Climate change: measuring transition risks from net zero global challenge, central bankers, policymakers tell Green Swan Conference

- Global framework needed to appropriately measure climate risks, policymakers, central bankers at Green Swan Conference say

- Stranded assets from transition may range from US$1 trillion to US$4 trillion, one study found

So-called physical risks from climate change – economic costs associated with more extreme weather events – are relatively measurable, but transition risks are a more complicated calculus, according to Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

“It would play over time and it would demonstrate itself as we move towards lower carbon intensity forcefully,” Georgieva said at the Green Swan 2021 conference. “We need to look into this risk already today.

“The dirty assets: how are they going to evolve. Their value will decline, would be replaced by others. How do we integrate this is a question we are wrestling with.”

03:27

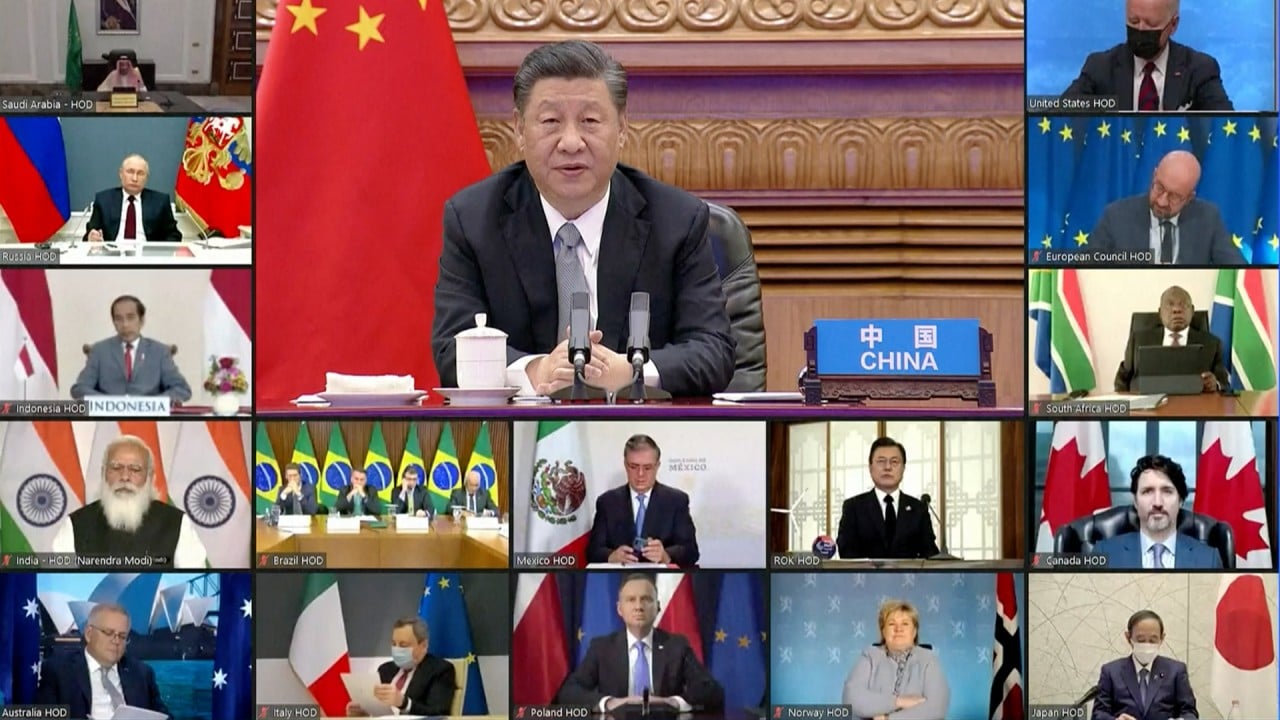

World leaders pledge to cut greenhouse emissions at virtual Earth Day summit

Policymakers, advisers and business leaders gathered virtually last week at the Green Swan conference to discuss how to address the climate crisis and incorporate climate targets into financial policy. The conference was co-sponsored by the Bank of International Settlements, the Banque de France, the IMF and the Network for Greening the Financial System.

Co-signers to the 2015 Paris Agreement have agreed to work together to cap peak emissions on greenhouse gases and to seek to limit global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius when compared with pre-industrial levels.

To better manage the economic risks from market-based carbon reduction policies such as emissions trading, China – the world’s largest greenhouse gases emitter – should speed up the establishment of road maps for each of the 24 major industries officials have identified, as soon as possible, said Zhou Xiaochuan, a former governor of the People’s Bank of China.

“We didn’t have a good enough preparation for that in terms of planning and data [collection] when the climate goals were announced,” Zhou, currently president of China Society for Finance and Banking, told the conference on Friday. “There are great risks to be expected from carbon markets, we may make some mistakes that we will later need to correct, and which may be costly.”

China is due to start spot market trading of carbon emissions in a newly set up national exchange in Shanghai to finance carbon emission projects as soon as this month. Seven operating pilot regional exchanges will eventually be integrated into the national exchange.

Zhou urged other large developing economies to also set up carbon emissions markets to show their determination to implement their climate commitments. At some point, connections among international carbon markets should be considered to provide channels to facilitate financial support and technology transfer from developed to developing nations, he said.

This could be achieved by implementing mechanisms similar to the cross-border Stock Connect schemes that allowed controlled fund flows into and out of stock markets between China and other jurisdictions, he added.

One prominent issue for global leaders is how to deal with older, heavy carbon-emitting industries that may find their assets “stranded” as a result of the shift to net-zero economy.

A disorderly transition to a low-carbon economy could lead to increased credit risk in some industries, namely by reducing the ability of some businesses to service and repay their debts, according to the Financial Stability Board.

The financial effects of the shift to a low-carbon economy remain hard to pinpoint.

One study estimated the loss in global wealth from stranded assets may range from US$1 trillion to US$4 trillion, according to the FSB. However, reductions in the value of equities and bonds held in financial sector portfolios could reach US$2 trillion alone, which would be less material for financial stability if they occur gradually, according to the FSB.

Climate activists are putting pressure on companies and their lenders to rethink their use of and support of the fossil fuel industry, with activists winning key support from shareholders at ExxonMobil and Chevron in May.

“We’re taking it as our mission to help our clients understand their sustainability and their climate position, their position on greenhouse gases to help them transition themselves,” Winters said at the company’s annual meeting on May 12. “Where we have clients who are unwilling or simply unable to make the transition, they won’t be able to bank with Standard Chartered.”

Reaching those climate goals, in part, will require mandatory disclosure by the private sector of climate risks to their businesses under standards set by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), according to Mark Carney, the former Bank of England governor and UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance.

“We know that climate risks are different from traditional financial risk. They’re economy wide. They affect every consumer, every business, every sector. They’re global,” Carney said. “They’re longer term going beyond the usual three to five-year planning horizon for most businesses.”

All major jurisdictions should adopt “pathways to comprehensive, compared climate disclosure” based on those recommendations by the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, known as COP26, in November, he said.

Gang also said China was “positive” on the TCFD, asking the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, to join as a member.

“Our goal is to make a uniform disclosure standard, and in the future, we will go in the direction of a mandatory disclosure of climate-related information.” Gang said during a panel at the conference on Friday.

“There is no template for a comprehensive framework for greening an asset portfolio held for monetary policy purposes,” Andrew Bailey, the Bank of England governor, said at the Green Swan conference. “We know that outreach and engagement is critical in getting this right, and so are currently seeking feedback on our proposed framework.”

One challenge is there is no universal framework for climate reporting, even though the TCFD standards go a long way to standardising the process, policymakers said.

“We’re not quite yet on sound footing to have uniformity of standards. [There are] 200 frameworks. It is a little too much to handle,” Georgieva, the IMF managing director, said. “We have to go towards narrowing down and accepting that mandatory can only be done when we have a commonality of standardised exposure and accepted frameworks.”

Additional reporting by Finbarr Birmingham