Is Britain’s new investment law a hostile act to escalate the global technology war with China?

- Recently enacted National Security and Investment Act has given the British government the ability to block more deals on national security grounds, similar to the US

- Business Secretary Kwasi Kwarteng has used new powers to block deals by Chinese and Hong Kong companies. He is also reviewing other China-linked transactions

More than a year ago, the Dutch semiconductor maker Nexperia took full ownership of Britain’s largest, home-grown semiconductor producer Newport Wafer Fab, after agreeing to buy the remaining stake it did not own for £63 million (US$75 million).

Nexperia, with more than 14,000 people on staff globally, proclaimed the purchase of financially strapped Newport and its 500 employees as complementing its existing manufacturing sites in the United Kingdom and in Germany and as a key cog in expansion plans to meet the “growing global demand for semiconductors.”

The Newport takeover is one of several high-profile deals now caught in limbo under a law enacted earlier this year that gave the British government powers similar to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) to block foreign takeovers, including the ability to retroactively end such deals.

“The expectation is that the government will be more likely to intervene in transactions under this new regime,” Glenn Hall, a partner at Nelson Rose Fulbright in London said in a recent client note.

“The vast majority of transactions reviewed under the new regime are expected to be cleared without needing remedies,” Hall added. “Despite this, the new regime is far-reaching with serious consequences for non-compliance and requires parties to transactions in a much wider range of situations to engage with a potential national security review than under the previous Enterprise Act regime.”

The legislation, which replaced the national security provisions of the Enterprise Act, gave British officials more power to review a broad range of transactions, including minority investments, acquisition of voting rights and acquisition of assets, including intellectual property.

As part of the new rules, acquirers in 17 sensitive economic sectors, including advanced robotics, artificial intelligence and data infrastructure, are required to notify the government about significant transactions for review. Failure to do so could result in criminal and civil penalties and having the transaction voided, up to five years later.

Will Britain join the US in banning Chinese camera makers Hikvision, Dahua?

“The new regime adds an additional level of friction in global deal making, as an increasing number of transactions [including certain internal reorganisations] require UK government approval before completion,” said Michele Davis, a partner in the global antitrust and foreign investment team at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer.

However, it is not the only nation to do so, with more than 100 countries now having “some form of investment laws”, Davis said.

The Royal United Securities Institute (RUSI), a British defence and security think tank, warned earlier this year that the law could introduce greater barriers to doing business in Britain, making it a “a less attractive – or at least less straightforward – place to invest”.

“The legislation should provide safeguards against potentially malicious investors,” Alex Carlile, a member of the House of Lords and a distinguished fellow at RUSI, wrote on the think tank’s website in May. “But for some companies, the requirements of the act will add another layer of costs at a time when they already face high inflation and tighter purse-strings.”

Kwasi Kwarteng, the business secretary, has since used his new powers to block deals involving Chinese and Hong Kong companies and is reviewing other transactions involving Chinese and Australian buyers, including the Newport deal.

China firm reveals geopolitical undertones in failed Pulsic purchase

Kwarteng’s office has also undertaken a separate national security review of a £4.2 billion acquisition of a 60 per cent stake in National Grid’s natural gas transmission business by a consortium led by Australia’s Macquarie, the world’s biggest infrastructure investor.

Kwarteng’s office has pledged to take a special share in the Sizewell C nuclear power plant in Suffolk on England’s east coast and, alongside French firm EDF, is seeking additional investors to replace funding from China General Nuclear Power as a partner.

Lawyers said the NSIA’s review process is “agnostic” when it comes to particular countries, such as China.

However, acquirers in sensitive sectors need to consider the potential outcomes of a review, particularly if “the acquirer may raise risks in the eyes of the UK government”, said Davis, the Freshfields partner.

The US has long used CFIUS to restrict the sharing of dual-use technology or block deals in sensitive industries, but a shifting geopolitical landscape and rising tensions over trade and technology with China has seen an expansion of the regime and heightened scrutiny of deals with China links in the US and elsewhere globally.

Will expanded US review throw the baby out with the bathwater?

In June, the European Commission reached an agreement with the EU’s member states to allow it greater power to block deals or issue fines for foreign-backed takeovers with annual revenue in the EU of €500 million (US$509 million), as well as government contracts worth at least €250 million. China’s expansion was a key point in the debate.

Amid rising geopolitical tensions and ongoing logistical issues British businesses are actively rethinking their supply chains in China and elsewhere to “safeguard delivery and enhance resilience”, according to the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), a trade group.

“In a globalised economy, and with China so heavily integrated into international supply chains, it’s only natural to take stock of how those existing links are performing and seek greater diversification where required,” said Andy Burwell, the CBI’s international director.

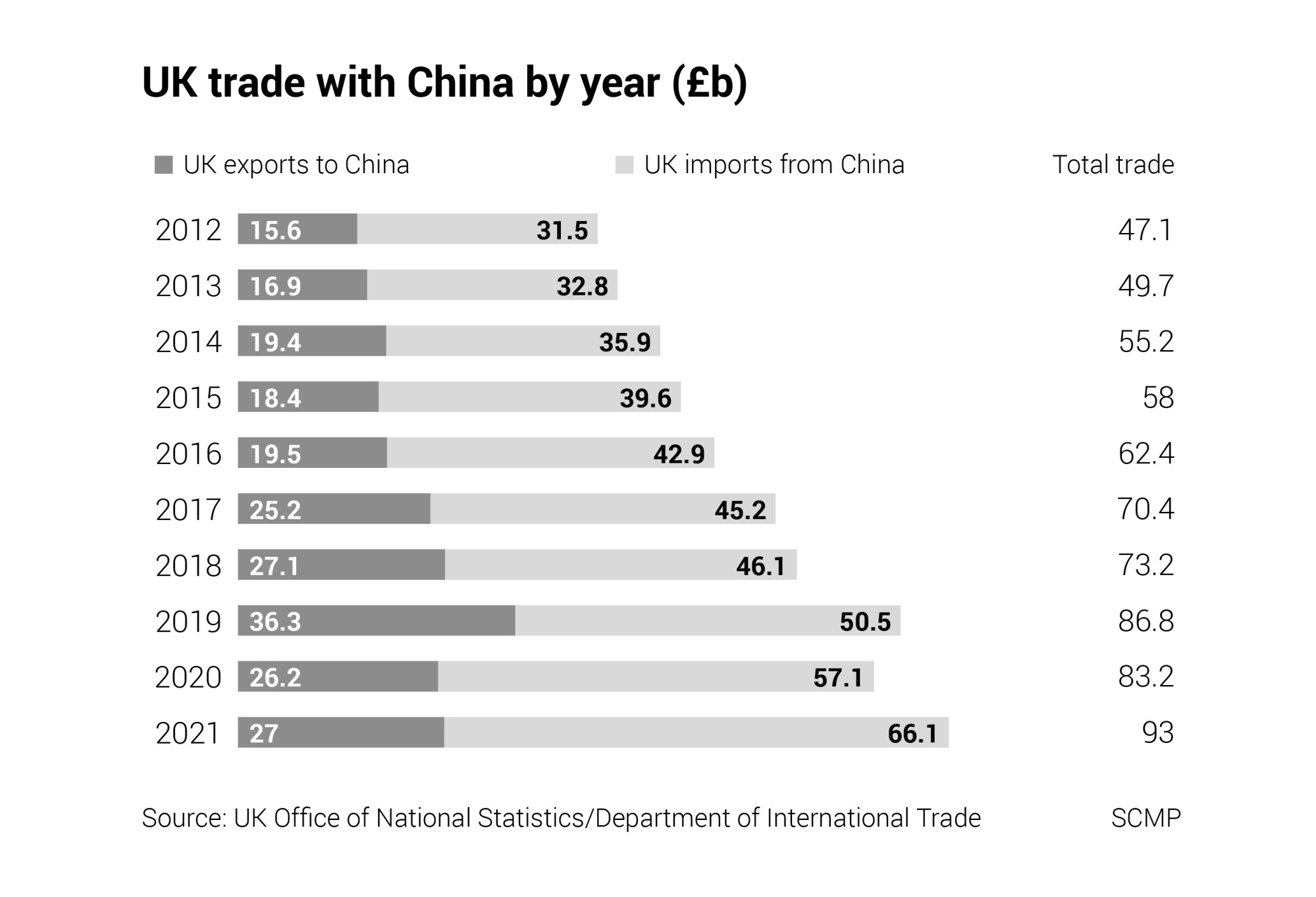

China was Britain’s third-biggest trade partner, accounting for about 7 per cent of all commerce in the 12 months ended March 31, according to the Department of International Trade. China accounted for £93 billion in total trade with Britain last year, nearly double the amount a decade ago, according to government data.

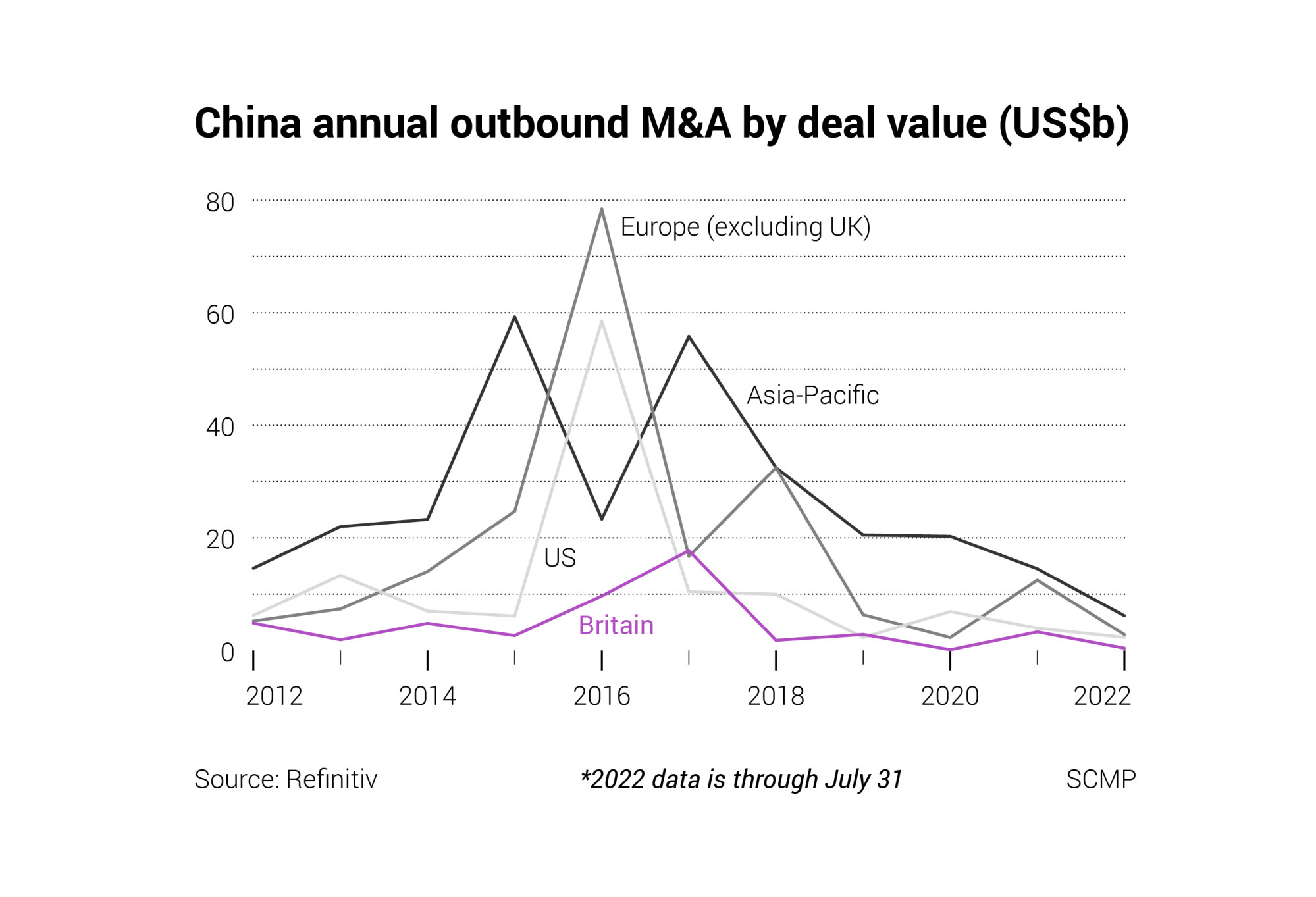

The souring relationship between Beijing and London also weighs on inbound deals from China, according to Refinitiv, a unit of the London Stock Exchange Group.

Chinese investments into Britain declined by more than four times to US$402.6 million from January to July, compared with the same period a year earlier, according to Refinitiv.

UK orders security review for Chinese takeover of chip maker Newport Wafer Fab

The slowdown in transactions came after Chinese investments into Britain had rebounded to US$3.3 billion in 2021, Refinitiv said. Transactions had slumped to US$125 million in 2020 as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

The growing distrust over Chinese-linked investment and delay in completing the Newport transaction is frustrating Nexperia, which has repeatedly asserted it is a Dutch-run company and has been forced to knock back speculation it would close the Newport facility and move its technology to China.

“We are not planning to shut any operations. We have been in the UK on the site in Stockport for more than 50 years; we have been in Hamburg for more than 50 years. We invested big time in Manchester; we invested big time in Newport,” Toni Versluijs, country manager for Nexperia UK said in testimony before a parliamentary committee in July. “We created the jobs. We are here to stay.”

Nexperia, based in Nijmegen of the Netherlands, has invested more than £160 million in Britain since 2021, stepping in as Newport was contemplating bankruptcy after struggling financially for several years. Nexperia had been Newport’s second-biggest shareholder since 2019.

“If you look at the facts around it, Nexperia saved Newport from bankruptcy,” Versluijs said. “We have secured the jobs over there. We also enabled the needs of the local cluster by providing an option to the previous owner to continue the aspirations of doing activities in compound semiconductors.”

Nexperia has called for the inquiry, announced in May, to be conducted “swiftly”, saying that its customers and employees are becoming increasingly impatient for clarity on the situation.

However, the uncertainty will last longer after the government extended its review last month, with a decision now not expected until mid-September.

“We look forward to a positive resolution to this matter as soon as possible, so that we can provide our staff and customers with certainty and continue our investment in the UK’s semiconductor industry,” a Nexperia spokesman said.