New | Bank of East Asia hopes the worst is behind it, but China’s economy disagrees

Brian Li, the bank’s deputy chief executive, says that technology offers a chance for foreign banks to compete in China in personal banking

In just four years, Bank of East Asia saw its China business went from rosy to bleak.

The downtrend, which the bank was quick to point out, mirrored the overall slowdown in China, where growth slid from 8.6 per cent in 2013 to 6.7 per cent last year.

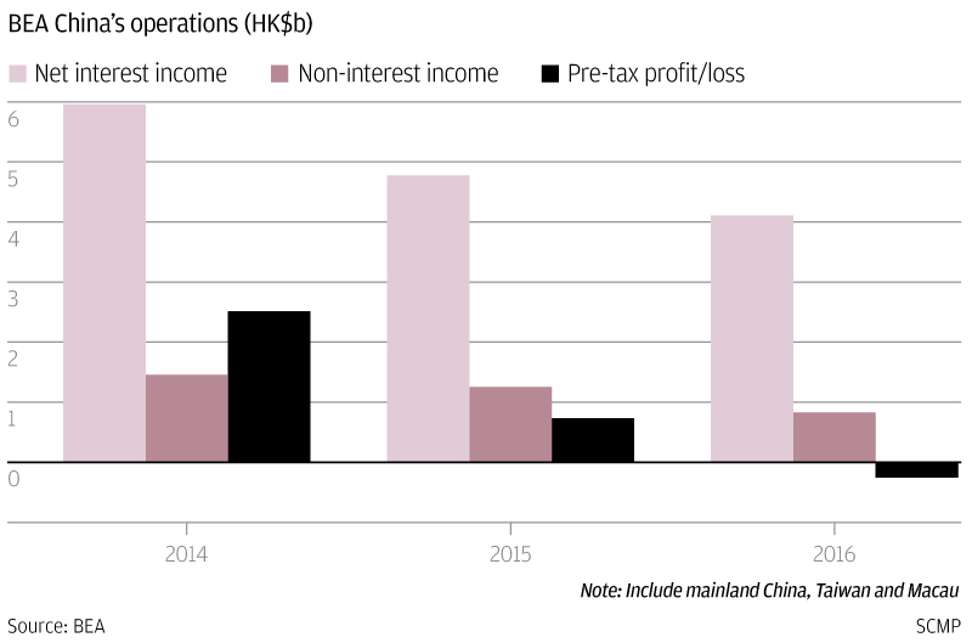

“No doubt last year was a very challenging year, in which we reported a loss for our China operations mainly because of credit costs,” deputy chief executive Brian Li Man-bun said in an interview with the South China Morning Post. “I am very hopeful that this year we will return to profitability.”

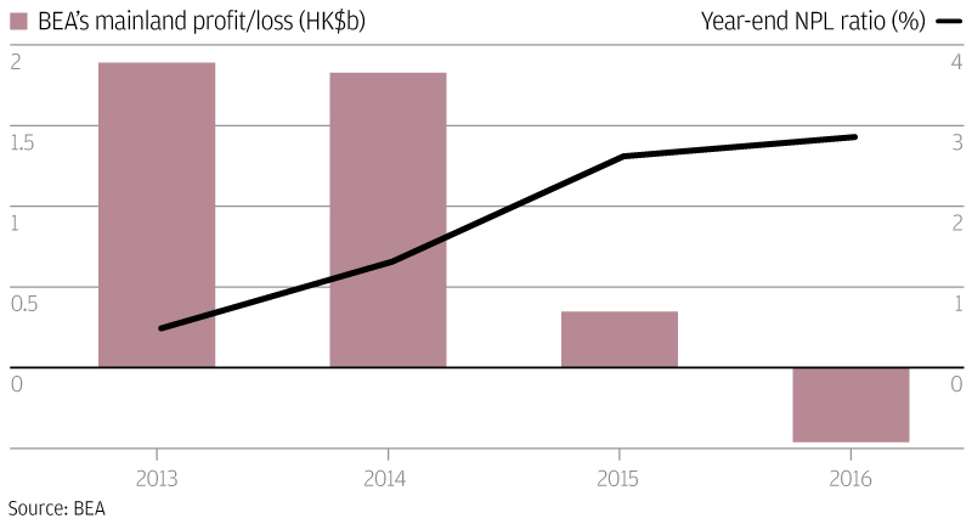

Last year’s performance caps a troubled few years for the bank in mainland China during which its profits have declined steadily to HK$347 million in 2015 before turning into a loss last year.

At the same time, the scale of its non-performing loans also increased, accounting for 0.5 per cent of all the loans in 2013 to 2.6 per cent last year.

“The mainland angle served as a bright spot for Hong Kong banks until the past two years,” said Lim Sue Lin, a banking analyst at DBS Vickers. “Asset quality deterioration was seen in Hong Kong banks’ mainland China exposure, with BEA being the worst hit due to its large exposure” of assets and profit contribution from mainland China.

The bank, established nearly a century ago in Hong Kong by Li’s great-grandfather Li Koon-chun, was looking at reducing its exposure to smaller enterprises and focusing instead on medium and larger players to offer onshore and offshore services. Li’s father David Li Kwok-po has been the bank’s chairman and chief executive since 1997 while elder brother Adrian Li Man-kiu has served as deputy chief executive since 2009.

Brian Li rejected the suggestion that the latest cuts showed the pace of growth had been too fast.

“I would not say we have over-expanded. What we have is still very worthwhile. It is just the case that the operating environment has changed,” he said.

Following the regulatory changes in 2007, BEA, through wholly owned subsidiary BEA China, was able to expand its banking services to individual Chinese consumers.

As it could not compete by size and scale with the Chinese banks, Li said BEA was “a niche player” targeting the more affluent customers in large cities, particularly those intending to invest overseas, and cross-selling personal banking to corporate clients and their employees.

Like its foreign peers, BEA has a marginal share of the domestic personal banking market, but Li is optimistic that technology can change that.

“That is why we are looking to partner with a number of Chinese technology companies,” he said, though he declined to elaborate on the format of co-operation, while brushing aside concerns about competition.

“The market is so big that we will not be the only ones doing this,” he added.

BEA, which will mark its centenary next year, opened its first China branch in Shanghai in 1920.

“We have been operating in China ever since, through the wars and revolutions,” Li said.