Breaking up HSBC: Ping An’s call to debate the future of Hong Kong’s largest bank raises vexing question if its value is greater than the sum of its parts

- Ping An, HSBC’s biggest shareholder, making push for change at the lender in latest example of investor strife

- Asia is the bank’s biggest profit centre, but insiders say much of its revenue in parts of its Asian business originates outside the region

HSBC’s decision in 2020 to scrap dividends infuriated the bank’s legion of Hong Kong shareholders from retirees to pension funds who depend on regular payouts by the city’s largest currency-issuing bank for income.

One such retiree was Lo Chi-man, 71, a shareholder for 12 years who counted on the 6 per cent average dividend on his 50,000 shares to supplement his pension. He sold his stake when HSBC acceded to a call by the UK banking regulator to suspend payouts and conserve capital for the unfolding Covid-19 pandemic.

“We want shareholders to participate in the debate and to propose solutions for HSBC,” a Ping An spokesperson said this week, days after the bank reported a 28 per cent plunge in first-quarter profit. “Ping An supports all reforms and proposals from investors that can help HSBC’s operations and long-term growth.”

“From a pure business point of view, [a break-up] wouldn’t make sense,” said Hugh Young, the Asia chairman of Abrdn, which owned 1.3 per cent of HSBC as of March 31. “It would make senseif they just found life politically far too difficult to squeeze, between China and America. Do they just give up the ghost? The raison d’être for the bank has been to bring the East and the West together.”

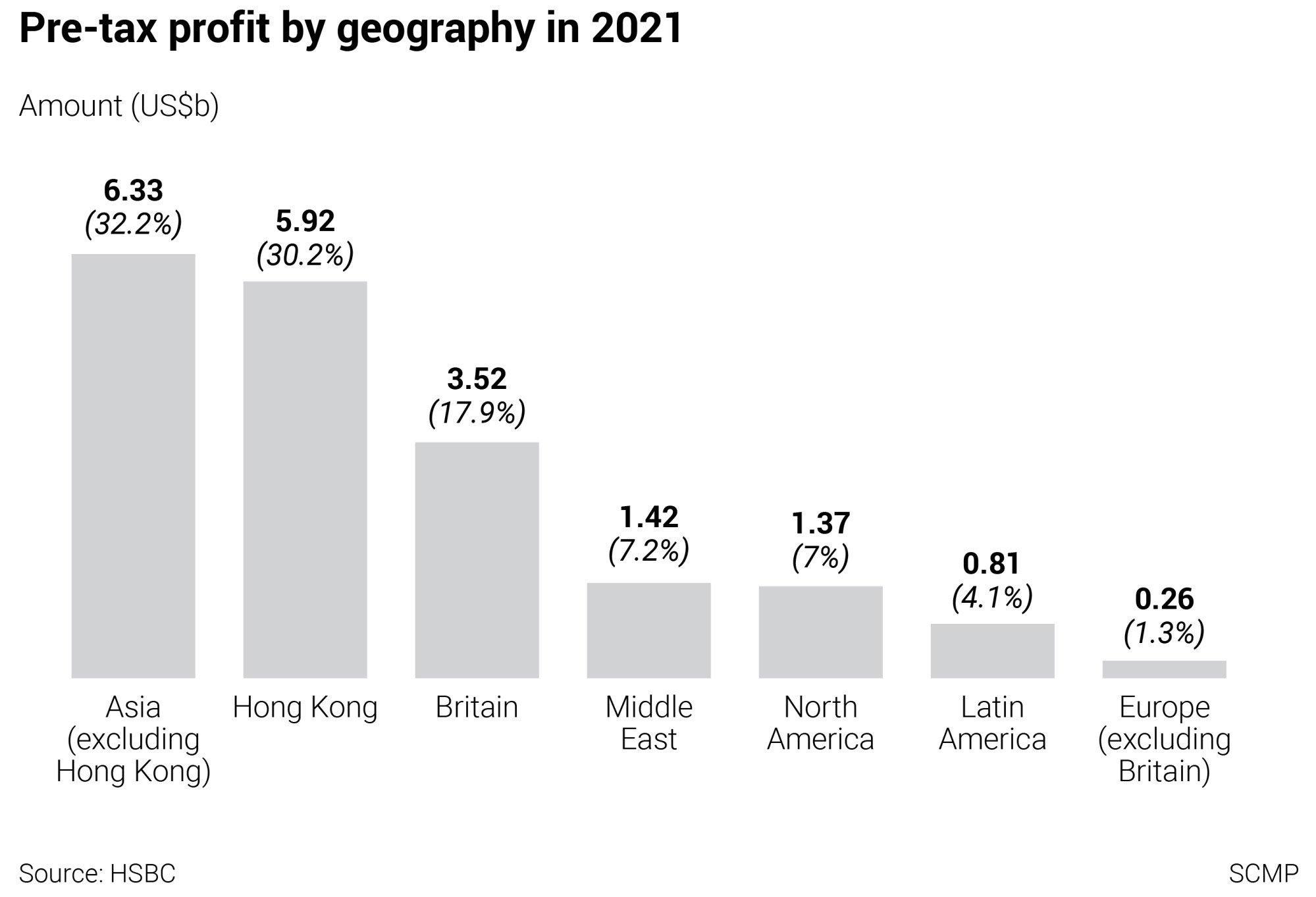

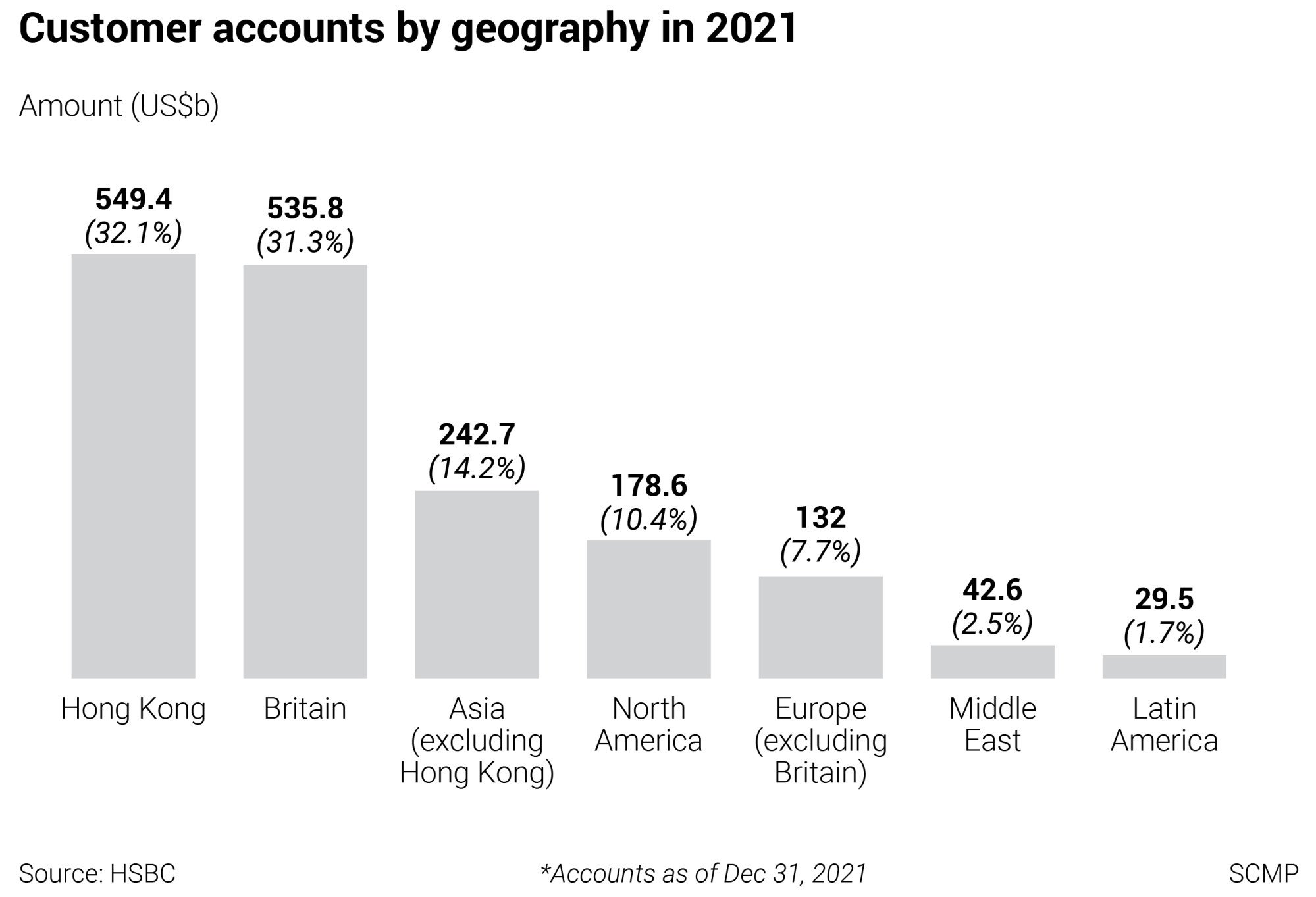

HSBC has been headquartered in London since its takeover of Midland Bank in 1992, which subjects it to UK regulations, even if it traces its roots to 1865 in colonial-era Hong Kong and Shanghai, and earned two-thirds of last year’s pre-tax profit in Asia.

“If HSBC splits its Asia operations and moves its headquarters to Hong Kong, it can escape the need to follow UK regulations that are not in the interests of Hong Kong investors,” said Sai Kung’s district council member Christine Fong Kwok-shan, who represented more than 500 local shareholders opposed to HSBC’s 2020 dividend suspension.

HSBC’s shares jumped by as much as 4.5 per cent in Hong Kong since Ping An made its first public comments on the situation this week. The stock has outperformed Hong Kong’s benchmark Hang Seng Index since the start of 2022, as well as rivals such as JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

HSBC’s shares are still trading 43 per cent lower than their most recent high in January 2018, down 18 per cent since its latest “pivot to Asia” was announced in February 2020. That has added further fuel to discontented shareholders pushing for a change.

Ping An, which does not hold a seat on HSBC’s 13-member board, is understood to have cited Prudential’s spin-off of its European and US insurance businesses to focus on Asia as an example of how HSBC’s break-up could benefit shareholders.

Still, Prudential’s shares have fallen 48 per cent in Hong Kong since January 2018, and have declined by 44 per cent since it completed the spin-off of Jackson Financial in the US last September.

Many of HSBC’s peers have not done much better. Crosstown rival Standard Chartered’s shares have fallen 42 per cent since January 2018 in Hong Kong, whilst shares of British rival Barclays have declined 23 per cent in that same period in London. Shares of much smaller Singapore rival DBS have risen 24 per cent in that period.

“While we are not sure if a break up of HSBC would improve its profitability, it is worth having a review,” said Tom Chan Pak-lam, chairman of Hong Kong Institute of Securities Dealers. “HSBC’s Asia business is the most profitable area of the bank. If it lists its Asian business as a separate entity, it is more focused and has a clearer structure.”

Ping An could force a vote at an extraordinary general meeting, but is not expected to do so at this time.

The latest shareholder push to split HSBC raises the question whether the bank is greater than the sum of its parts. Dismantling HSBC requires the bank to navigate a variety of complex challenges, from its capital structure to the disenfranchisement of UK shareholders who are not mandated to own Asia businesses, analysts said.

HSBC stands apart from other rivals in Asia and around the world with its broad reach, combined with deep and long-standing ties in China, insiders said. Splitting that into pieces would remove the unique proposition it can offer clients.

Chief executive Noel Quinn has placed greater emphasis on Asia in recent years as part of HSBC’s latest strategy revamp, shifting several global business leaders to Hong Kong and billions of dollars in capital to the region.

Nearly half of the revenue booked in HSBC’s Asia investment bank last year came from outside the region and 77 per cent of its global wholesale banking revenue came from international relationships across its footprint.

“HSBC is the world’s leading trade bank and some companies may prefer a UK-regulated bank to one potentially subject to Chinese influence,” BofA Securities analyst Alastair Ryan said in a research note.

At the same time, the bank has issued debt that requires it to be regulated in London, another challenge to unwinding its operations. The lender is reluctant to relocate its headquarters again, after last conducting a review in 2015.

“We think we’ve got the right strategy,” HSBC’s chief financial officer Ewen Stevenson said during a media call last week, adding that executives are “not considering” a break-up of the bank. “If we can deliver that strategy, it [means] a material amount of upside to returns and shareholder value. I think we’re seeing that in the share price. We’re broadly one of best performing bank stocks globally over the last year.”

The calls to break up come at a seminal moment for Quinn, the long-time HSBC insider who took what some have described as the most difficult job in banking three years ago.

Quinn, who ran HSBC’s Asia and global commercial banks before becoming its top executive, had to navigate a string of controversies since stepping into the job, while auditioning in an interim role for seven months initially as the lender flirted with hiring an outsider as leader for the first time in its 157-year history.

China has HSBC in a vice over Hong Kong’s new security law

Despite the challenges Quinn faced in his first three years as CEO, HSBC executives are confident about the bank’s prospects, as global central banks raise interest rates in the coming months, which improves profit margins for banks.

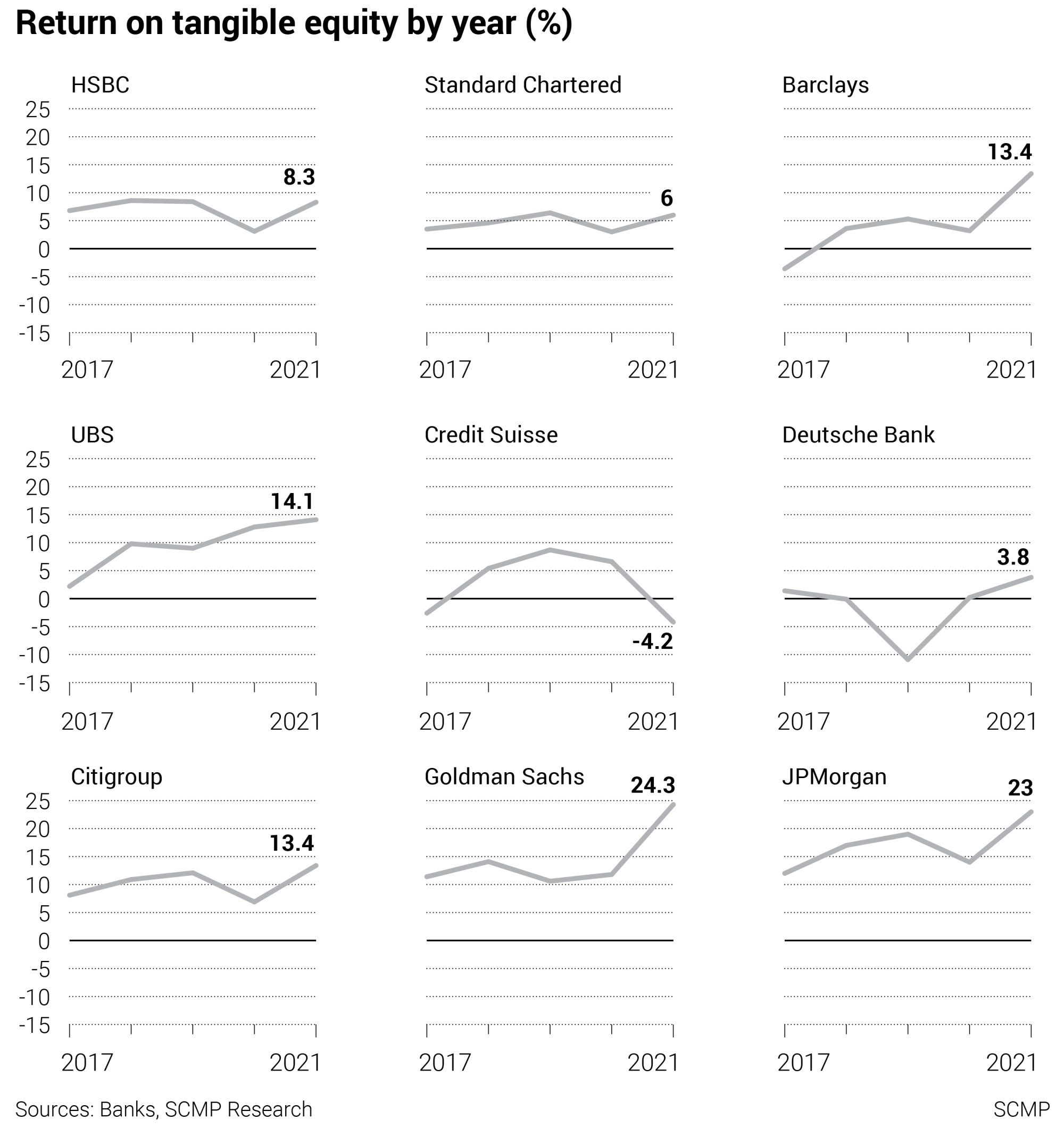

HSBC expects to reach double digit returns on average tangible equity by next year as a result of interest rate rises and as Hong Kong eases severe social distancing measures. Its annualised return on average tangible equity stood at 6.8 per cent in the first quarter.

Against this backdrop, Quinn is doubling down on the long-term prospects of rising incomes in Asia, shifting more than US$6 billion in capital from underperforming markets in the West to the region over a five-year period and going on a hiring spree.

The bank sold its retail banking operations in the US and France, increased its stake in its China securities and insurance ventures and bought retirement businesses in Singapore and India.

As the biggest foreign bank in China and the largest lender in Hong Kong, HSBC is better positioned than its competitors to capitalise on trade flows, as well as the growing wealth of Chinese customers onshore and outside the mainland, Quinn said.

“International connectivity remains key to our strategy,” he said last week. “The benefits of our scale and our international network increasingly differentiate us from domestic or regional peers.”

All these projections and Ping An’s push came too late for Lo, who sold his HSBC stake, and said he would not return as a shareholder.

“The suspension of dividends forced me to reduce my living standard because I lost my regular income,” he said. “It did not fit with my investment purpose, and I was very disappointed.”

“I do not think HSBC executives will listen to Ping An,” he said. “Many loyal shareholders like me have called on HSBC to move back to Hong Kong, but they never listened to us.”