China’s carbon neutral goal: Shanghai emissions contracts to start trading in July, using market prices to drive towards target

- Electricity generators will pioneer the mandatory trading of carbon emission contracts, due to start at later this month

- The trial will be followed by construction materials, steel, petrochemical, chemical, non-ferrous metal, paper and aviation

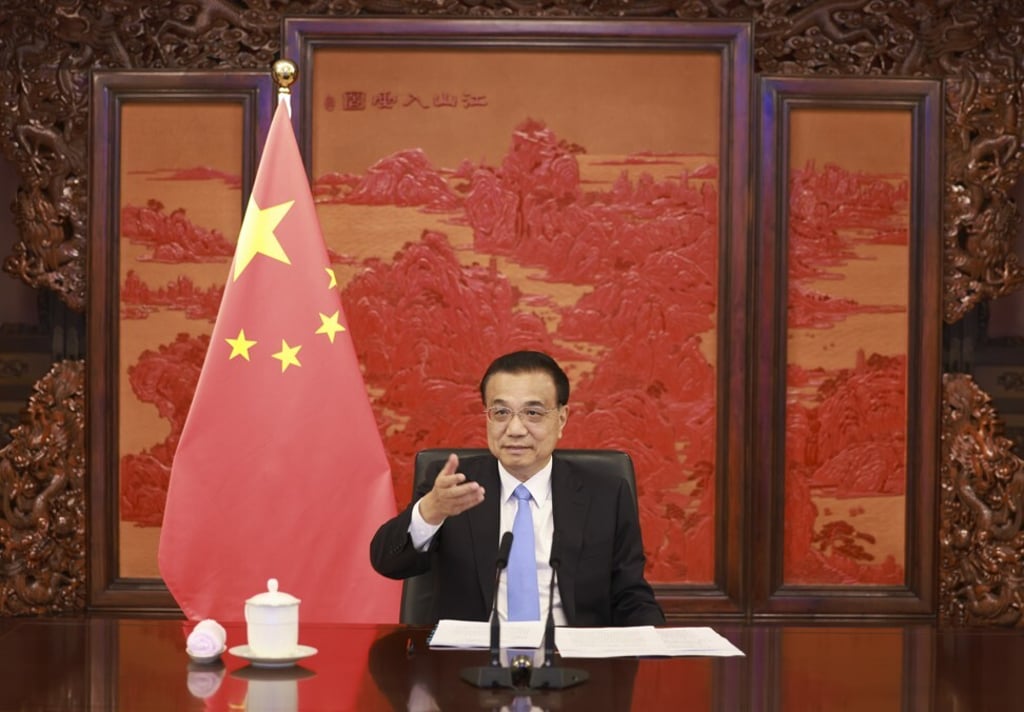

Leading the charge on the Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange will be power plants and electricity generators – estimated to be responsible for 40 per cent of China’s carbon dioxide emissions – before seven other carbon-intensive industries join in the mandatory trading, according to a statement by the State Council, citing a directive by Premier Li Keqiang.

“Trading will be expanded to cover more industries subsequently so that greenhouse gases emission can be reduced by market forces,” according to the statement, which did not provide a schedule. The remaining industries are in construction materials, steel, petrochemical, chemical, non-ferrous metal, paper and aviation.

The impending commencement is a crucial part of the plan by the nation responsible for 30 per cent of the world’s annual greenhouse gases to reverse the trend, through a mechanism that puts a price on emissions, prompting companies that exceed their caps to buy quotas from energy-efficient companies.

President Xi Jinping surprised the world last September with his unexpected pledge at the United Nations for China to reach carbon neutrality, becoming the second major economic entity after the European Union to put a date on that promise.