Bank of China’s US$1 billion hole from plunging oil shows how investors and banks alike are ill-prepared for risks of chasing after high returns

- Bank of China’s Crude Oil Treasure product would ultimately burn holes in the pockets of the lender’s retail customers, estimated to total 7 billion yuan

- At least 60,000 people have invested in the product, according to Chinese media

Every day since April 15, David Wang's smartphone would buzz with a message from Bank of China. May contracts for Crude Oil Treasure, a structured financial product that gives the layperson an easy entry into the complex world of oil trading, was expiring in a week, and investors must close or roll over their positions, said the automated message.

Wang dismissed the warnings, and kept going long with 400,000 yuan (US$56,500) of his money at stake, believing that record-low oil prices offered him the chance of a lifetime to get into the market on the cheap.

“This is utterly disheartening and beyond any normal person's comprehension,” Wang said in the Shaanxi provincial capital of Xi’an by telephone, rueing a 1.4 million yuan loss from just two weeks of holding the investment, plus margin credit from the bank.

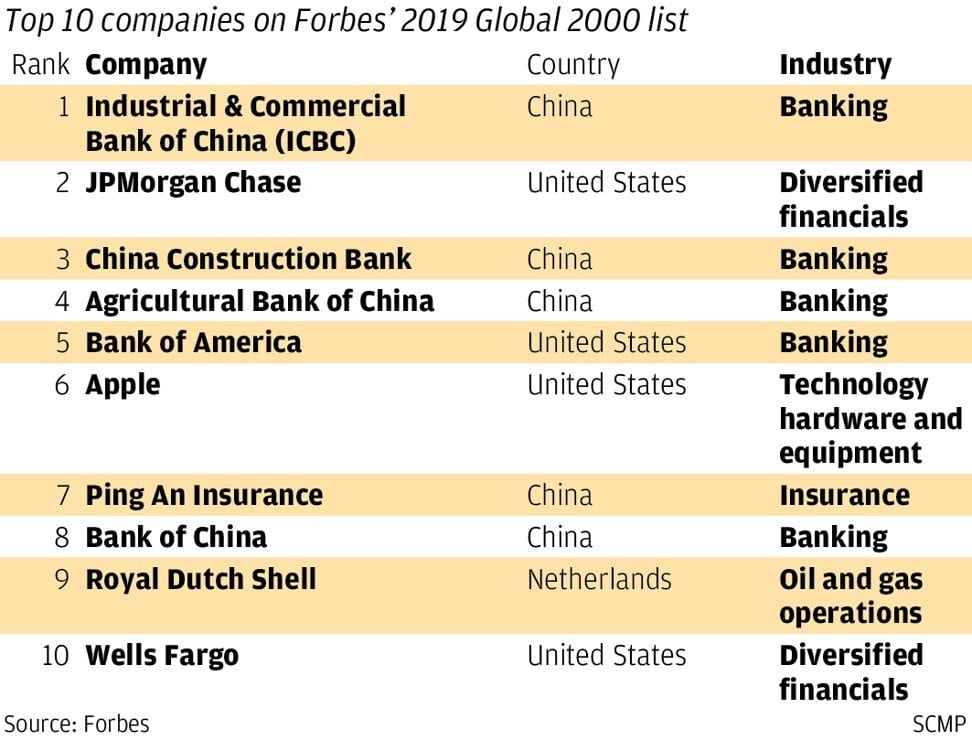

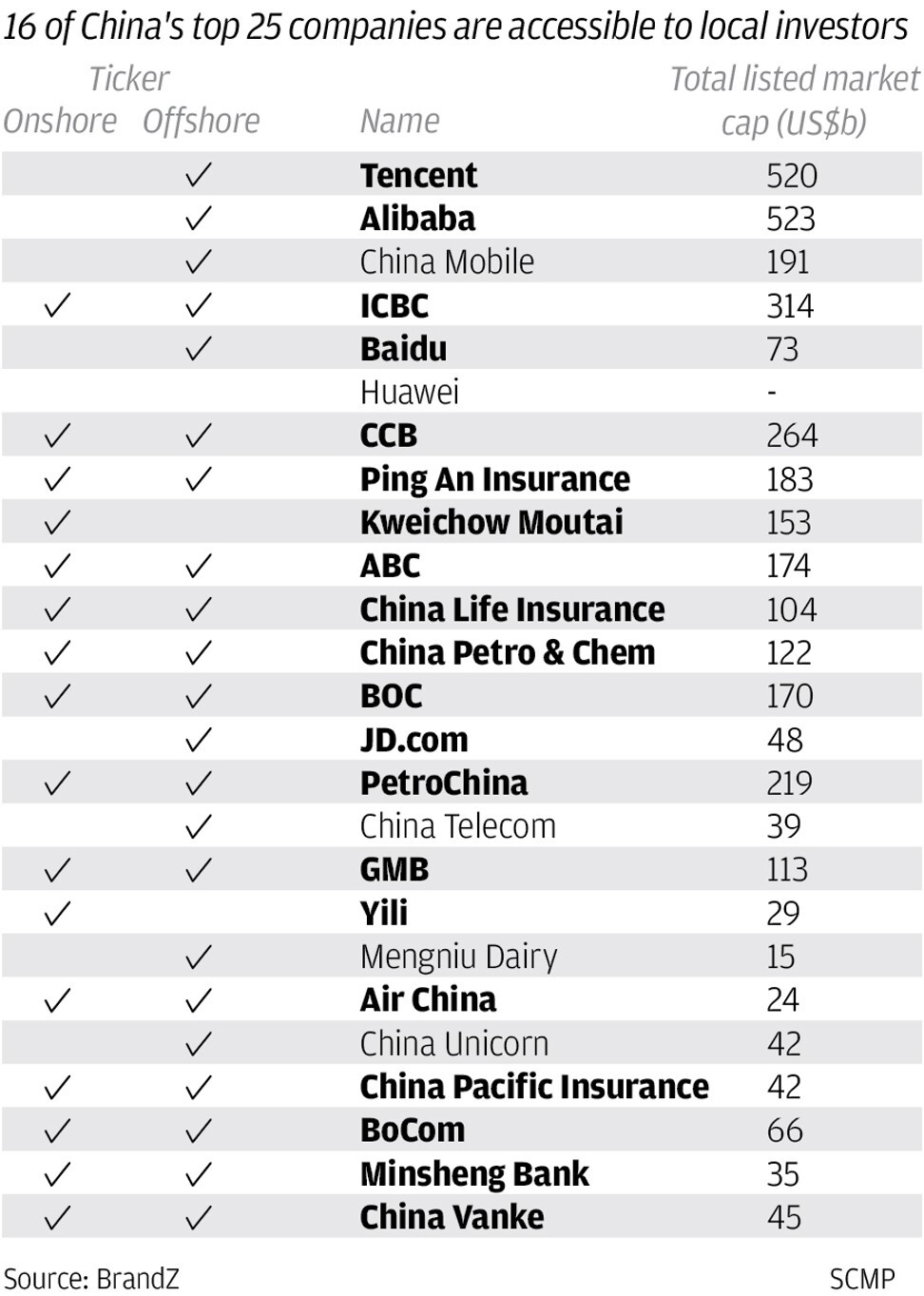

The brutal loss has far-reaching repercussions across China’s banking industry, as several of the country's biggest state-owned lenders – Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, China Construction Bank, Communication Bank of China, Shanghai Pudong Development Bank – have all hit the pause button on variations of the same structured financial product for their retail customers. The episode exposes the deficiencies in China’s 22.2 trillion yuan wealth management products offered by banks, where regulations and investor protection measures fail to keep up with an industry whose rapid growth had been amplified by technology.

“The incident has exposed the shortcomings of risk disclosures to retail clients and potentially insufficient or improper risk tolerance and products suitability assessments among Chinese banks,” said Lance Yau Tat-cheung, a dealing department manager of China Xin Yongan Futures.

For China’s banking industry, the fracas with oil futures is also its latest brush with risk in the nation’s journey toward market liberalisation and financial reforms.

As part of China's banking reforms, commercial lenders had been prodded and pushed to wean themselves off the fat margins between state-controlled lending and deposit rates that had sustained their growth and prosperity for decades.

For China’s government, the potential public grievance comes at a time when the nation is just emerging from three months of quarantines and work-at-home orders to contain the coronavirus outbreak. China’s legislature is scheduled to commence its annual meetings on May 22, after postponing the proceedings in March. The Great Hall of the People at Tiananmen Square, where the pomp and splendour of the meetings typically go on full display, is a mere subway stop away from Bank of China’s headquarters in Xidan.

Launched in January 2018, Crude Oil Treasure allowed customers to hold either long or short positions in oil contracts denominated in US dollars or yuan, where they can bet that the prices of WTI or Brent International would go up or down, all through a simple savings account at the Bank of China.

To make investments more accessible, the product subdivided the 1,000 barrels of oil associated with every WTI futures contract into units of barrels.

Investors must close their open positions before their contracts expire by buying or selling the same amount of contracts they sold or bought earlier. Alternatively, they can roll their positions to the next month by letting the trading system conduct the rollover based on the month’s settlement price.

The bank acts as the market maker, responsible for managing risks and generating prices based on factors including global oil prices, the renminbi’s exchange rate and market liquidity, it said in a product introduction on its website.

The product is for individuals with “a certain understanding” of the oil market, and have a “commensurate” level of risk tolerance, Bank of China said. It warned investors that they should understand the volatility in oil prices, as well as risks arising from various political and economic factors and global events.

Bank of China is “deeply disturbed” by its customers’ investment losses, according to an April 24 statement. Warnings about volatility and the impending expiry of contracts were sent every day since April 15 via text messages, phone calls, social media posts on WeChat and Weibo, the bank said.

“Had Bank of China acted faster, like one or two days before the WTI contract’s expiry, the losses would not have ballooned to this magnitude,” said Lin Boqiang, director of Xiamen University’s Centre for China Energy Economics Research. “Other banks have not had the same degree of problem as they have forced settlement of the products earlier.”

“Through products packaging and marketing, the futures nature of the underlying product has been downplayed,” said Yau of China Xin Yongan.

Different from standard investment products where investors entrust their money with a professional manager to invest, the Crude Oil Treasure is actually a platform on which investors can make buy and sell orders on their own, said Yang Zhaoquan, partner of Beijing Weinuo Lawfirm, retained by nearly 100 customers of Crude Oil Treasure with 40 million yuan in combined losses to sue on their behalf.

“It's against the law for the Bank of China to issue a product like Crude Oil Treasure,” said Yang, who has yet to file their suit.

Crude Oil Treasure is in fact a futures product even if it is being marketed as a tool for wealth management. Bank of China, despite being China’s largest global bank, is not licensed to provide futures products, he said.

Ant Financial Services, the affiliate of this newspaper’s owner Alibaba Group Holding, distributes a financial product on its Alipay platform by Southern Asset Management that tracks the price of crude oil and exchange-traded funds.

Customers applying to trade futures products at equity or futures brokerages would be subjected to more rigorous risk assessment questionnaires, and higher entry barriers, before they are allowed anywhere near their first transactions, said Yau of China Xin Yongan, the Hong Kong unit of mainland brokerage Yongan Futures.

Wang has allied himself with a dozen investors in representing about 200 Crude Oil Treasure customers in Shaanxi province to seek compensation from Bank of China.

They have visited the provincial offices of the bank, as well as the banking regulator, to demand for a revaluation of their holdings based on the April 15 settlement price, when they believe the bank should have informed them about the potential risks. Bank of China said it “handled the May futures contracts according to previous agreements,” in its statement.

“Given the nature of the market at the moment, it is clearly risky to leave it so close to the end, given some of the pretty well-flagged risk that storage capacities were approaching their limits globally,” said Sanford Bernstein’s senior oil and gas analyst Neil Beveridge. “Traders are squeezed when it approaches the contract’s expiry date.”

Emily Liu, a 35-year-old mechanical design engineer in Hangzhou, is among the hundreds of investors in Zhejiang province who are petitioning the regulators to bail out their losses. With 160,000 yuan in losses, Liu joined six chat groups on WeChat, each with about 200 members, with as much as 7 million yuan in individual losses.

For Wang, though, lessons have been learned the hard way.

“All hope is gone,” Wang said. “I hadn't been able to sleep and I have no appetite to eat since this happened.”