Chun Wo's legal battle involving Li Ka-shing thrusts it into limelight

Small property player Chun Wo Development has been thrust into the limelight over its legal battle with Asia's richest man, Li Ka-shing

Chun Wo Development is a small player that has found itself punching above its weight in a legal battle involving Asia's richest man, Li Ka-shing.

Chun Wo was suing for outstanding payments totalling HK$335 million for work carried out at the almost-completed Tsz Shan Monastery in Tai Po.

Cheung Kong Property Development, a unit of Cheung Kong (Holdings), is the project manager of the two-storey building that drew publicity for its bullet-proof doors and windows.

Li earlier told media that he and his charity had donated HK$1.5 billion to the project. At the time, Li said many important people from around the world would visit the monastery, thus necessitating the extra security.

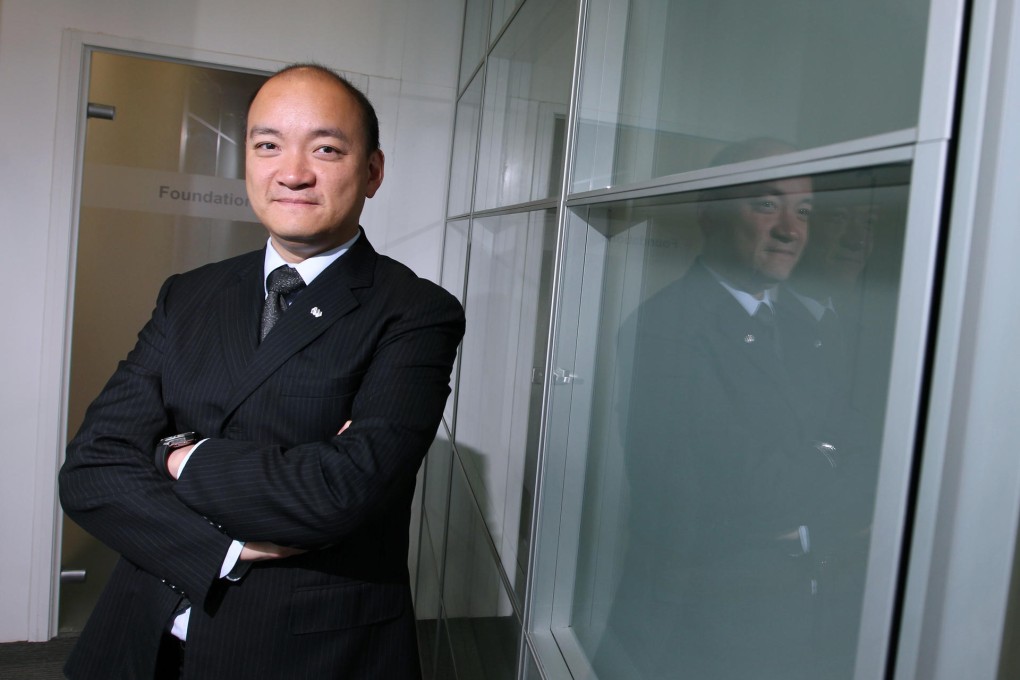

"Bringing the issue to court is something that we really do not want to do," chairman Dominic Pang Yat-ting said, adding that the decision to do so was made only after serious consideration. Pang declined to go into detail, saying legal proceedings had started.