China says renting is as good as owning a home, but how many will buy that argument?

The “go rental” underscores a multi-faceted strategy that involved allocating more land to rental homes, fostering professional leasing institutions and tax concessions

For city dwellers about to make the biggest purchase in their lives, the Chinese government has good news: renting is as good as owning.

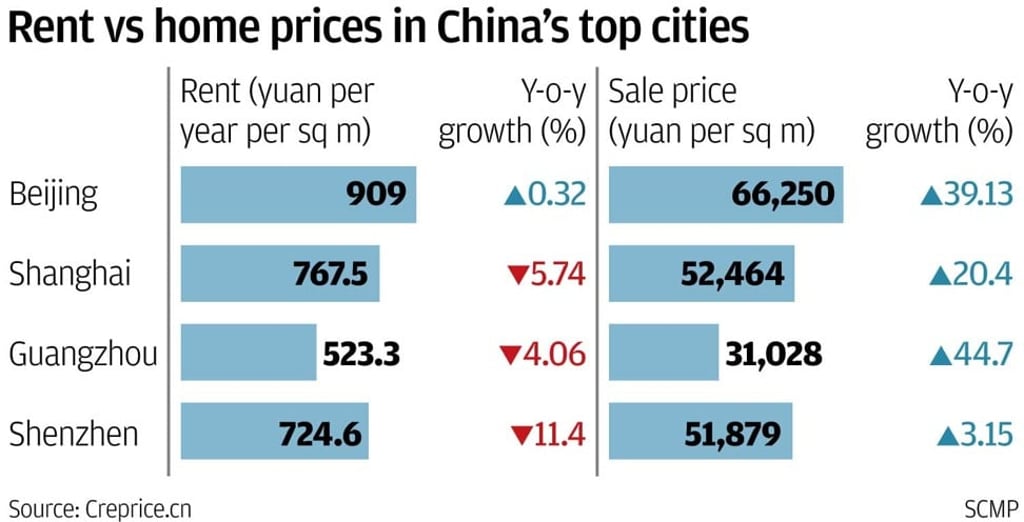

Anxious to cool an overheating home market during a year when the ruling Communist Party selects its next lineup of leaders, the authorities introduced a pilot programme in 12 major cities, where tenants of rental properties will enjoy the same access to public services as property owners.

Most importantly, they qualify to enrol their children in their neighbourhood school districts, thereby removing the need to buy property in areas with the best schools.

Nine ministries under the Chinese government cabinet issued a document on July 20, urging big cities with net population inflows to accelerate the development of the rental market. The right of rental tenants to enjoy public services will be written into law to ensure stability in the duration of tenancy contracts and rental income, while the pilot scheme is tested in cities including Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Nanjing and Xiamen.

“The law is part of a broader effort to address a missing piece in China’s housing market,” which is the rental market, said Yang Hongxu, deputy director of E-house China R&D Institute. “Several factors have made China a country with the high home ownership in the world, but not many people would settle on a tenant.”

The question is how far the latest experiment can go to take real effect, when it cuts into China’s household registration system, known as hukou. The hukou has its origins as the centuries-old family register, where a person is identified with the place of birth. The hukou influenced similar household registers in Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Russia, but is required by law in China and in Taiwan.