US funds ignore China tiff, turning to world’s second-largest economy to solve a trillion dollar problem: where to find yield

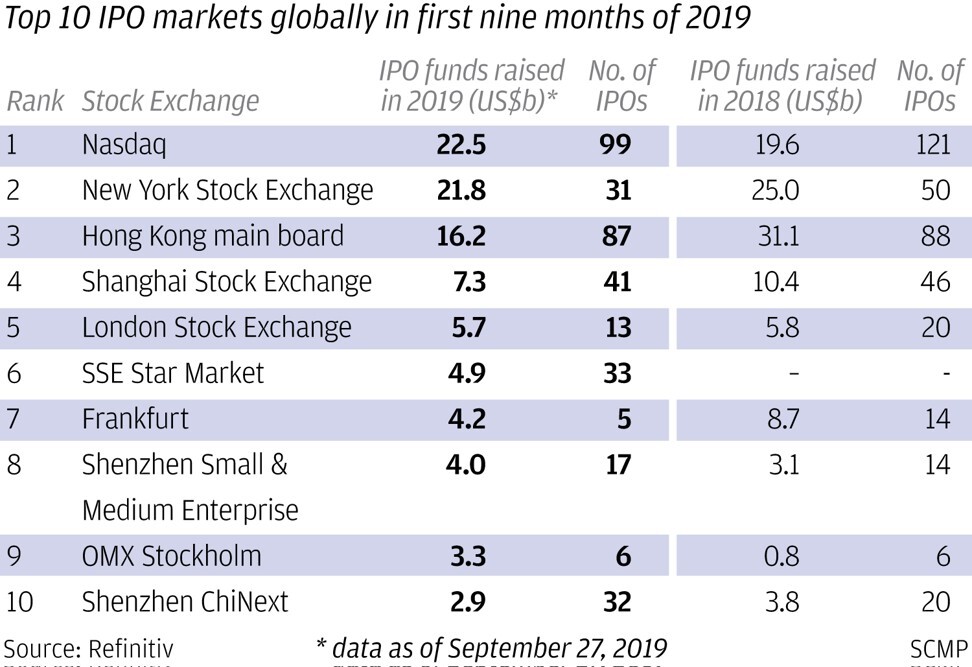

- The average value of new listings by Chinese companies rose 204 per cent last year in the United States, outpacing the 49.6 per cent gain by American IPOs or the 30.9 per cent increase among European companies, according to Bloomberg’s data

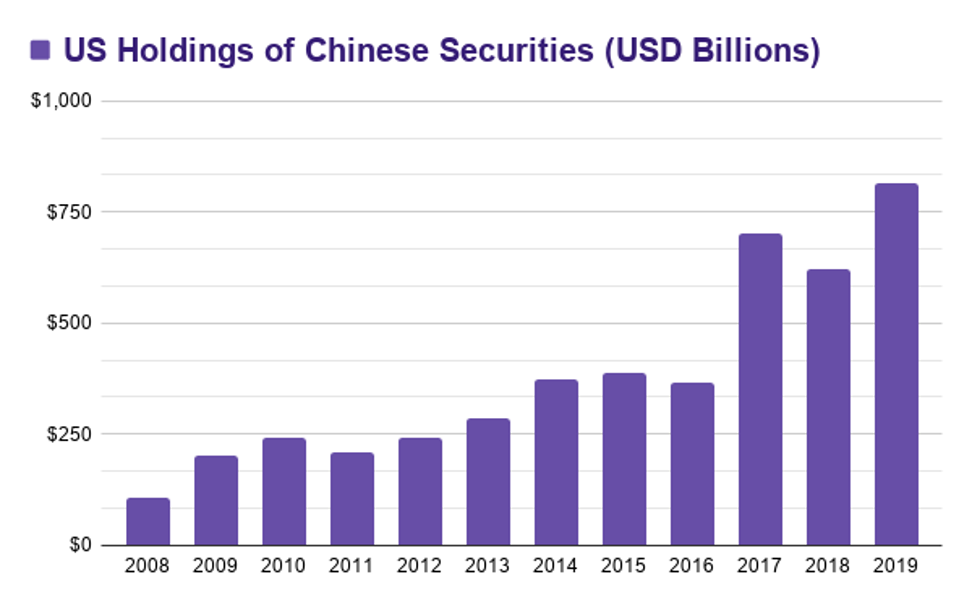

- American investors owned US$813 billion worth of stocks and bonds issued by mainland Chinese companies at the end of 2019

In the first of a two-part series on global capital flows, Jodi Xu-Klein reports on how American institutional investors and fund managers are looking beyond the lowest point of US-China relations to pour their funds into Chinese stocks, bonds, exchange-traded funds and other assets in search of higher returns in an age of zero interest rates. Click here for the second part.

“The US is just awash with liquidity, a lot of money sloshing around,” said Adam Lysenko, analyst of China’s international investment flows at Rhodium Group. “Investors are just going to keep investing in China until they can‘t any more.”

Flush with zero-interest capital unleashed by the Federal Reserve to bolster an economy wrecked by the coronavirus pandemic, US private equity funds, asset managers and pension fund investors had been making a beeline for China over the few months in search of yield.

Encouraged by signs of the world’s second-largest economy mostly back to pre-pandemic levels of production, they have snapped up Chinese stocks, bonds, exchange-traded funds and other financial assets available to them under the country’s tightly controlled capital account.

BlackRock, the world’s largest money manager, with US$8.7 trillion of assets under management, is one such investor. The New York-based investment manager said in January that it saw “a clear case” for allocating more of its portfolio to assets exposed to China.

American investors owned US$813 billion worth of stocks and bonds issued by mainland Chinese companies at the end of 2019, according to analysis of the Treasury data by Seafarer Capital Partners, an investment advisory firm focused on emerging markets. That’s more than double the US$368 billion in holdings three years earlier.

While 2020 data is not yet available, “it is reasonable to assume that the value grew even larger due to A-share inflows and market appreciation,” said Nicholas Borst, director of China research at California based Seafarer.

“I expect US investment exposure to China to continue to increase in the years ahead,” said Jay Pelosky, founder and chief investment officer at TPW Advisory, an investment adviser in New York. “China was the first into Covid-19 and the first out of [the pandemic], and the only major economy that‘s showing year over year growth.”

The gap in economic growth resulted in discrepancies in bond returns. Slower growth in the US has prompted the Federal Reserve to slash interest rates to stimulate the economy, a policy that drove inflation-adjusted Treasury yields precipitously to negative 1 per cent, according to Mitsubishi-UFJ Financial Group’s report.

“As a fixed income investor, if you can offer me a 3 per cent yield on a 10-year government paper with an appreciating currency, I will want that,” Pelosky said. “And I’m going to want a lot of it.”

That appetite propelled investors to look for direct ways to invest in China, an avenue that had been hitherto off-limits to offshore capital due to the country’s capital controls.

As part of the plan, China loosened up investment policies and overtook the US last year as the world’s top destination for new foreign direct investment, including mergers, acquisitions and investments directly into businesses.

China’s moves suggest the nation is also keen to attract foreign capital to its financial markets. That could not have come at a better time for funds that have been historically underinvested in the country because of the various barriers of entry.

US investors accounted for only 6.5 per cent of the Chinese equity market’s capitalisation, according to Seafarer, compared with 15 per cent in Japan and more than 25 per cent in the UK.

In the debt market, even including government bonds, US investors made up just over 2 per cent of the US$12 trillion of the Chinese onshore bond market in 2019, Seafarer data show. US capital held 12 per cent of debt in Japan and 39 per cent in Indonesia.

There are still plenty of challenges investing in China where foreign capital flow was strictly controlled until recently. For one, onshore bond ratings have long been criticised for not providing nuanced credit information. More than 70 per cent of the issuers are rated above “AA” investment grade near the top of the local ratings spectrum.

Some investors’ enthusiasm had also been damped by financial scandals involving US-listed Chinese companies, such as the accounting fraud by Luckin Coffee, the Xiamen-based pretender once dubbed “China’s Starbucks”.

US-China relations remain an overhang, as the 46th American president is yet to hold a phone conversation with his counterpart Xi Jinping, with whom the two have had many decades of working relationship.

“The aggressive imposition of financial sanctions against Chinese companies is going to be seen as an aberration, not as a policy that’s likely to be continued,” said Pelosky.

“There are always geopolitical risks investing in China,” he added. “But up until now, the economic relations have continued, even though there are geopolitical problems. Americans are underweight China, so it’s natural that different American interests are trying to invest in Chinese stocks and bonds as part of a diversified portfolio. That makes sense.”