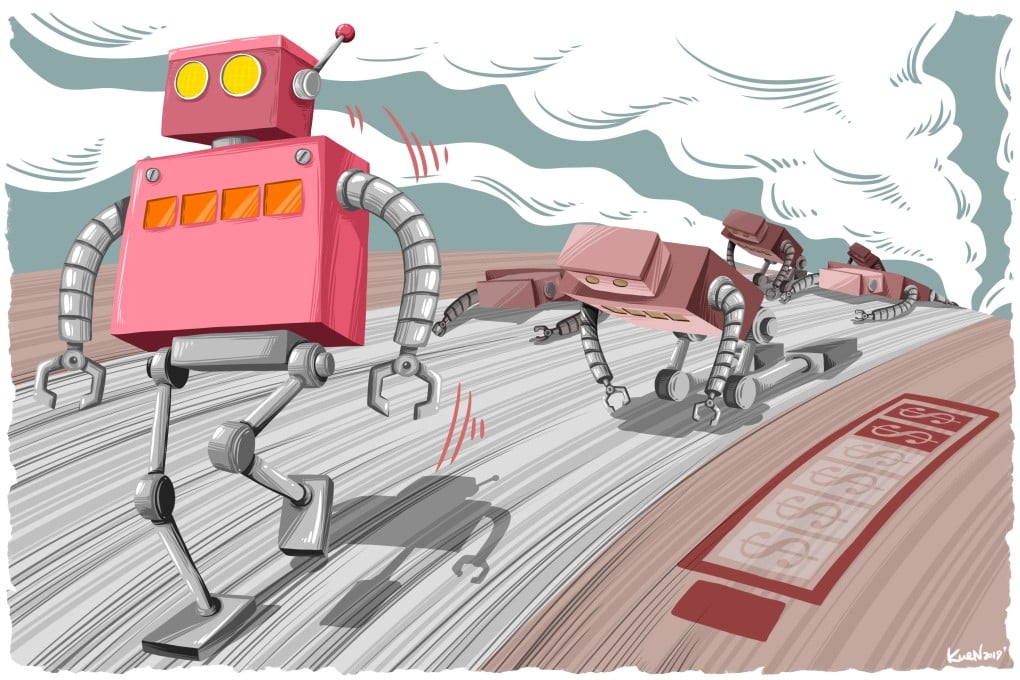

Chinese tech faces an innovation reality check as the economy cools and start-ups stumble

- Even after a banner year for venture capital funding, some investors predict that as many as 90 per cent of Chinese tech start-ups are doomed to fail

- The sheer size of the Chinese marketplace is no longer enough to keep a struggling tech company afloat

The slowing Chinese economy may be claiming some unexpected victims: without its robust engine, many tech start-ups relying on China’s fast growth for success are being cast out.

Despite healthy capitalisation, investors are finding that some companies’ underlying technologies may not be as innovative as hoped. And even after a banner year for venture capital funding in 2018, some investors predict that as many as 90 per cent of Chinese tech start-ups are doomed to fail.

“The market is going through a severe selection process,” said Weijian Shan, chairman and CEO of PAG, a Hong Kong-based equity firm managing US$30 billion. “Only those with true technology and an understanding of risk control are able to survive.”

The Chinese tech industry has impressed global investors since the dramatic rise of Baidu, Alibaba Group and Tencent in the past decade. Fearing missing out again, venture capital has been pouring into the younger generation of start-ups in hi-tech sectors such as e-commerce and financial technology, helping create a roster of Chinese unicorns – companies valued at more than US$1 billion – that dwarf those from other countries.

Alibaba is owner of the South China Morning Post.

Most Chinese start-ups had thrived, however, not because of cutting-edge technologies but through a business model that primarily built and sold everyday apps, from online payments to bike sharing, investors said.