LME’s nickel rout: the world’s metals trading hub grapples for its mojo after unprecedented trading snafu

- Some traders are questioning whether the Shanghai Futures Exchange or the CME should play a bigger role in metals market

- Suspension of nickel trading, slow return of market following a short squeeze has raised concerns about LME’s approach to the nickel price crisis

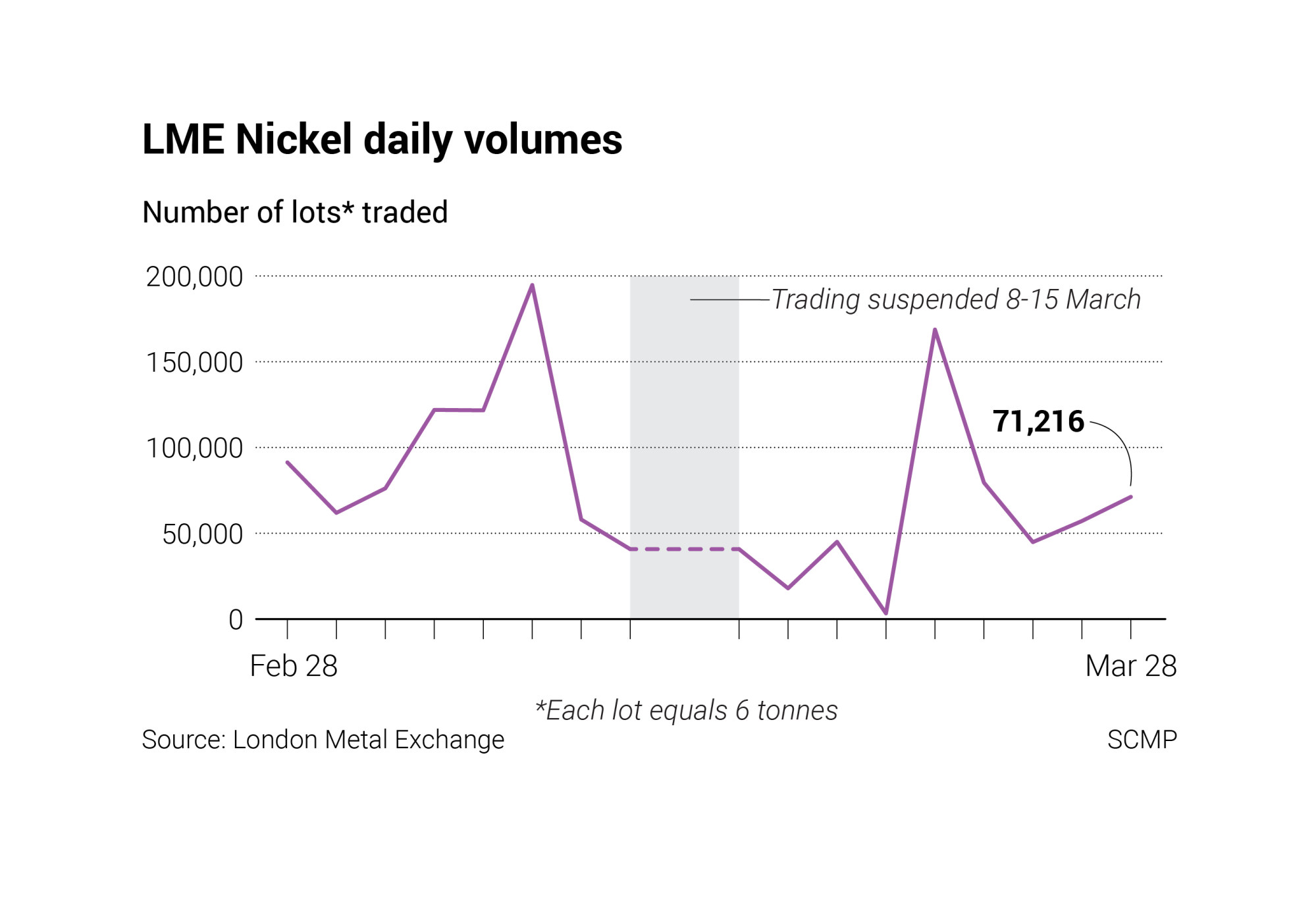

Electronic trading, which resumed a week later after Tsingshan secured bank credit to honour its margin calls, stopped as soon as it started on March 16 due to a software glitch. Another glitch the next day delayed trading by 45 minutes, with various price limits put in, before contract orders started trickling in.

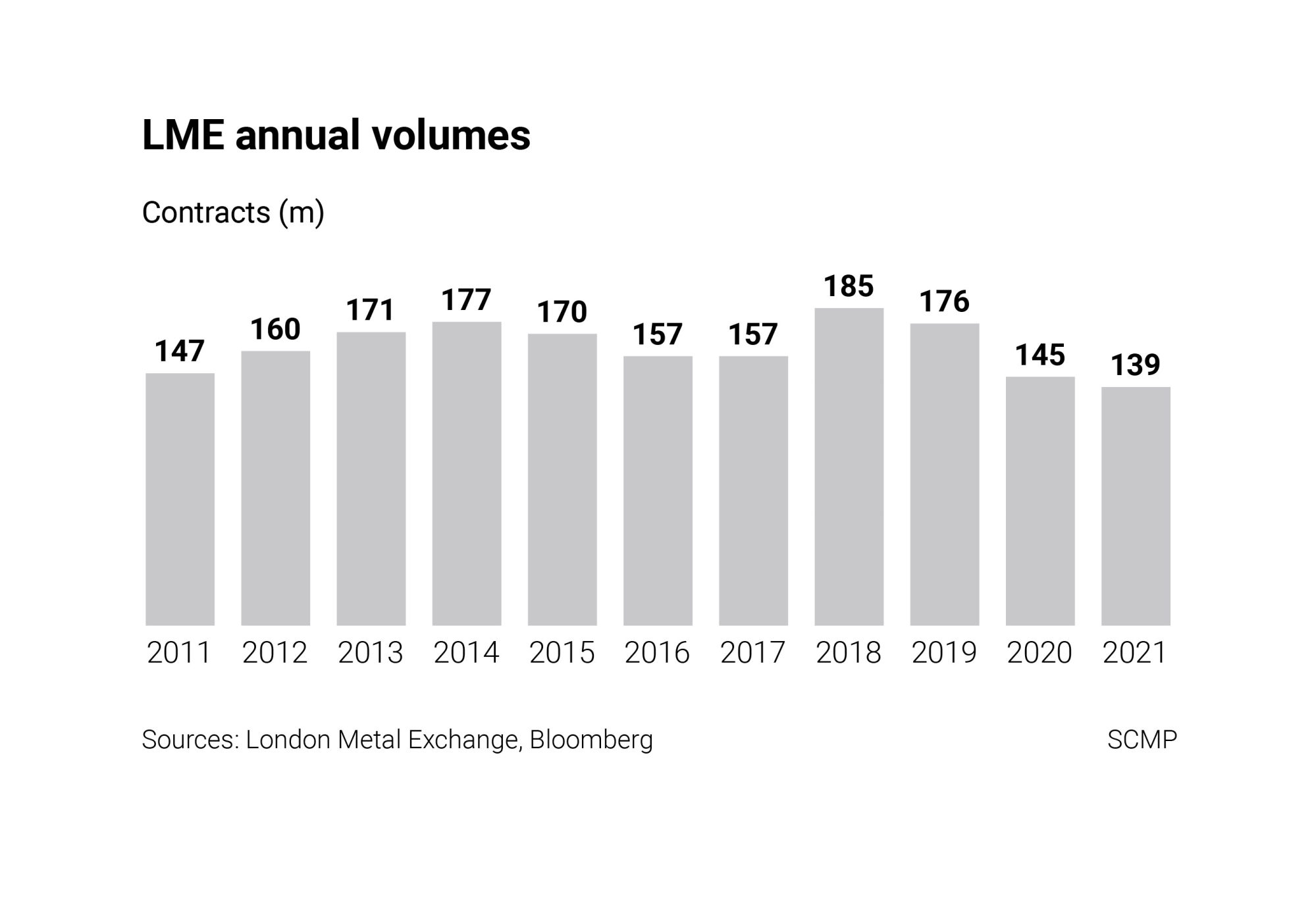

Nickel contracts now change hands at a fraction of their daily average volume over the past year, raising the question whether the LME – with its quaint rituals – is still reliable in setting the prices of metals such as aluminium, copper, nickel and zinc. Mainland China, the biggest worldwide consumer of industrial metals, is already offering a trading venue in Shanghai.

“They put themselves in a situation where they had a choice between several very, very bad decisions,” said Mark Thompson, a veteran trader and the executive vice-chairman of the mining development firm Tungsten West. “They took the worst of those bad decisions in cancelling trades, which effectively sounded the death knell for the LME. People have just given up on the LME, and I think this is going to continue.”

Chamberlain, a former UBS banker who advised HKEX in its £1.4 billion (US$1.8 billion) purchase of LME, joined the metals exchange in 2012 as its head of business development before being promoted to CEO in 2017.

Since then, he has reformed the LME’s warehousing system for metals and made the trading system more attractive and accessible to hedge funds and other investors. He reined in some of the behavioural excesses among traders, banning alcohol consumption during the workday and stopped companies from hosting LME Week-branded events at strip clubs and casinos.

Chamberlain, 39, even tried to take his hatchet to the LME’s open outcry ring, where traders use hand signals and shouts to transact different metals in five-minute chunks throughout the day. Traders pushed back, reluctant to abandon the final bastion of the open outcry, arguing that the rituals are necessary for complex trades and help protect mining companies from wild swings in commodity prices.

Russia accounts for 5 per cent to 6 per cent of the world’s nickel supply and nearly a fifth of high-quality nickel, according to a research report by the Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

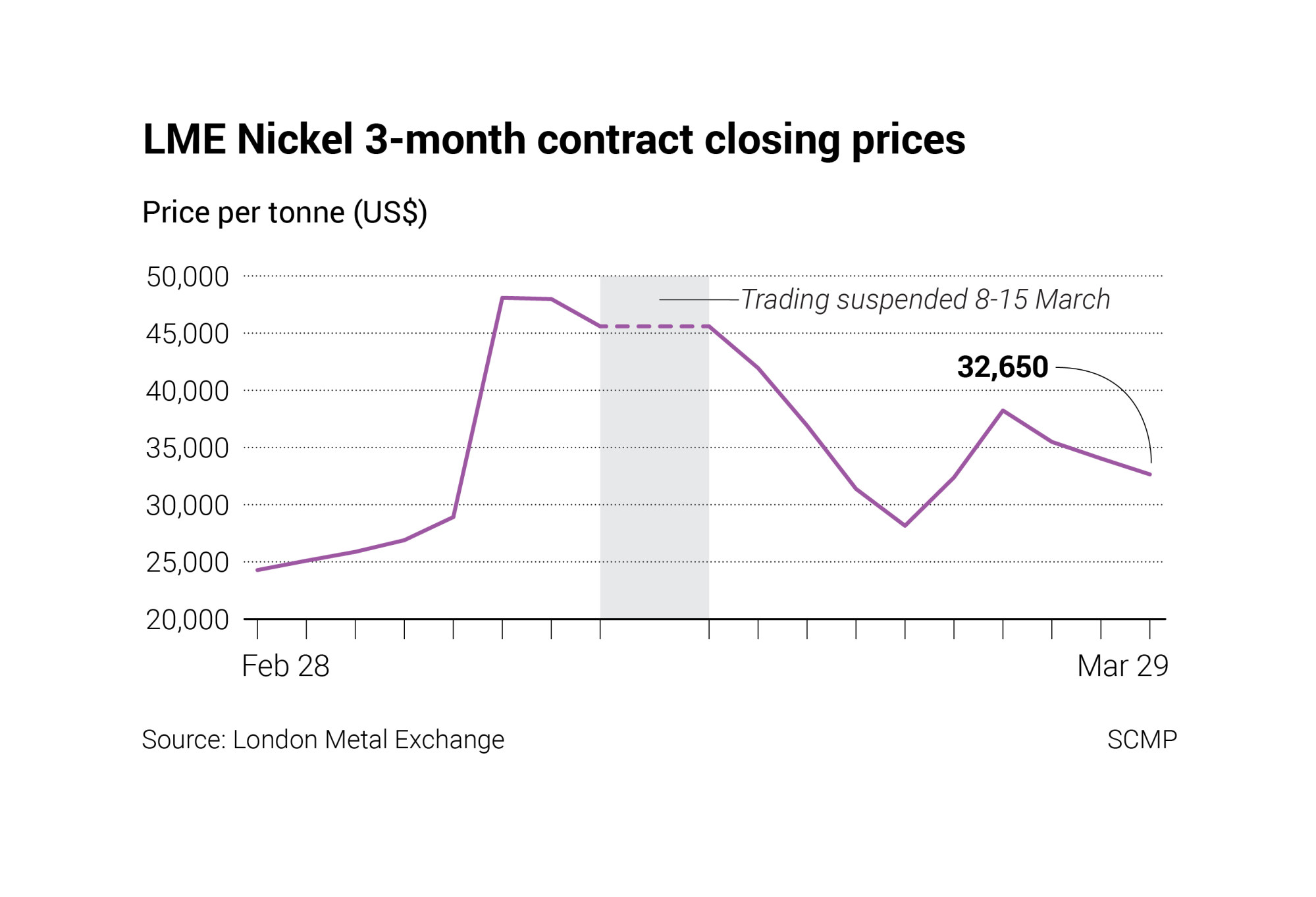

Nickel, which traded between US$22,750 and US$25,260 a tonne in February, briefly topped US$100,000 a tonne during the Asian trading session early on March 8.

The sudden surge squeezed nickel producers, who often short-sell contracts of the metals they work with as natural hedges against volatile costs. The squeeze left Tsingshan and their brokers with a dilemma: deliver the metals on their contracts, or pony up more capital to cover their margins.

Xiang was hardly the only short seller facing the squeeze. The nickel rout put pressure on other metals, raising the spectre of a systemic risk to the market. The LME halted trading of nickel and cancelled all transactions in the metal made on March 8.

When trading reopened eight days later, the LME put in price limits that were the equivalent of “circuit breakers” in the equity market. Nickel prices could move no more than 5 per cent above or below the prior’s day closing price.

Electronic trading was suspended within minutes of opening on the first day back because some trades were erroneously allowed to enter below the price limit. The following day, the opening was delayed by 45 minutes because of another glitch.

Trading continued after the daily price limit was raised to 15 per cent after complaints from traders about paltry liquidity. The suspension and chaos sparked threats of lawsuits by some investors and calls for regulatory intervention.

“I absolutely don’t want to understate what a challenge this is and the work we have to do to restore confidence around nickel,” Chamberlain said in a telephone interview from his car last week. “It is equally important to note that there are other metals. I think the market has worked very effectively in these difficult times.”

Still, the controversy has raised questions whether Chicago or Shanghai could play a bigger role in global metals trading.

While transactions closed for more than a week in London, nickel kept trading in Shanghai, providing the de facto measure for companies looking to set prices for over-the-counter contracts of the metal.

China is about to relax its markets to let qualified foreign investors (QFII) trade commodities in Dalian, Shanghai and Zhengzhou, giving the nation a larger role in global finance and internationalise the yuan.

Shanghai is the only place where foreign investors can trade nickel in China, but the futures market for the metal is much smaller, with only half the daily average volume of London.

Investors are allowed to trade monthly futures contracts of as little as a tonne of nickel in Shanghai, with a minimum price fluctuation of 10 yuan (US$1.58) a tonne. The daily price limit is set at 4 per cent above or below the settlement price from the prior day.

By comparison, the LME offers six-tonne lots, with a range of time frames from futures to cash settlement for immediate delivery. The three-month contract is the most widely followed and the daily price limit is 15 per cent above or below the prior day’s closing price.

In addition to the contract size, trading by foreign investors in Shanghai’s nickel market remains limited because of the need to trade in yuan and the requirements to be registered as a qualified foreign institutional investor (QFII) in China.

To trade in commodities in China, overseas traders must show financial soundness, good credit records and experience in securities and futures investment. They also have to apply via a domestic custodian before they can open an account, which can take several months for approval.

Others have questioned whether the HKEX is the right owner for the LME.

Adam Cochran, a partner at the activist fund Cinneamhain Ventures, said on social media that it appeared “political pressure” was being exerted by Beijing because of Tsingshan’s massive short position, without offering evidence.

Thompson, the Tungsten West executive, said he is not convinced the HKEX will still own the LME within two years’ time.

“They are either going to be in charge of an institution that continues to fail under their ownership, and they just need to get out, or there may be things that come to light in the litigation process that brings into question their fitness to own and operate a recognised investment exchange in London,” he said.

The HKEX bought LME to expand ties between Western economies and China, the biggest global consumer of metals. The move was also aimed at diversifying the HKEX’s revenue from the local stock market’s turnover and new listings.

“The LME sought to act in the interests of the market as a whole and took these decisions with full regard to the regulatory process,” the HKEX’s chief executive Nicolas Aguzin said on March 29 in Hong Kong, adding that the LME would continue to manage its business independently. “While the situation we saw in nickel was unprecedented, we’re committed to learning lessons from these events to prevent situations from happening in the future.”

Despite the fanfare, Hong Kong barely registers in global commodities trading. A dozen LME metal contracts, including two for nickel, regularly count among the least-traded futures contracts in Hong Kong since their debut eight years ago.

Chamberlain, who is due to leave the LME on April 30 for a job at a digital-asset custodian service, said the HKEX has been a “very supportive and very sensitive” shareholder and understands the need for decisions to be made in London.

“This clearly has been a reputational challenge for the LME. There’s no doubt about it. The future will depend on how we respond,” Chamberlain said. “We’ve always been conscious of the competitive threat from other markets.”

“We have very able and agile peers,” he said. “All we can do is to do our best to rebuild the nickel market confidence and we’ll be judged by the success of that endeavour.”

Additional reporting by Enoch Yiu in Hong Kong