Dirty fighting in some of Hong Kong’s wealthiest families may undo value of kinship

Family-owned businesses, when they are well-managed and cohesive, can outperform other types of corporate structure, according to a 2015 Credit Suisse report, which studied 920 family-controlled enterprises with at least US$1 billion in market value.

Their average annual revenue grew 10 per cent from 1995 to 2015, better than the 7.3 per cent increase among members of the MSCI Index in the same period.

“Family businesses appear to demonstrate superior cash returns and economic value creation, underpinning premium valuations and share price performance,” the bank said.

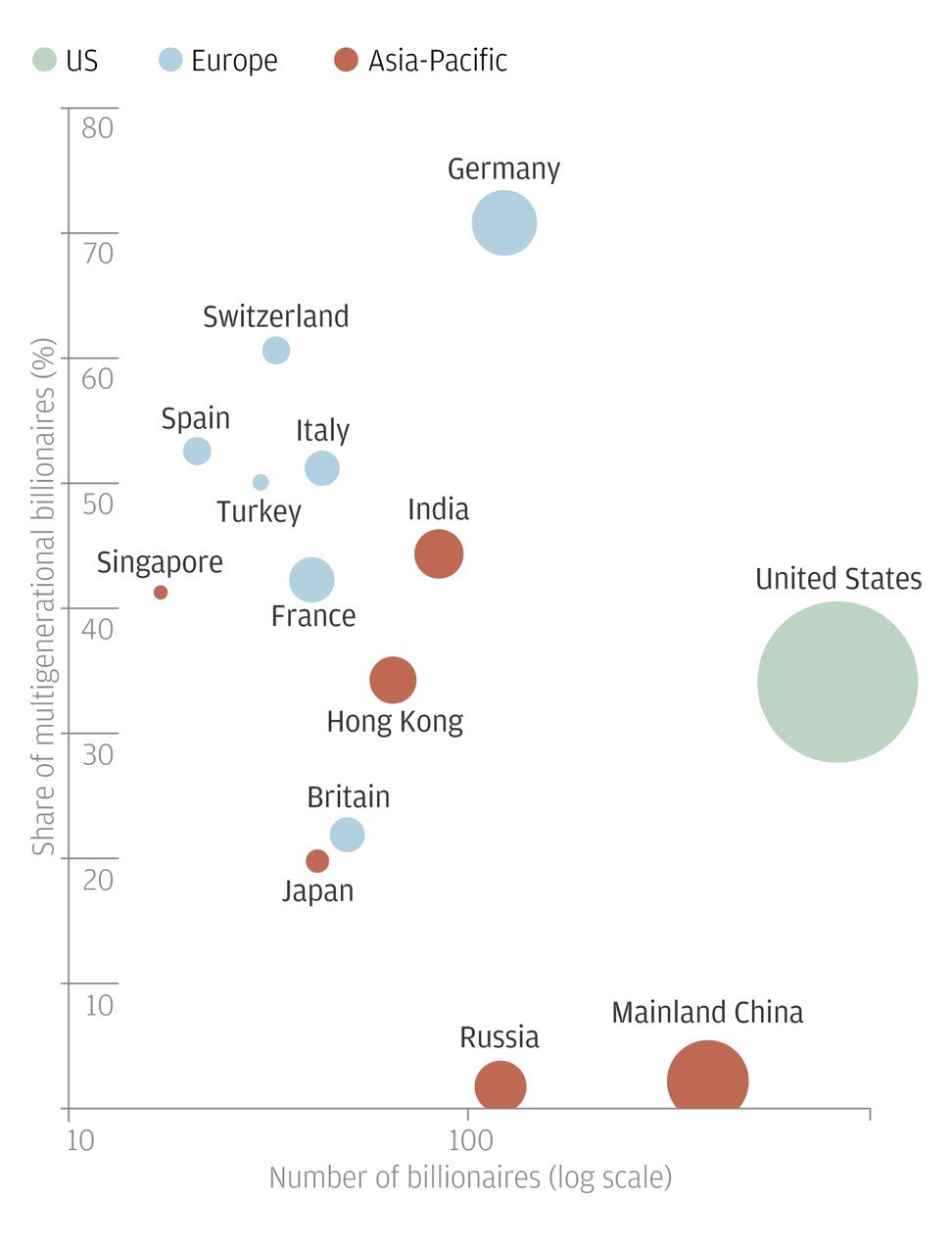

Hong Kong had the fifth-largest representation in Credit Suisse’s study, after the United States, mainland China, India and Switzerland.

The family business would “remain prevalent and effective” in China for the next 30 years, said Joseph Fan, a Chinese University of Hong Kong professor who specialises in family businesses.

“The problem with the Chinese family is that wealth doesn’t transfer until upon death or upon the passing away of the patriarch,” he said.

When they disintegrate into feuds, family businesses and business successions in the top echelons of Hong Kong society can be the fodder of soap operas and tabloids.

In publicly traded companies, these feuds have the potential of straying into corporate boardrooms and move markets, where billions of dollars are at stake for minority investors.

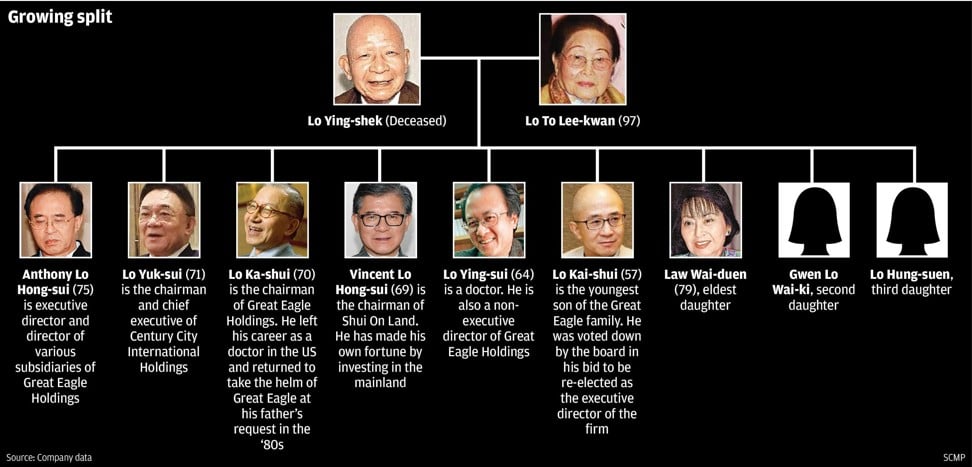

The Lo family, one of Hong Kong’s wealthiest real estate developers, has not been spared the feud among its second-generation members.

Founded by the late Lo Ying-shek (羅鷹石) and his wife in the ’60s, Great Eagle Holdings controls two public companies valued at more than HK$60 billion (US$7.7 billion). The patriarch, who passed away in 2006, appointed his third son Lo Ka-shui (羅嘉瑞) as the group’s chairman and established a family trust overseen by HSBC International Trustee.

The family, comprising six sons and three daughters, has been divided into two opposing groups: the eldest, second and youngest sons support their mother in dismissing HSBC while Great Eagle’s chairman Lo Ka-shui is aligned with his fourth and fifth brothers in opposing the move.

The split came to a head on Mother’s Day this year, when the three sons supporting HSBC’s dismissal joined their mother at a banquet while the others were prohibited from joining, according to Vincent Lo Hong-sui (羅康瑞).

“Trust between the two parties is completely lost,” said Vincent Lo, the fourth son of the family and chairman of Shui On Land, who is aligned with his elder and younger brothers in opposing HSBC’s dismissal. “At this point, I don’t know how we can reconcile this situation.”

On her part, Lo To Lee-kwan was opposed to the public airing of the family’s feud, the matriarch said through a spokesman, refuting claims that she had been manipulated.

“I feel a little bit sorry for HSBC,” said John Ashwood, Hong Kong managing director at Zedra, a trust services specialist. “What’s going on has nothing to do with the working of the trust but rather a dispute within the Lo family.”

“The problem with a trust is that when they disagree with each other, they cannot directly buy each other out because they are not the true owners of the family assets,” Fan said. “The assets belong to the family trust. They are only the beneficiaries.”

He said internal reconciliation was impossible in this scenario because the family trust was a legal structure, which was very hard to change.

“A proper way of succession planning is to prepare the people before the wealth transfers,” Fan said. “It takes a long time, say 20 years, to prepare family members to learn to collaborate and share love and relationships.”

Other wealthy Hong Kong families had also previously engaged in all-out feuds. The most notable cases involved the family of Sun Hung Kai Properties in 2008 and the family of Nan Fung Group in 2012.

In 2008, SHKP chairman Walter Kwok Ping-sheung, who had led the company for 18 years after succeeding his late father, was ousted by his siblings and octogenarian mother following his relationship with a female “confidante”, which was disapproved by the family. His position was not restored until 2014.

In 2012, after Chen Din-hwa, founder of Nan Fung, passed away, his former wife sued her youngest daughter, Vivien Chen, in a dispute over the distribution of assets. The mother, who had divorced Chen, won the lawsuit and was bound to receive a one-third entitlement, which was worth considerably more than HK$1.5 billion.

The family clan of casino tycoon Stanley Ho Hung-sun, comprising 16 children and four wives, has not been free of disputes either. The gaming mogul, now 95, filed a lawsuit against some of his family members in 2011 in a dispute over a stake in his Macau casino empire valued at about US$1.6 billion.

He dropped the lawsuit after his family members came to a mutual agreement on the stake, but not before airing much of the feuding in public.

“Wills, trusts and estate planning are necessary succession planning activities, but they may not be sufficient to avoid disharmony during generational transition, particularly where large sums of money or assets are at stake,” said Thomas Ang, head of family office services for Asia-Pacific at Credit Suisse.

The article has been amended to say Lo Ying-shek passed away in 2006, not 2009, in the 11th paragraph