Economics lessons to be learned from Mugabe

Former President Robert Mugabe’s economic mismanagement cost the country dearly; inflation rocketed to 231,000,000 per cent in 2008

I only met former President Robert Mugabe once. It was in Hong Kong with a small group of investors. The diminutive dictator walked up to the podium past a huge bemedalled man in full military dress, standing enveloped by an even huger pot plant.

The general left the pot plant for a moment to place Mugabe’s speech on the podium. The little tyrant took one look at it, rolled his eyes, turned the speech the right way up and commenced. He was just as effective in reversing the prospects of Zimbabwe’s economy.

Mugabe’s sole and selfish aim in being president was … to remain president. By paying off his supporters, and using the knobkerrie and the gun on everyone else, he lasted 37 years. He was a great advertisement for colonialism, which had at least some concern for the people under its administration.

God blessed Rhodesia with the world’s best climate and vast mineral resources. Rhodesia in the 1960s boasted huge earnings from arable crops, tobacco, and mining. A democratic leadership could have made it highly successful – the Switzerland of Africa.

When I left Zimbabwe in 1969, it was the breadbasket of Africa, now it is now a basket case, spending precious foreign currency to import food. The black population was poor but safe and not subject to overt racism. The churches ran the schools and despite the fact that much of the education budget does not reach the schools today, Zimbabwe has a literacy rate of 90 per cent. The people are lovely, kind and generous – or Mugabe would not have survived.

Mugabe’s prioritisation of power over economics caused millions of early deaths through starvation, disease, and murder – including that of my friend and brave journalist, Mark Chavunduka. Fear and poverty hinder economic productivity. Life expectancy in Zimbabwe is 60 years (down from 64 in 1990), 74 per cent of the population live on less than HK$45 (US$5.76) a day (lower than in 1980), and just 10 per cent of the population draws a salary. Zimbabwe’s economy at US$16 billion is only the same size as HSBC’s latest quarterly revenues.

Mugabe’s key economic mistake was to destroy the means of production through racially inspired genocide. Land was brutally “redistributed” by driving white farmers off the businesses that their grandfathers and great-grandfathers had hewn out of the bush. The swag went to favoured cronies who were too busy rifling the public purse to manage the land. Flying into Harare reveals the devastation caused by greed and neglect, with fallow farmland littered with crumbling irrigation ditches, rusty equipment, and miles of decaying wooden frames built to dry tobacco.

As things got worse, Mugabe printed money to pay his bills. Inflation rocketed to 231,000,000 per cent in 2008. I bought a $100 trillion Zimbabwe dollar note in 2010 for 40 HK cents. By then, the US dollar had replaced the currency and saved the economy.

I cannot help feeling that the only difference between Zimbabwe and ourselves is blind confidence, for in the last 10 years European, Japanese, and US central banks have also printed money to stop the world falling into recession. We do see the resulting inflation though; in real assets like property.

Despite his incompetencies being widely exposed, Mugabe was lauded as a revolutionary hero – but he was really a bit player. He was jailed for soliciting violence, but like Macbeth, he knew that the true enemy was his senior revolutionary colleagues – he got rid of them to become leader. Other African leaders, afraid of their own legitimacy, found it difficult to criticise him.

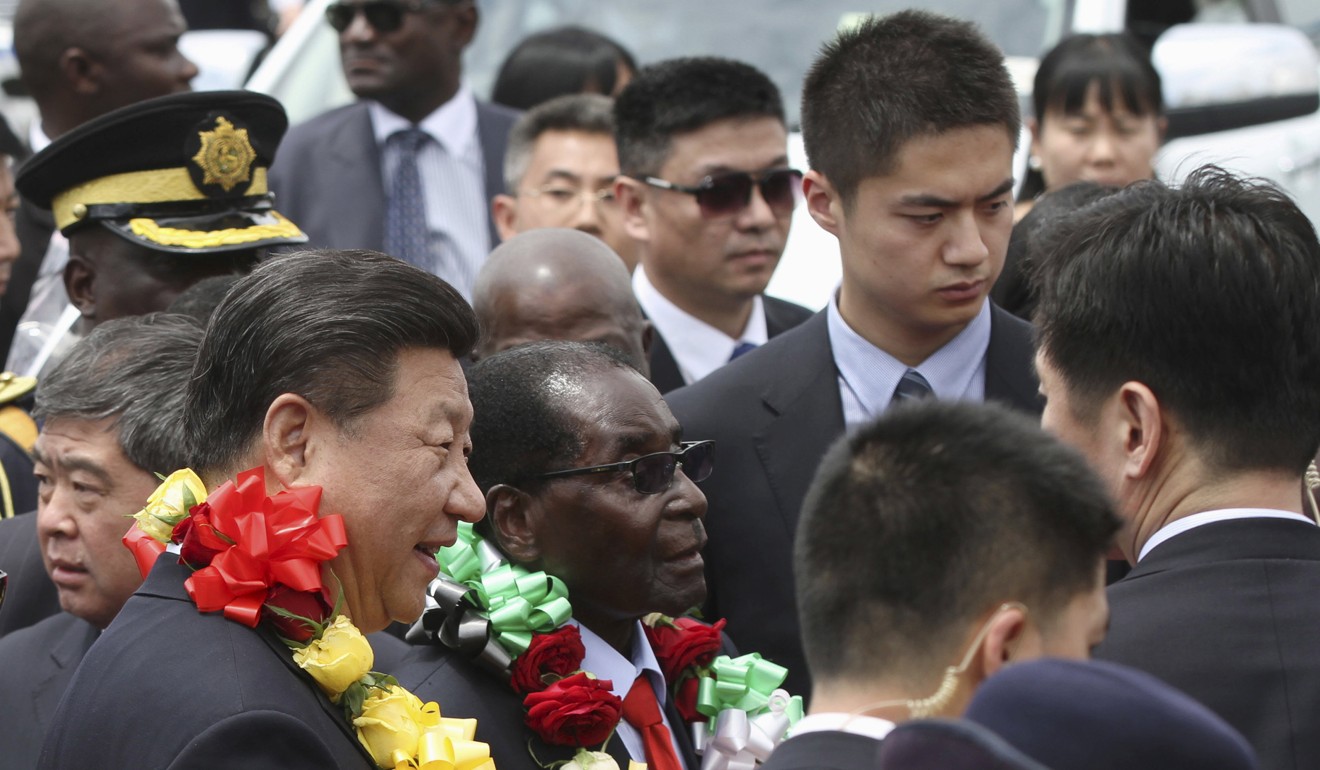

He remained a dilemma for China, with its policy of non-interference, but they still heavily backed investment into the country. In 2015, President Xi Jinping himself visited Harare and separately Mugabe was awarded the Chinese Confucius Prize. This largesse was not to last. The general who launched the non-coup against Mugabe was told in Beijing last month that investment would stop unless the leadership put the economy before politics.

It begs the question as to how China’s Belt and Road Initiative will cope with other mismanaging leaders. Do you back the man in charge who may turn out to be the wrong horse (as America did with Batista in Cuba or Diem in Vietnam), or do you work with more people-friendly leadership?

Sadly for Zimbabwe, Mugabe is unlikely to be replaced with an accountable leader, more likely another dictatorial clone. Our thoughts should be with the kind and gentle Mashona and Matabele people. They deserve better.

Richard Harris is an investment manager, banker, writer and broadcaster – and financial expert witness