

Every day throughout February, one regulator after another would serve the airline with flight bans and quarantine notices as the coronavirus outbreak spread from central China, Cathay Pacific executives said. Flights to more than 190 global destinations were grounded, some notices received while a flight was mid-air.

By early March, the cascade of travel bans left nine out of every 10 of Cathay Pacific’s passenger planes standing on the tarmac, leaving only the cargo freighters in the air. The airline – barely out of its three-year transformation plan to improve its earnings, was bleeding HK$2.5 billion to HK$3 billion every month, fast depleting its HK$14.9 billion of liquid funds at the end of 2019.

03:42

Hong Kong flagship airline Cathay Pacific hit with financial trouble amid coronavirus outbreak

The quest for a solution fell to Cathay Pacific chairman Healy and chief executive Augustus Tang, both corporate veterans who worked their way up the ranks at the airline’s parent Swire Pacific. Healy joined in 1988, Tang in 1982, but both were less than a year into their roles at Hong Kong’s hometown carrier when the pandemic unfolded.

They dubbed their mission Project Apollo, a nod to the Olympian deity of Greek mythology who delivers people from epidemics, and an acknowledgement of the enormity of their moon shot task.

The Gordian knot in any capital injection was Cathay Pacific’s structure, maintained as a delicate balance between three shareholders – Swire Pacific, Air China and Qatar Airways – owning 85 per cent of the airline, held together by several regulatory tripwires.

Swire Pacific, the 45 per cent owner of Cathay Pacific, had just ended its least profitable year since going public in 2008. It would struggle to staunch the airline’s cash bleed, especially given that Hong Kong’s recession was eating into its revenues from commercial and retail real estate.

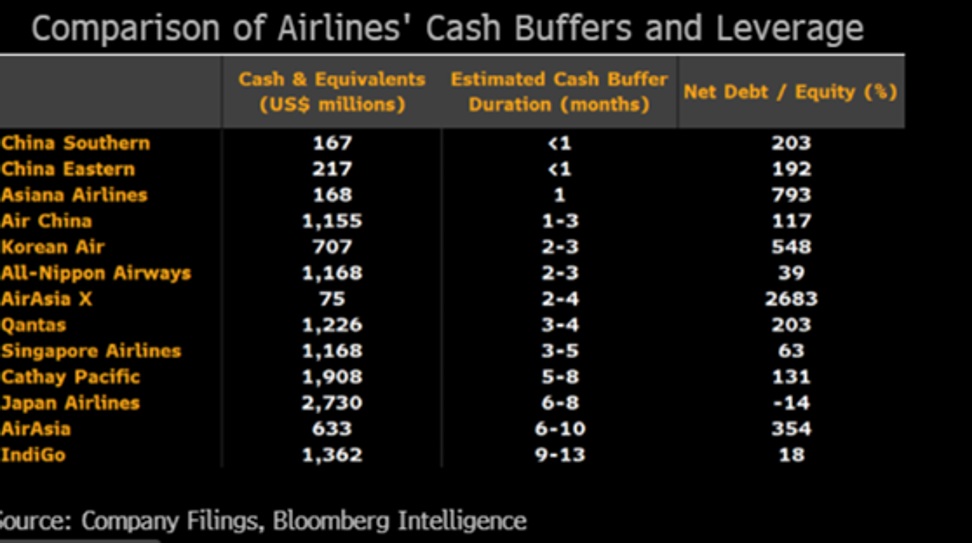

Air China, the second-largest holder with 29.99 per cent, must be kept below a 30 per cent threshold to avoid triggering the city’s takeover code. China’s flag carrier airline had its own problems, not least its grounded fleet – almost triple Cathay Pacific’s size – and 50,000 employees to care for, not to mention a much weaker cash buffer that could see it survive three months at most without revenues or a bailout, according to Bloomberg data.

Topping all the constraints, Cathay Pacific must be controlled by a Hong Kong-based entity by law, or forfeit its landing and take-off slots at the local airport, one of the biggest aviation hubs in the Asia-Pacific region.

Hong Kong’s government could not countenance the prospect of mass lay-offs of Cathay Pacific crew and workforce, not while the city was at the start of its worst recession and unemployment crisis in decades.

A day after Hong Kong’s border closure on March 26, Singapore’s government offered a financial lifeline for the city state’s flag carrier. Temasek Holdings, the Lion City’s investment vehicle and the largest shareholder of Singapore Airlines, backed a S$19 billion (US$13.6 billion) refinancing plan for the carrier. The plan comprised a S$5.3 billion sale of new stock, a S$9.7 billion issue of convertible bonds and a S$4 billion bridging loan.

The intervention by Temasek, which already owned 55.5 per cent of Singapore Airlines, made the process straightforward, but pointed the way for Cathay Pacific to get out of its quandary.

The airline hired Morgan Stanley to structure a plan at the end of March, people familiar with the matter said. A Morgan Stanley spokeswoman declined to comment.

A pitch was quickly put together and presented. The Hong Kong government auditioned banks to advise it on Cathay Pacific's predicament, choosing Goldman Sachs over JP Morgan for the mandate in early April. Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan spokespeople declined to comment.

The deal team was particularly fearful of a leak, given Hong Kong’s febrile political climate. They worried that the brewing bailout could turn into a political football in the city’s Legislative Council and delay the capital injection passed the point that Cathay Pacific could be saved.

To preserve confidentiality, they restricted electronic communication and avoided using Cafe Gray Deluxe, the upmarket restaurant on Level 49 of Pacific Place, a Swire property with sweeping views of Victoria Harbour and the favourite hobnobbing place for the company’s executives.

In the Cathay Pacific rescue, air cover came from a spree of global bailouts of airlines. Since the coronavirus pandemic broke out in January, global governments had poured US$123 billion of financial aid into airlines all over the world, IATA said in May.

Instead, Chan deployed the HK$219.7 billion Land Fund, part of the city’s fiscal reserves, and a financial war chest that was usable at his discretion. A key attraction of using the Land Fund was it would allow the government to bypass the city’s Legislative Council, where filibustering sessions had gummed up the legislature’s decision-making ability. The deal had the potential to generate a higher return than the Land Fund.

An early draft of the deal involved a convertible bond, designed to be much more favourable to investors than the mandatory and callable debt issued by Singapore Airlines and taken up by Temasek, according to people familiar with the matter.

The idea was ultimately rejected as a convertible bond would have created too large a stock overhang, one of the people familiar said. Another noted that the government did not want to become a significant equity shareholder in the airline.

The package that finally landed was a HK$11.7 billion rights issue, with the government extending a HK$7.8 billion bridging loan to Cathay Pacific and subscribing to HK$19.5 billion worth of preference shares. As a sweetener, the government would get HK$1.95 billion in warrants that are detachable and can be sold above the strike price of HK$4.68.

The deal was carefully balanced. Interest repayments – estimated by Goldman Sachs on June 9 at HK$585 million per annum in the first three years – could not drown Cathay Pacific so deep in debt that it would go belly up. At the same time, the government needed to present taxpayers with a profit and clarity on how it would exit the airline.

The deal incentivised the airline to repay the government as the preference shares’ interest rate will ratchet higher after three years and the bridging loan would mature within 18 months once claimed.

Ministers also wanted to be able to tell taxpayers that the government had protected the future of Hong Kong as a transport and business hub while making a profit to boot. The government is targeting an internal rate of return on the capital injection of 4 per cent to 7.5 per cent.

01:29

Hong Kong government to bail out Cathay Pacific with HK$30 billion in loans and direct stake

Cathay Pacific must now secure the nod of its shareholders for its right issue, due at an extraordinary meeting on Monday. That is a formality, as the carrier’s three largest shareholders have already agreed to the plan, while the remaining 15 per cent of shares in public hands are underwritten by banks.

The rights subscription price of HK$4.68 is a 35 per cent discount to the theoretical ex-rights price of HK$7.20 and a 47 per cent discount to the price on the last trading day before bailout announcement. It is likely to be hotly debated at the EGM. The stock was trading at around HK$7.24 on Thursday, down 48 per cent since hitting HK$13.90 on April 18 last year before the anti-government protests kicked off, but still higher than during SARS epidemic when the stock slumped to HK$6.50.

Since the bailout’s announcement on June 9, Cathay Pacific has been drawing down on credit lines at its relationship lender banks until the rights issue is fully paid by the middle of August. It could also tap private investors again for equity and debt, potentially reviving its shelved plan for a convertible bond.

Management are slated to recommend to the board the optimal size and shape of the group between October and December.

Cathay Pacific does not plan to merge or sell Hong Kong Dragon Airlines, as it does not want to lose the wholly owned unit's rights to fly routes across mainland China, according to people familiar with the airline. Still, some route rationalisation between Cathay Pacific, Cathay Dragon and HK Express can be expected, they said.

The bailout gave Cathay Pacific roughly 15 months' worth of cash burn, stock analysts calculated. Some of the analysts think the flag carrier could use the funds to expand as the coronavirus has passed its peak in Hong Kong and travel bubbles are gradually forming, enveloping the city and neighbouring territories.

Whatever the next couple of years hold for the airline, the feeling among the deal team is that they’ve raised more than enough capital to keep the flag carrier flying.

03:03

Airports in Asia left deserted amid coronavirus pandemic