COP26: can China quit its coal habit while the world wrangles over climate goals and phasing out the ‘dirtiest’ fossil fuel?

- Coal produces nitrogen oxide, sulphur dioxide and carbon dioxide, the primary greenhouse gas and one of the main culprits of climate change

- Coal burning in open stoves and furnaces generate fine particles that hang in the air, leading to the notorious smogs of 1950s London, and Beijing

This second instalment of a four-part series on the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow looks at coal, and why it is shunned by environmentalists as the “dirtiest” of all fossil fuels.

Over 40 countries – minus two of the three biggest users, the United States and China – committed to shift away from coal power, including Indonesia, Vietnam, Poland, and South Korea, while multinational banks and financial institutions agreed on a time frame to stop funding coal-related businesses.

Coal is the most abundant fossil fuel on Earth, and has been used in heating for millennia. It is relatively inexpensive to excavate or to generate energy. At US$7.5 per thousand British thermal units (Btu) as of October 8, coal costs almost half of oil, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Natural gas, with half the carbon footprint of coal and 25 per cent less than oil, was priced from US$5 to US$15 per thousand Btu in major developed markets.

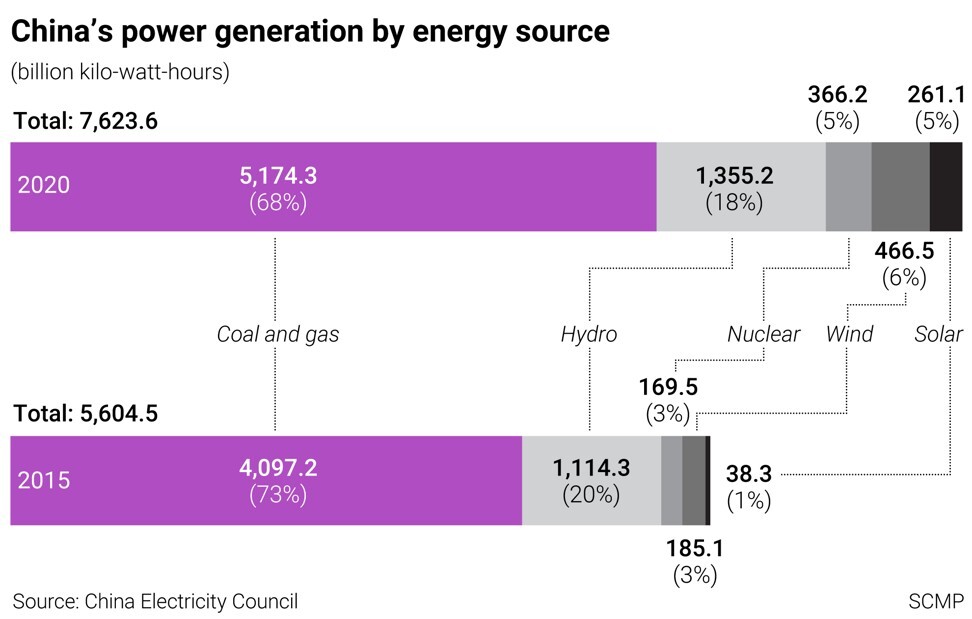

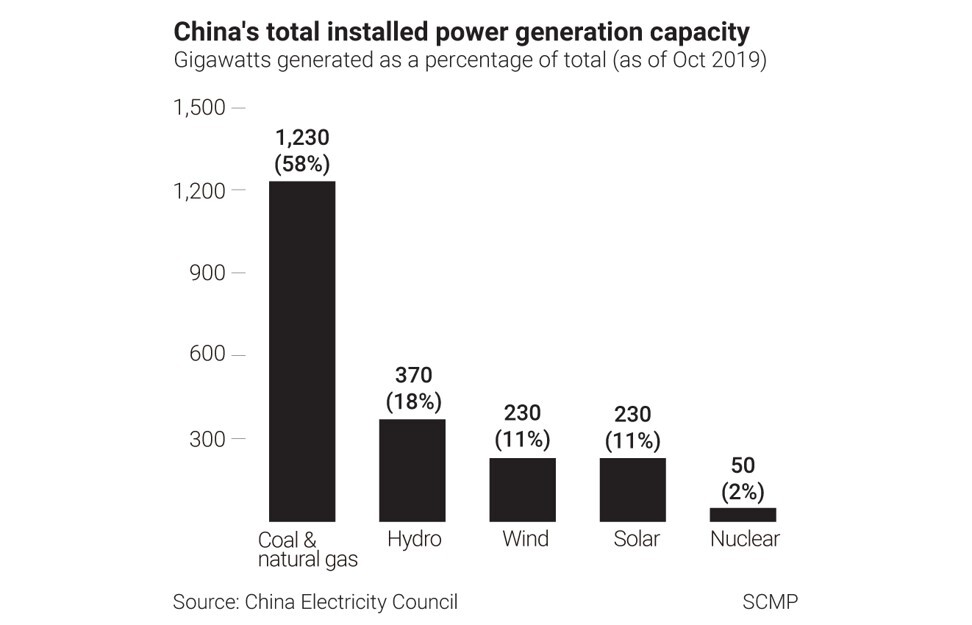

China’s electricity plants, which burn coal for two-thirds of the power they generate, belched out 4.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2019, triple the 2001 level, accounting for 40 per cent of the nation’s total emissions, according to Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research. On top of that, another 3.3 billion tonnes emitted by the industrial sector came from coal-reliant steel and cement industries.

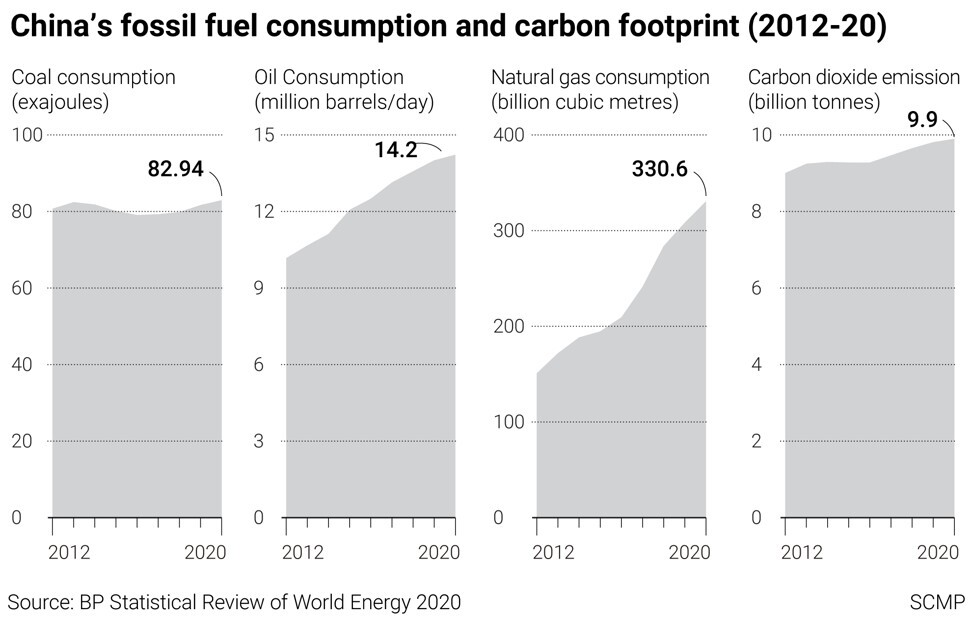

On the flip side, China is the world’s largest consumer and producer of coal, which explains why the nation’s coal policy plays such an outsize role to worldwide efforts to fight climate change. China used 4 billion tonnes of coal in 2020, according to the China National Coal Association.

China had 13.3 per cent of the world’s proven coal reserves at the end of 2020, less than Russia’s 15.1 per cent and the 23.3 per cent hoard in the United States, according to data by BP.

China is largely self-reliant on coal because it is relatively well-endowed with the resource, said Qin Yan, lead carbon analyst at global data provider Refinitiv. Imports contributed just 8 per cent of the demand of both thermal coal for burning, and coking coal for steel production.

“This is in stark contrast to China’s resource endowment of oil and gas,” said Morningstar’s senior equity analyst Jennifer Song, noting that nearly half of China’s natural gas consumption is imported. Oil imports made up 73 per cent of demand last year.

The nation had around 1.5 per cent of global proved oil reserves but accounted for 16.1 per cent of the consumption last year, according to BP. It had 4.5 per cent of the world’s gas reserve, and made up 6.9 per cent of the demand.

“The recent energy crunch has reminded people that coal supply in China too can be restricted by short-term supply-demand mismatch,” Qin said. “At times, there are also regional transport bottlenecks from western production regions to markets in the east.”

The crisis – the result of tighter mining safety rules and a rigid electricity pricing model that bled power producers amid out-of-control coal prices – became an embarrassing distraction and raised questions whether China’s 2025 peak coal consumption target could be met. It forced Beijing to relax mine operation regulations, reform power pricing, pressure miners to cap prices, and order them and coal-fired power generators to boost output to keep the economy humming.

The crisis has actually done China a favour, optimists said, by spurring long-awaited reforms that would help with its long term decarbonisation by making coal power prices more market-oriented.

A new policy mid last month requiring all coal power plants to sell to the wholesale markets will help accelerate the phase-out of coal plants, said climate data provider TransitionZero’s co-founder Matthew Gray.

“This policy will prove to be the final nail in the coffin for new coal plant investments in China – and potentially make it possible for the world to align coal electricity with the 1.5 degree target,” he said.

It’s also a major step in the deregulation of the price of coal power, fully subjecting it to competition from renewable energy. Currently, coal power’s prices and dispatch volumes are mostly state-regulated.

Beijing, well aware of the risk, has recently reiterated its long term determination to achieve a drastic makeover of its energy structure.

According to the latest framework for achieving peak carbon and carbon neutrality released on October 24, the country is aiming to cut its reliance on fossil fuels to below 20 per cent by 2060.

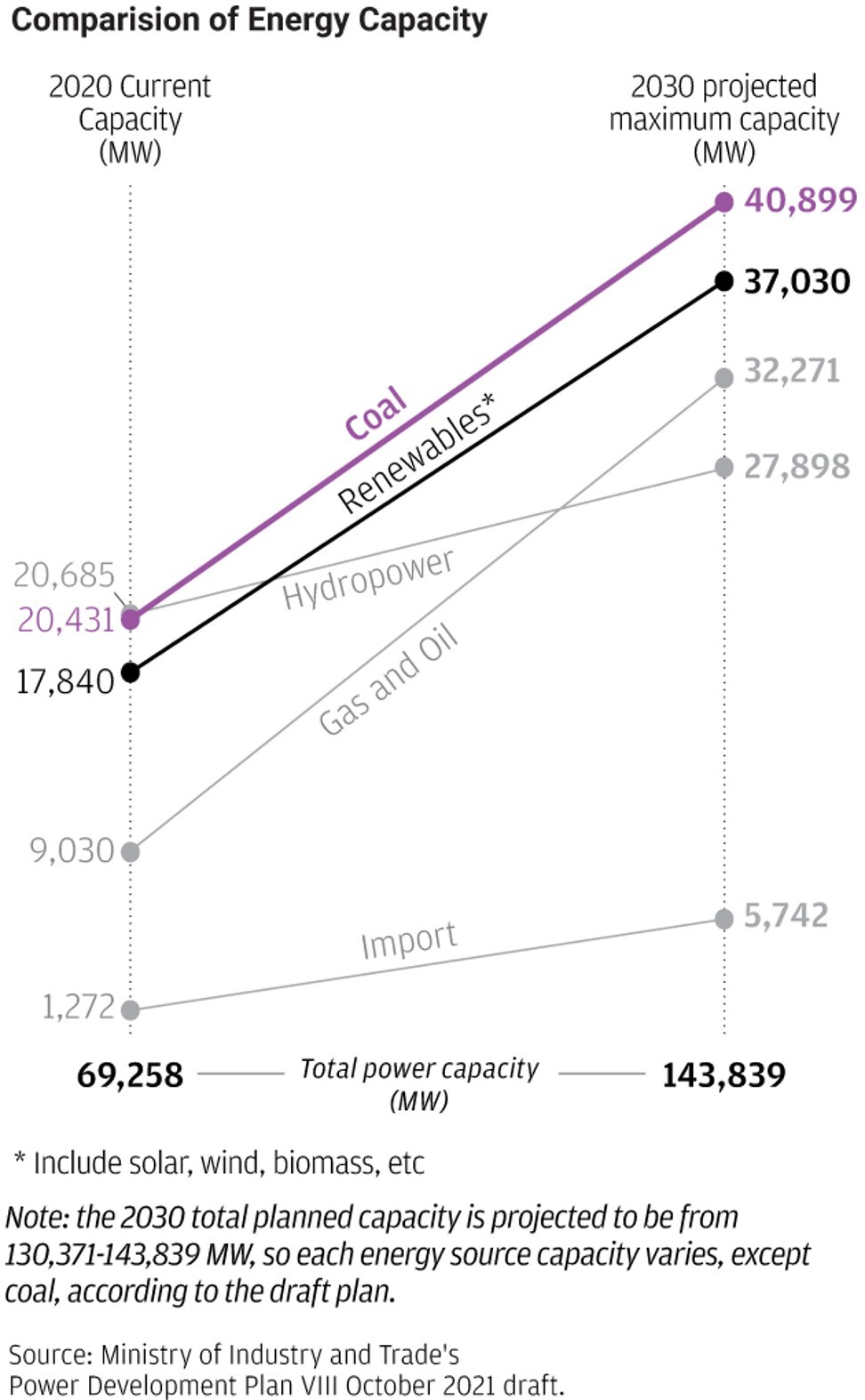

The plan will see China’s installed wind and solar farms reach 1,200 gigawatts in generation capacity by 2030, more than double last year’s level.

China is already a leader in renewable energy production. By the end of 2020, the nation had 281.5GW of wind and 253.4GW of solar power generation capacity, both the largest in the world, according to the National Energy Administration.

Non-fossil fuels accounted for only 16 per cent of China’s energy consumption last year. Renewable energy’s supply intermittency means power companies need to invest much more to overcome technological and cost challenges, to make deployment of energy storage much more widespread to compensate for the shortcoming.

In the meantime, coal-fired power – and near zero-emission nuclear electricity to a smaller extent – will still act as so-called base load supply to ensure power grid stability and energy security.

China’s predominantly state-backed power generators will have to do the heavy lifting in the nation’s energy transition.

According to climate risk data provider TransitionZero, to meet the 1.5 degrees target of the Paris Agreement, the world must shut down 3,000 coal power plants, or one a day from now until 2030. Half of them are in China.

Unlike Europe, where the coal phase-out in the power sector was first coupled with growth in natural gas-fired capacity, before gradually transitioning to renewable energy, China’s time frame for change would be much shorter, said Refinitiv’s Qin.

“Given that imported gas is costly for China’s gas-fired plants, and reliance on gas imports is another concern, China’s power sector transformation will be more like coal to renewables, rather than coal to gas to renewables,” she said.

To be sure, China’s coal industry has done a lot to reduce pollutants, closing old and inefficient power plants, deploying large numbers of sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxide scrubbers, and cranking up the standards for new and more efficient coal plants.

“The efficiency of China’s coal-fired fleet continues to improve, and the average amount of coal used for each kilowatt-hour of electricity sold has dropped more than 20 per cent to less than 310 grams in 2020, from 392 grams in 2000,” said Song.

Another uncertainty for its decarbonisation pathway has to do with its past propensity to lean on heavy industries to stimulate growth when the economy falters.

After the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic subsided last year, China again cranked up industrial and infrastructure construction activities to drive economic recovery.

While heavy industries – especially steel and cement – got a major boost, they played the main role in driving China’s carbon emission up 0.6 per cent last year, in contrast to global decline of 6.3 per cent due to the pandemic.

To reduce emission in the two industries, China needs to transform the energy structure and optimise its economic structure to rely less on carbon-intensive activities, said Li Shuo, a senior global policy adviser for Greenpeace East Asia.

“If you want to reduce coal consumption in the steel and cement industries, there is only one way in the short term, which is to reduce their demand,” he said.

Meanwhile, coal miners are lobbying for a slower phase-out, giving them time to adjust their business strategy and survive in the long term. They are pinning hopes on future commercialisation of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies to extend the lives of coal mines and power plants.

“Coal still plays a critical role in the modernisation of countries and economies,” said Antonios Papaspiropoulos, director of global communication at World Coal Association. “Climate change science and the Paris Agreement are quite clear that … to achieve a net zero emissions future, all fuels and all technologies will be necessary.”