China going after Big Tech’s monopoly in financial data to curb abuses and protect privacy, says regulator

- CBIRC flags upcoming rules to curb Big Tech’s use of data in financial services

- Some 27 million micro and small enterprises had taken out bank loans at the end of October, CBIRC says

China will look to crack Big Tech’s monopoly in financial data so that it can curb abuses of power and protect consumers’ privacy, according to the country’s banking and insurance watchdog.

The Chinese government is seeking to clarify data ownership rights as it recognises that data is a major economic production factor, together with labour, capital and technology.

“Clear ownership is fundamental” to the allocation and pricing of data, Guo Shuqing, chairman of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC), said via video during a digital financial technology conference in Singapore.

To date, few jurisdictions have specified the ownership of data properly with the European Union becoming an early leader in the protection of consumers’ privacy.

China’s move to monitor data collection is in line with international regulators’ thinking. Most recently, South Korea legislated amendments to the ‘Use and Protection of Credit Information’ in August, which were in turn in similar vein to the European Union’s ‘General Data Protection Regulation and Payment Services Directive’.

Big Tech platforms, including those owned by Tencent Holdings, Baidu and Alibaba Group Holding, fend off competition because the data sets they have amassed cannot easily be shared or accessed by potential competitors, let alone be split as a result of regulators forcing a break-up of a platform, according to a study by the University College London. Alibaba owns the South China Morning Post.

The study recommends that countries regulate data from the bottom up, restricting the capture and use of data.

“Without data, a decision-maker is just a puppet … this has been feeding a dystopian scenario built on top of an oligopoly,” said UCL associate professor JP Vergne.

Big Tech has de facto controlled all the data in China, said Guo. “It is necessary to clarify the data rights of different parties soon” to improve the flow of data, pricing and protect owners’ interests.

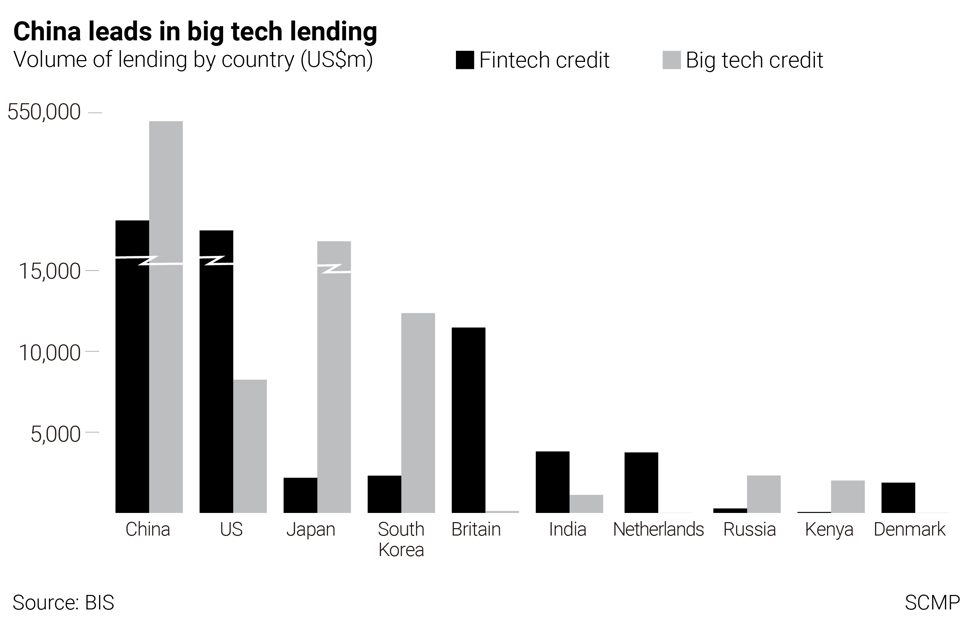

China has rapidly become the world’s largest market in Big Tech credit based on the collection of alternative data, such as shopping habits and residential addresses.

At the end of October, 27 million micro and small enterprises had taken out banking credit, while loans for these firms and the self-employed grew by over 30 per cent year on year. Loans specifically to farmers grew by 14.3 per cent year on year, said Guo.

Some tech companies use their market advantage to improperly collect, use, and even sell users’ data, said Guo.

“Without users’ authorisation, those activities seriously violate business interests and individual privacy,” he added.

Internet financial companies tend to induce overspending through overmarketing of loans and overdrafts. When default occurs, coercive loan collection causes many social problems, said Guo.

“I have more online loan application apps than any other [type of app]. Spending money by borrowing is just too easy – until they cut your credit line,” blogged a 25-year old under the pen name Silence on a creditors’ support group called “Debtors’ Union”. Silence said she had lost her job due to the pandemic earlier this year.

“They even offer loans to students without repayment abilities,” said Guo. “We insist on applying unified regulation by business activities and stand firmly against regulatory arbitrage.”

Regulators are following up on their initial broadside attack on market abuses of power. China is drafting tougher legislation to enhance the protection of individuals’ information as well as robust financial data security regulation.

“Chinese government has made [an] effort to plug the holes,” said Guo. “All these [new rules] aim to build effective protection and prevent data leak and abuse.”

A key driver in this push is fear about cyber resiliency as finance shifts online, from defence against hackers and malware to outages caused by the heavy drain on electricity.

More than 90 per cent of China’s banking transactions have moved online, said Guo adding that compared with conventional risks, cyber risks spread faster and wider and have a greater impact.

Guo said that China’s regulators will seek to understand if Big Tech has blocked the entrance of newcomers into the market; if Big Tech has collected data improperly and if platforms had misled customers and refused to disclose information that should be made public.

Mobile payments are “key financial infrastructure with public interests at stake”, said Guo.

Additional reporting by Enoch Yiu