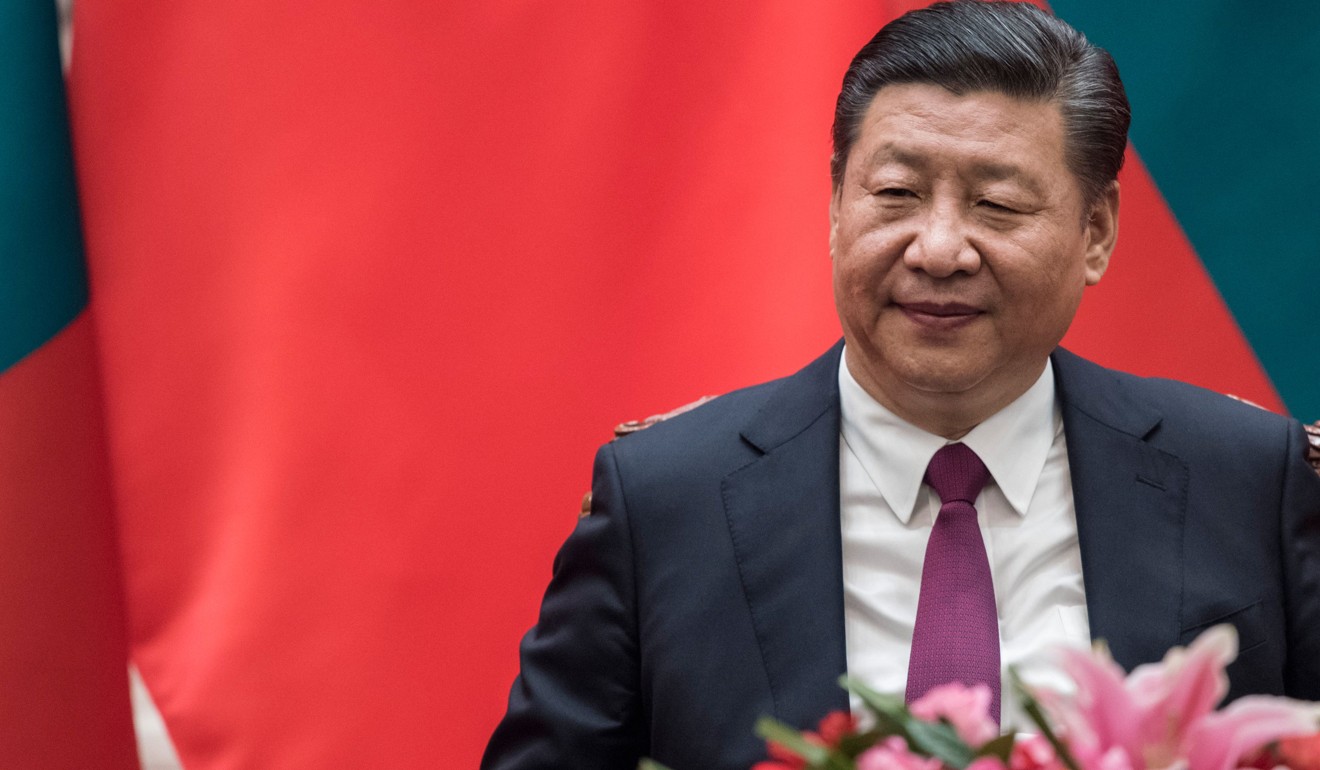

Xi Jinping’s war on shadow banking spills over, rocking China’s wider financial world

Companies that had committed to buying overseas assets are now finding it hard to complete the deals amid China’s financial clean-up of its shadow banking activities and banks’ reluctance to extend loans

Beijing’s tightening rein on shadow banking activities, under President Xi Jinping’s call to tame risks, is opening a can of worms in the country’s wider financial realm as deals are falling apart and debts remain unserviced.

As banks refuse to roll over debts, shadow lending channels blocked and the value of pledged shares of listed companies shrinking, deals that were once regarded as good are quickly turning sour.

James He, a senior executive with a Beijing-based manufacturing and health conglomerate, is one of those caught off guard by the change.

He, who declined to name his company for fear of causing a sell-off in related shares, told the South China Morning Post that his firm had decided to invest abroad when money was easily available and its share price was high.

It borrowed money at home and paid US$30 million as deposit for taking over a mid-sized Hollywood film studio in early 2017 – at a time when it was trendy for Chinese enterprises to buy trophy assets such as landmark buildings, sports clubs and studios.

Dalian Wanda, Anbang Insurance Group and HNA Group were grabbing headlines on a near daily basis with their acquisition plans.

But as capital outflows gathered pace amid faster depreciation of the yuan, in June 2017 Beijing stepped in and introduced tighter scrutiny and restrictions to block Chinese companies from buying such assets.

As a result, He’s company was unable to remit funds and make a payment last June as promised.

The studio’s owner, however, said that the deposit will be returned if He’s firm can find a new buyer.

“But it’s almost impossible to find a buyer who has the money ready offshore” and Beijing’s ban on overseas entertainment investment has made the assets even less desirable, He said.

The imminent loss of the US$30 million is only part of the company’s troubles. Back home, the company had used its own shares as collateral to borrow millions of yuan. Now, creditors of the first batch of 600 million yuan worth of overdue loans are knocking on the door while the share price has lost more than 40 per cent of it value from its peak in late 2016.

“We were aggressive in our investment, but the businesses we acquired in China in the last few years did not generate ideal cash flow, while our stock-backed debts met margin calls as market tumbled,” said He. “The cash chain is literally broken and we might lose everything.”

To make matters worse, the doors for emergency relief in times of cash crunch, such as trust or entrust loans, with high interest, are closed. “Since banks are adhering to compliance and risk control they are no longer extending bridge loans to us,” said He. “Besides off-balance-sheet lending, like raising funds through issuance of asset management products or trust products, is no longer possible after the regulatory tightening.”

The situation of He’s company is not unique.

China’s Nasdaq-style index ChiNext slumped by 10.7 per cent in 2017, as investors went underweight on mid and small caps for blue chips, since the former face bigger uncertainties as China’s financial clean-up pushes lending costs higher.

According to financial data provider Wind, in 2018 more than 3,440 A-share companies will face 1.8 trillion yuan (US$285 billion) worth of stock pledged loans mature – they have to be either refinanced or redeemed.

Meanwhile, 145 A-share firms had their shares suspended from trading during the first week of February and 40 of these saw share prices plunge by the daily limit of 10 per cent at leastonce, the Securities Journal reported on Thursday.

In another case, Michael Li, a Hong Kong-based investment banker, is anxiously seeking a buyer for his Chinese client to take over a controlling stake in a US-based entertainment company.

Li’s client, a mainland based property developer, which controls three listed firms, has seen its stake in an A-share firm completely frozen by a court in Wuhan, after missing loan and interest payments worth 213.5 million yuan.

The company had paid about US$430 million for a major stake in the US firm last year, and is willing to sell the asset at a 60 per cent discount.

“They are desperate for cash and even if they sell it at the discounted price it will not be enough to repay the loan,” Li said.

“But few people have cash now and potential buyers from the mainland will also need borrow to take over the stake, which is not easy for now.”

Such stories areclearly early signs of debt stress, which could be in the trillions. According to the People’s Bank of China, financial institutions had 102 trillion yuan worth of assets under management at the end of 2016, and even if a small percentage of these assets turn sour, it could result in something that concerns Beijing the most – systemic risks.

According to the People’s Bank of China, financial institutions had 102 trillion yuan worth of assets under management at the end of 2016, and even if a small percentage of these assets turn sour, it could result in something that concerns Beijing the most – systemic risks

Analysts at Standard & Poor’s Global Ratings said in a research report on January 29 that they believe rising profits alone will not be enough to rescue China’s risky companies as liquidity tightens.

“Last year, profits were boosted by economic reflation, strong commodity prices, and buoyant refinancing conditions … but some corporate borrowers may run aground in 2018 despite continued improving operating conditions.

“Higher yields and spreads in China’s domestic bond market are signalling tougher refinancing conditions for the riskiest borrowers.”

The clean-up of the financial industry intensified after Xi consolidated power at a the 19th party congress last October.

Xi and other top leaders said they would take a three-year approach to winning “critical battles” against financial risk, pollution and poverty, as China strives to sustain quality growth, shifting from growth in gross domestic product numbers.

Liu He, the closest economic adviser to president Xi, and a member of the Communist Party Politburo, stressed on financial risk control in his speech at the World Economic Forum in Switzerland in January.

“In about three years, we will strive to bring the overall leverage ratio under effective control, make the financial system more adaptable and better serve the real economy, prevent systemic risks and facilitate better flow of economic activities,” he said.

Specifically, China’s banking regulator had led a nationwide campaign to crack down on excessive leverage, off-balance sheet banking activities, and interbank borrowing. By the end of 2017, the regulator said it had uncovered 59,700 instances of wrongdoings involving 17.7 trillion yuan.

A record 2.9 billion yuan in fines were imposed last year on 1,877 banks. In addition, 1,547 industry employees were punished of which 270 were slapped with bans from the industry ranging from a few years up to a lifetime.