Four decades of Chinese capitalism show how trade and investments benefit everybody

Foreign enterprises added US$3 trillion to China’s economy since the country opened up to trade and investments, and helped create 210 million jobs, based on Mike Enright’s calculation. Donald Trump should take note, as should India, Indonesia and Vietnam.

Back in the early 1980s, China’s government-owned news agency, Xinhua, organised small exploratory tours into the Pearl River Delta for foreign journalists as the country began the process of opening its doors to the outside world. I joined many of them, and greatly regret that they abandoned the practice soon after.

The overriding memory, as we bumped along muddy roads past quaint and scruffy villages clustered around murky duck ponds and wallowing water buffalo – prettier to photograph than to live in, no doubt – was mile after mile of rice paddy and towering sugar cane fields.

In particular, I remember stopping off to explore a new bus-making venture. Under a high shed roof stood two wheel-less buses sitting on wooden blocks with workers hand-hammering panels of sheet metal. We were told by an apparently proud overseer that they could make six buses a year.

Over a period of 35 years, the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) has grown 28-fold. Last year, China made over 24 million cars and 3.7 million commercial vehicles – about one third of total world production, and around six times the size of the US industry.

The story of this growth is a story of foreign investment, and a recent fascinating study by Mike Enright at Hong Kong University and funded by the Hinrich Foundation has tracked that change, and brought some rigorous and hard numbers to the role that foreign investment has played in that transformation.

We all know the role has been big. What we did not recognise is how big.

Based on nominal foreign investment flows that have risen from an average of a couple of billion dollars a year in the early 1980s to more than US$110 billion a year over the past decade, accumulating to a total of around US$1.6 trillion, Enright calculates that foreign industrial enterprises by 2013 accounted for 33 per cent of China’s GDP, and 27 per cent of employment.

That means a US$3 trillion contribution to GDP, and over 210 million jobs. In an area like computing it is more than double that.

And yet, proud nationalist voices are beginning to arise in China that claim the country’s emergence to be the world’s second-largest economy could have happened without inputs from these tens of thousands of foreign invested enterprises, and that even today they make a limited positive contribution to the economy. Enright’s robust response is that this idea is nonsense.

If you rely on nominal data, it’s easy to think the Chinese may have a case. Foreign invested enterprises account for just 2.5 per cent of gross capital formation, and 0.5 per cent of China’s fixed assets. The economy relies increasingly today on consumer demand within its own economy, rather than on the export-led model so publicised through the 1980s and 90s. But bring together the economic impact data, and the cascading benefits arising from foreign investors over the past three decades, and the story is definitively different.

In the process, China not only lifted itself away from abject poverty, but also provided a template worthy of careful study by other massive developing economies like India, Indonesia, and perhaps even Vietnam.

At a time when Hong Kong is trapped in a self-doubting funk over its present and future competitiveness, Enright provides an important reminder of how, even today, China’s progress relies heavily on Hong Kong.

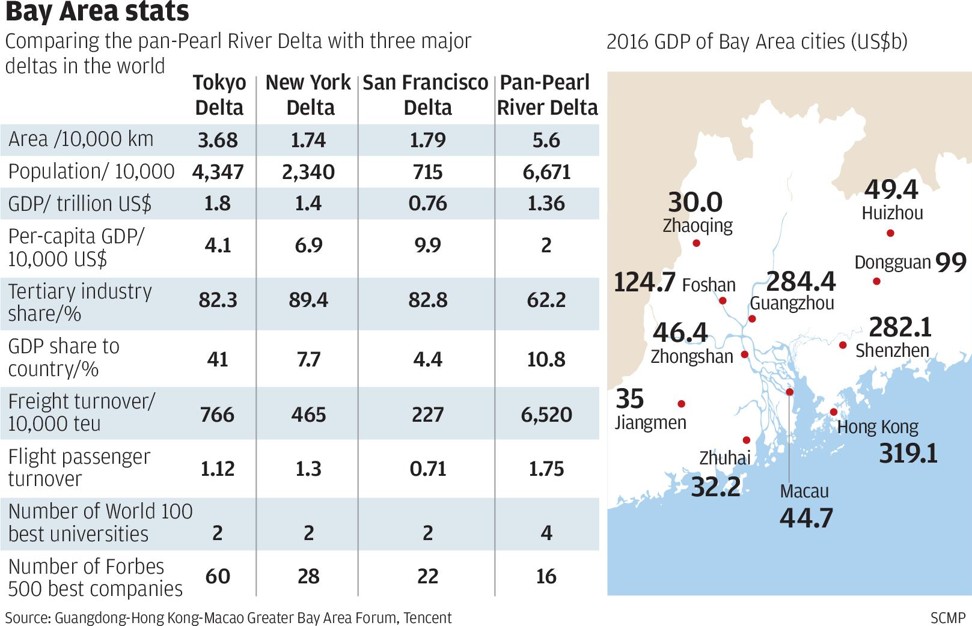

Over 47 per cent of all investments in China had over the past 35 years been by Hong Kong investors, or were channelled through Hong Kong. While this investment has been spread across the entire country, Shenzhen’s growth from a fishing village of 30,000 to a high-tech metropolis of more than 10 million people is significantly due to Hong Kong investment.

While I can see the Enright work digested and acknowledged by Beijing’s economic planners, I have a passing worry. If I were sitting today in the Trump White House, I would look at the compelling evidence of the Enright study, and say: “I told you so! The trade and investment of the past decades had been America’s gift to the developing world. China’s gain. Our loss. It has hugely helped them to grow, but this has been at our expense.”

Before he lets Steve Bannon or Peter Navarro scamper off along that line of erroneous thinking, Donald Trump should first talk to those US companies like P&G that have invested heavily in China. While P&G exports some of its China-made products – some no doubt back to the US – the vast majority of its US$11 billion sales are to domestic Chinese consumers. Building into the Chinese economy has enabled strong US companies like P&G to remain global leaders, at no expense to US workers, and to the considerable benefit of US consumers.

Enright’s advice to China sceptics on the value of free and open trade and investment has equal resonance to Trump’s sceptical White House: “Even if Chinese companies and indigenous investment could provide everything that foreign companies and foreign capital can provide today, it would still make sense for China to be open,” he wrote. “No single economy, no matter how large, can generate all the ideas needed… No single economy can produce companies that are world leaders in all industries.”

Trump may believe deeply in “America first”, but if he wants it to stay first, it will be on the back of free and open trade and investment.

China’s experience tells you why. India take note. Indonesia take note.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view.