Need a new nose? A Nasdaq-listed firm can 3D print one for you

Nasdaq-listed Cellink believes that cosmetic functions aside, 3D bio printing helps drug development for cancer treatment

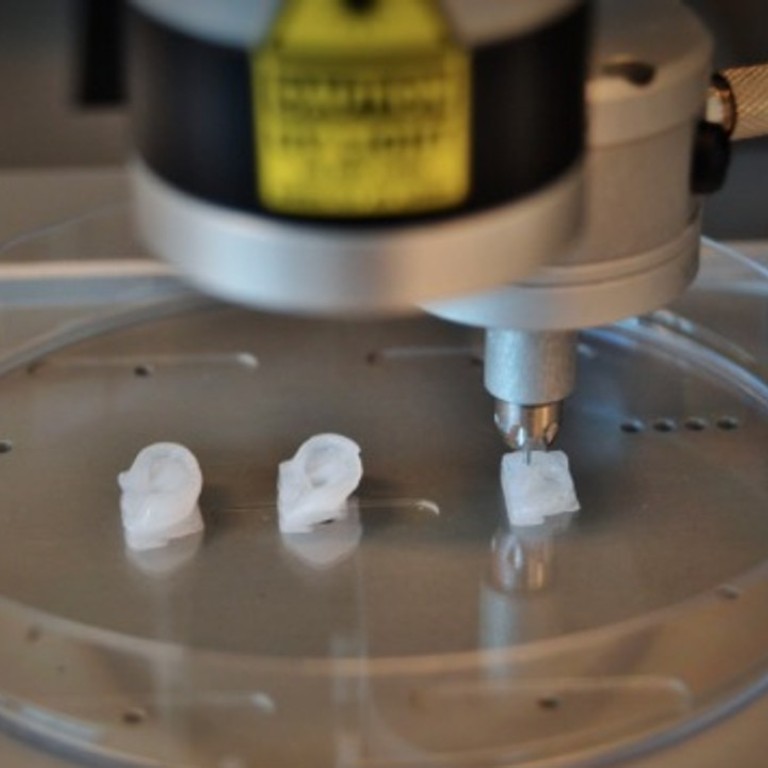

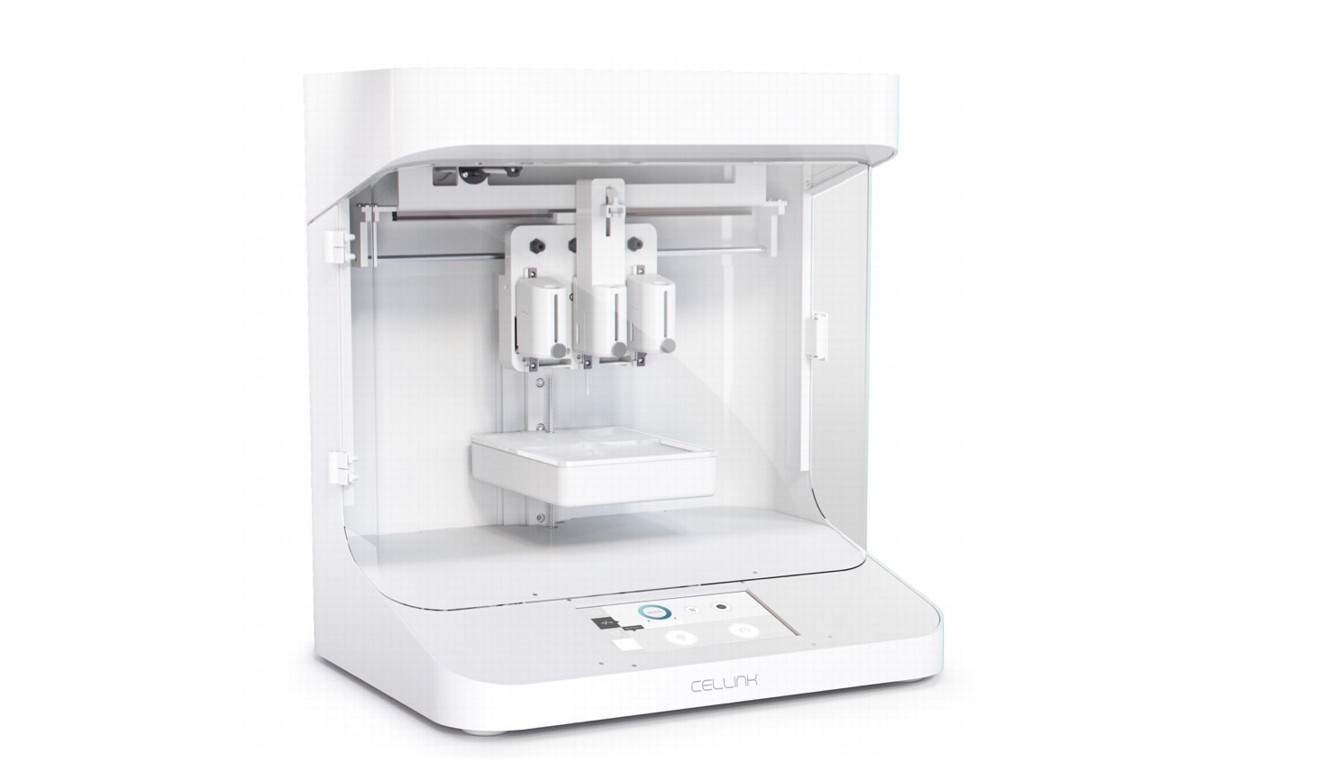

Transplanting is not the only way to get a new nose, ear, cartilage or bone. Biomaterials churned out with “bio-ink” and a coffee machine-sized 3D bioprinter are the new alternative, and this is not Twilight Zone.

Cellink, a Swedish company, with a nimble team of 20 people, are making the rounds pedalling the printers around the world, particularly in China. Founded in January last year, it raised investor eyebrows by going public on the Nasdaq within 10 months, with its shares 1070 per cent oversubscribed.

“3D bio-printing makes it possible for you to engineer cells to grow into a heart valve to replace one that is damaged from heart disease,” Gusten Danielsson, chief financial officer with Sweden-based Cellink told the South China Morning Post in an interview.

“We have seen more companies start adopting it in [cosmetics testing],”said Danielsson, who had just finished a marketing tour around Asia. ”Reactions from Chinese clients truly exceeded our expectations,” he added.

3D bio-printing makes it possible for you to engineer cells to grow into a heart valve to replace one that is damaged from heart disease

While universities and research institutes remain the biggest customer group of these machines, consumer giants such as Procter & Gamble and L’Oreal have attempted to explore 3D printing of things like human skin since 2015 as they try to step away from animal testing.

Realising that “few researchers in the field wanted to build an industry,” Cellink’s founders attempted to build their first prototype 3D printer, with an affordable price tag of US$10,000 in 2015.

But what excites Danielsson more is how 3D-printing can potentially help drug development for cancer treatment, as it allows scientists to print the same cancer tumour numerous times to test a broad range of medications and compare their effectivenesses.

Traditionally, new cancer medications are first tested on animals, but critics have long raised concerns that what is effective in monkeys, for instance, does not necessarily have the same impact on humans.

“With advanced materials and different temperatures, we can print bones, liver tissues, factures, noses and skins,”Danielsson said.

Facing an acute shortage of organ donations, scientists have also tried to bank on 3D printing in their race to build biosynthetic organs.