Why the early success of China’s supply-side reforms may not last

Beijing’s supply-side reforms, introduced a little over a year ago with the aim of eradicating idle capacity in heavy industry, were broadly welcomed as essential to securing China’s long-term growth.

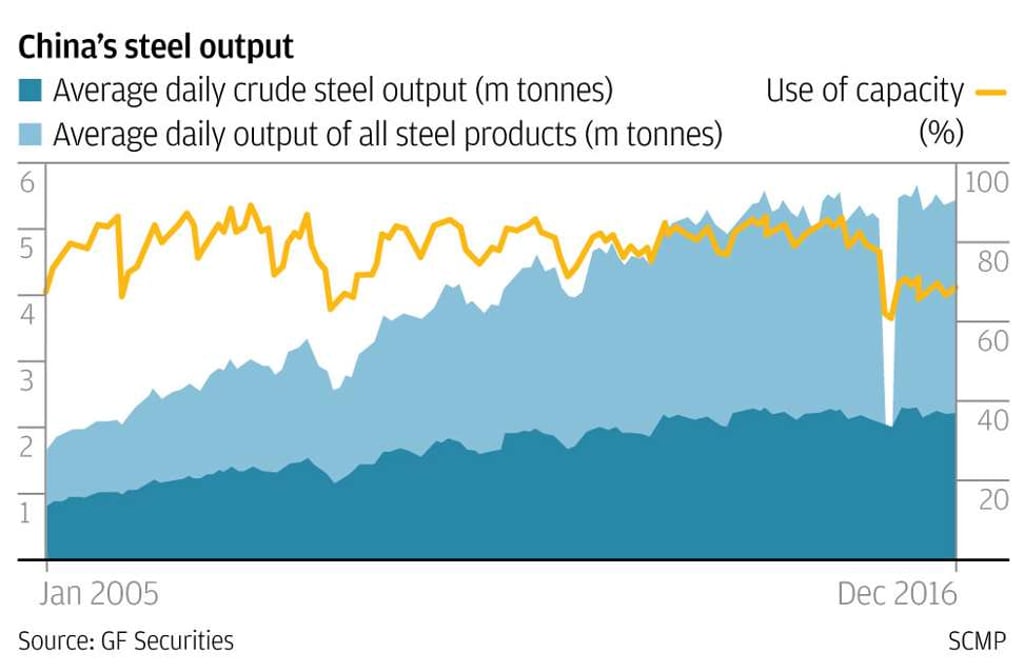

The coal and steel sectors, regarded as the economic backbone of the mainland, have been the major beneficiaries of the leadership’s efforts to retire obsolete capacities and cut excessive stockpiles.

And indeed, the new policy – backed by strict official targets – appears to be yielding the desired results. The prices of steel and coal shot up last year, and companies in both industries reported a marked improvement in performance.

“A stricter mechanism for punishing those disobedient local governments and steelmakers should be established to reinforce the long-term growth of the steel industry,” said GF Securities analyst Li Sha.

Addressing the National People’s Congress on Sunday, Premier Li Keqiang said the government will cut steel production capacity by 50 million tonnes and coal by 150 million tonnes this year. Observers and industry insiders will be listening intently for any further details on the future of Beijing’s supply-side reform policy.