Exclusive | ‘Made in China 2025’: world’s biggest auto market wants to be the most powerful maker of electric cars

- This is the seventh instalment of a series on China’s industrial strategy to advance manufacturing

- Electric vehicles are as much as about helping China upgrade its manufacturing value chain as they are for reducing pollution

At the assembly plant of China’s leading electric carmaker, BYD, in the southern city of Shenzhen – and under the watchful gaze of a giant Transformer statue made of car parts – an electric car rolls off the production line every 90 seconds.

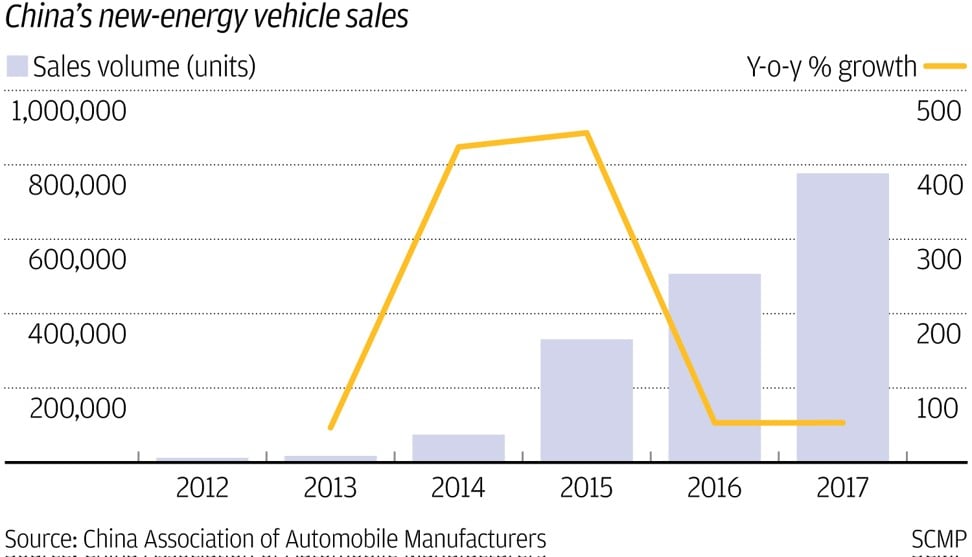

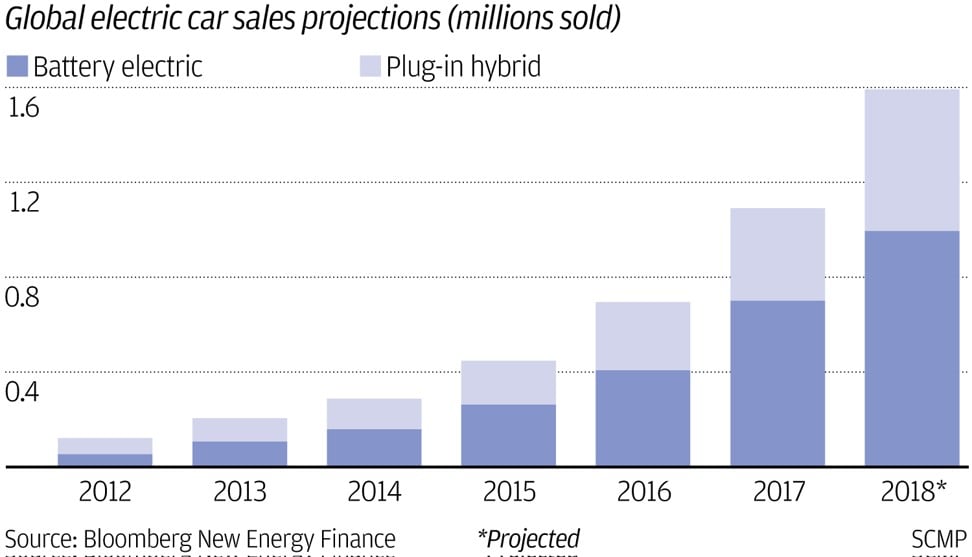

While US maker Tesla often grabs the headlines (though not always for its cars), BYD and peers like Beijing Auto and Roewe are quietly selling enough electric vehicles (EVs) to make China the world’s largest market for both electric and conventional vehicles. In fact, sales of EVs in China reached 770,000 units last year – more than half of all new-energy vehicles sold globally.

Driving the explosive growth is a government desire to promote the country as a world leader in green vehicles, and in their next incarnation as “smart” cars, in part because of serious pollution problems at home but also as a broader strategy to become a technological power in keeping with its global economic clout.

That vision is embodied in the “Made in China 2025” (MIC2025) industrial strategy, an ambitious plan first unveiled in 2015 to have the country catch up with global leaders and become self-sufficient in 10 core technologies, including new-energy vehicles.

“To become a world leader in terms of technologies is not an easy job,” said Peter Chen, a Shanghai-based engineer with US car parts maker TRW. “Given the huge market size in China, EV is certainly a key industry where the government wants to develop its own players to be world leaders.”

Shenzhen’s all-electric bus fleet is a world’s first that comes with massive government funding

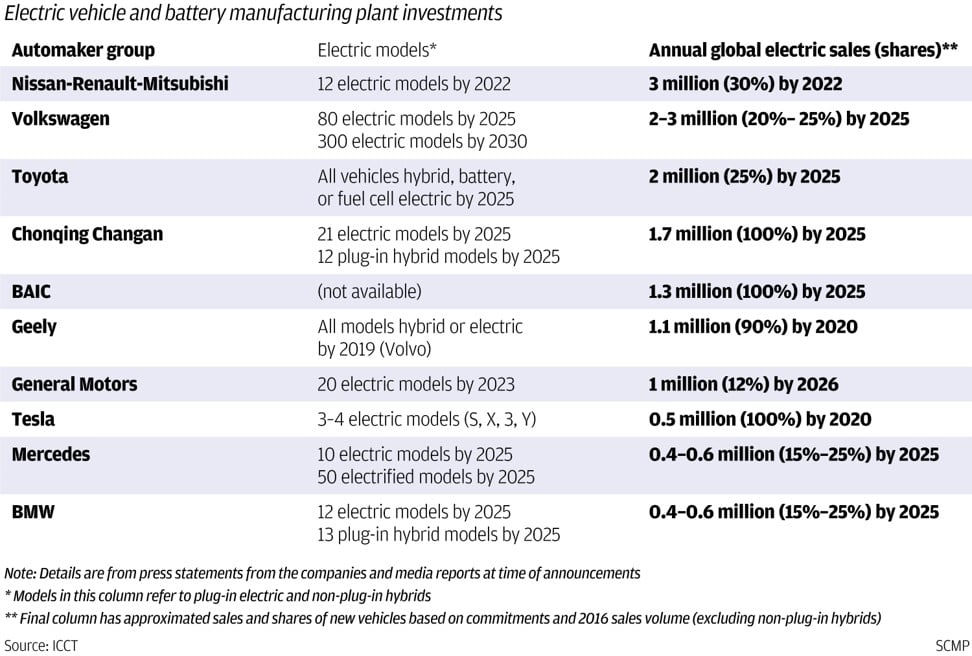

Under the MIC2025 plan, Beijing wants domestic carmakers to be selling 3 million EVs a year, making up 80 per cent of total domestic sales, while the top two EV makers would have 10 per cent of their total overseas by 2025, although it did not specify which companies.

Some of the more bullish industry executives predict that one-fifth of vehicle sales on the mainland, or about 6 million units, will be of green cars in 2023. BYD, meanwhile, the world’s largest new-energy vehicle maker by sales in which American billionaire Warren Buffett is an investor, sees itself as one of the leading “transformers” of the car industry.

Its chairman and president, Wang Chuanfu, foresees that all vehicles on the mainland would be electric ones by 2030, a forecast that may help the company achieve annual sales of one trillion yuan (US$144.4 billion) by 2025, or nine times its 2017 revenue.

To become a world leader in terms of technologies is not an easy job

The company sold 113,700 new-energy vehicles last year, a 13.4 per cent increase on the year before.

Even before the MIC2025 plan came along however, the industry had been given a boost by government financial backing in the form of easier access to funding, loosened oversight on overseas acquisitions and generous allocation of land for manufacturing, as well as subsidies for buyers and free driving licences.

The subsidies for buyers, first introduced in 2009, peaked in 2014 at 100,000 yuan (US$14,400), helping sales rise fourfold the following year.

They have now been cut to 60,000 yuan, pushing the price of a home-made EV to less than 100,000 yuan. However that is still around the same price as a regular petrol-engined car, although the running costs are cheaper.

As bold as Beijing’s vision is, however, catching up with the likes of Tesla and achieving the plan’s goals will not be easy.

Former premier Wen Jiabao had acknowledged as early as 2011 in an article in a Communist Party magazine that the development of EVs in China was rudimentary, with all the key technologies in foreign hands.

The Trump administration has used the plan as part of its justification for a series of tariffs it has placed on Chinese goods, sparking a trade war that has spooked companies and countries worldwide. There are no tariffs on Chinese-made EVs, but analysts cannot rule out the possibility of the broader trade spat affecting the sector.

Away from politics, there are other problematic areas. One is the huge investment needed.

There are also issues with battery technology that limit the range of domestically made EVs, as well as a lack of charging stations and questions over what happens when the government ends subsidies to buyers in 2020.

“Chinese EVs are still several years behind the global leaders in terms of technologies,” said Cao Hua, a partner with private equity group United Asset Management. “The limited driving range and the lack of charging stations are still the major stumbling blocks to the rise of China’s EV sector.”

Most of China’s indigenous EVs have driving ranges of below 300km (186 miles), compared to Tesla’s 500km (311 miles), because of battery limitations. Chinese-made batteries are relatively heavier and bigger than those of their foreign rivals because of the less sophisticated design of their cells. To make them lighter, Chinese makers have to cut the number of cells, thus reducing a car’s range.

The limited driving range and the lack of charging stations are still the major stumbling blocks to the rise of China’s EV sector

There are also safety concerns over domestically made batteries. At least five Chinese-made EVs, including vehicles by Chongqing-based Lifan Motors and Chengdu-based WM Motor, caught fire in August, according to media reports.

The ideal, and quickest, way for Chinese companies to advance their technological capabilities would be to get them from overseas via investment in or takeovers of foreign firms, said Cui Dongshu, secretary general of the China Passenger Car Association.

“It will be a trend,” Cui said. “Car-making is a strategically important sector where China needs to assimilate the world’s leading technologies and production to improve our own manufacturing capabilities.”

That, however, is not easy. Chinese officials have repeatedly acknowledged that core technologies are almost never for sale. The traditional and proven way has been to collaborate with foreign partners or to set up shop abroad to gain easier access to technologies.

“Chinese carmakers are enthusiastic about improving batteries to make better electric vehicles,” said Zhang Lihua, a vice-president with German car component company Webasto, which makes battery packs that provide electrical connectivity between cells.

“Many of them want to form a partnership with companies like us to support the development of their battery systems.”

Meanwhile Fujian province-based Contemporary Amperex Technology, which develops EV batteries and energy storage systems, plans to build a battery plant in Germany with an investment of 240 million euros (US$275 million) in 2022.

Another headache for EV drivers is the difficulty of finding a charging station. The country’s total of around 274,800 charging stations is well behind the number of electric vehicles sold in 2017, according to the China Electric Vehicle Charging Technology and Industry Alliance.

“Financial support to car and auto parts makers is not enough to establish a complete industry chain for EVs,” said Davis Zhang, a senior executive at Suzhou Hazardtex, an energy-solution provider to manufacturing companies.

“There is an urgent need for more concerted action between the central and local governments and car manufacturers to map out a plan for EV charging,” he said, adding however that power battles between different government departments and state-owned industrial giants were major obstacles.

One idea being discussed is installing charging piles at petrol stations across the country to turn them into public charging centres, but that requires the cooperation of China’s biggest oil companies and the power grid operators, and has yet to make any progress.

The question of what happens to EV sales when the subsidies are abolished in two years is also hanging over the industry.

Without the subsidies, the price of an EV could exceed 150,000 yuan (US$21,600), making it costlier than a petrol engine vehicle, while production costs of around 100,000 yuan per car mean makers could not cut prices too much.

“Worries about the cancellation of the subsidies from 2020 are heightening, and the question is whether the car companies can sustain sales without cutting prices to woo buyers,” said Nomura auto analyst Joseph Wong.

“Most Chinese EV makers will have difficulty making profits if the government stops offering subsidies.”

Speculation is also rife that local governments may stop offering free driving licences for electric car drivers. In Shanghai, private car licences cost nearly 100,000 yuan but are free to buyers of new-energy vehicles.

Finally, there is an enemy closer to home: competition.

The industry and information technology ministry this year required all carmakers, including joint ventures with foreign firms, to sell a minimum number of new-energy vehicles a year. To comply, a clutch of international companies including BMW, Volkswagen and Ford have established new ventures in China to focus on new-energy vehicles.

That would double the size of its global manufacturing and help lower the price of Tesla cars sold on the mainland, while also benefiting local firms who can become suppliers and learn from Tesla’s technology.

“The competition will be cutthroat as production volume jumps in the coming years,” said Nomura’s Wong. “Foreign brands will ratchet up pressure on Chinese home-grown brands as they are able to make better products.”

One way to get ahead in the EV race for Chinese firms may be to focus on “intelligent” electric cars, the next generation of green vehicles that use latest technologies such as artificial intelligence, GPS mapping and other functions to offer navigation, in-car entertainment and value-added services to drivers and passengers.

The sector has been made a national priority and a number of start-up tech firms are focusing on this area, including Nio, Xpeng, Pony.ai and Byton. Meanwhile BYD plans to launch its first self-driving cars within three years, in partnership with internet giant Baidu.

“Intelligent cars will dominate the streets by 2035,” BYD chairman Wang said at a Shenzhen forum in September. “BYD wants to plan ahead to embrace the digitalisation of the car industry.”

Others agreed that China’s increasingly tech-savvy youth will be one of the driving forces behind intelligent cars, and makers must pay attention.

“We are in a new internet era and it is time to build new generations of cars for Chinese millennials” said He Kun, a co-founder and chief executive of EV start-up DialEV. “They have different views as vehicles become electric and intelligent, and companies need to react quickly to meet their demands and make the right cars that are affordable for them.”