An arbitration case ‘win’ can be just part of a long legal journey when it comes to Belt and Road

Winning an arbitration is a major milestone in the dispute resolution process for a company, but enforcing the award – especially against a state entity in the host nations covered by the Belt and Road Initiative – is often where the bigger challenge lies.

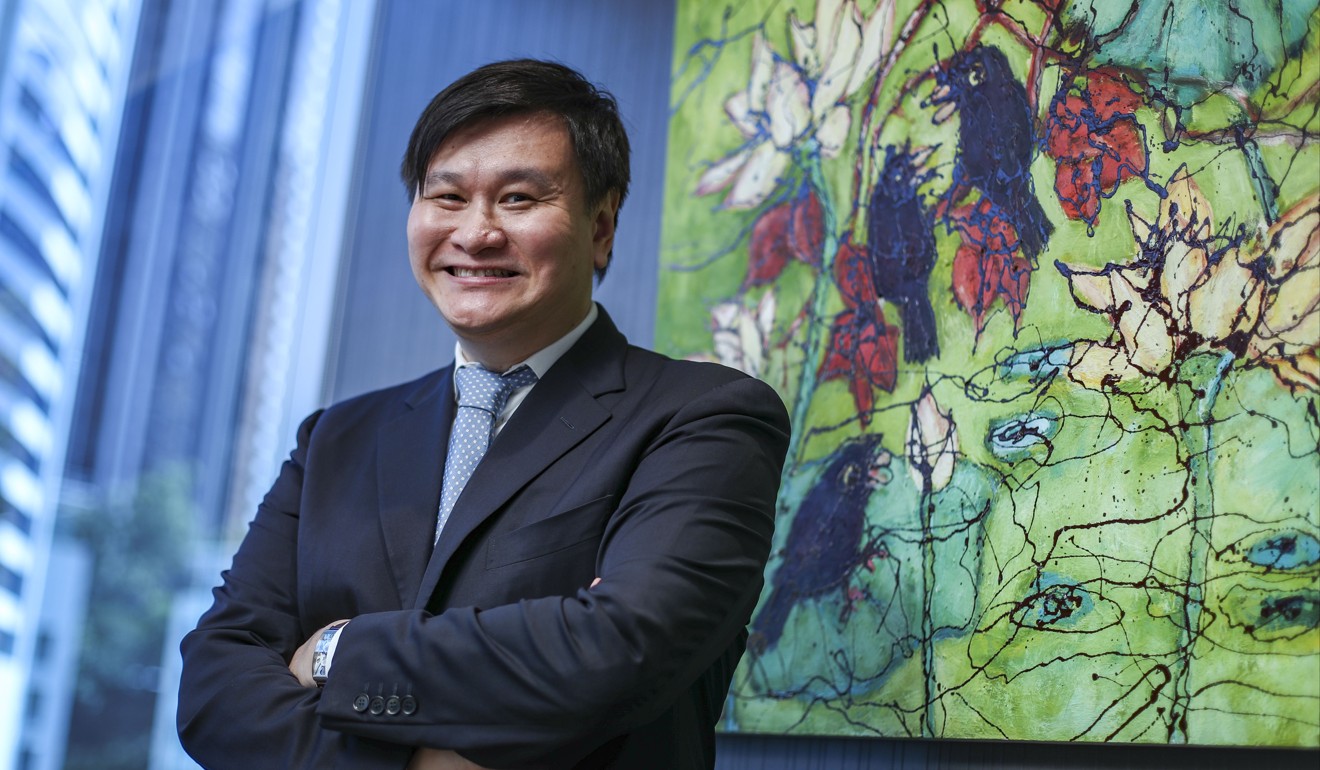

“Enforcement varies from state to state, but in general it has improved in Asia,” said James Kwan, a Hong Kong-based international arbitration partner at international law firm Hogan Lovells. “Judges are getting more sophisticated with training and through collaboration.”

Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, South Korea, and Japan are considered to be “generally pro-enforcement”, while the Philippines, India and Indonesia rank lower down but much improved, he added.

“China has really improved in the last 10 years – public policy hasn’t been used as ground for refusal of enforcement – except in three cases,” he said.

A good track record of enforcing Hong Kong arbitral awards on the mainland has made Hong Kong an attractive place for resolving disputes involving nations covered by the initiative, he said, noting since 2009, only two Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre awards have been refused enforcement on the mainland.

In one case, it was ruled that the disputed issue should have been referred to the Chinese court rather than an arbitral tribunal, while in the other, the award was deemed to have contained “decisions on matters beyond the scope of the submission to arbitration”.

But in Thailand, arguments of contravention of public policy using domestic law as grounds have still been often used by local courts to refuse enforcement of international arbitration awards against a Thai government entity, he noted. The track record of enforcing an arbitration award against non-Thai state entities is better, he added.

In Delhi, the India Act of Arbitration in 2015 should mean enforcement of arbitral awards will improve in the future, he said.

A case in point was observed last year in the enforcement of an award by the London Court of International Arbitration.

The High Court of Delhi ruled in 2017 that the US$1.18 billion award to Japan’s telecommunications giant NTT Docomo against India’s Tata Teleservices was enforceable.

The Court found that a third party, the Reserve Bank of India, had no standing to challenge the enforcement of award, and that the arbitral tribunal has correctly found that Tata could pay the award without breaching the central bank’s regulations.

Tata had argued it was not permitted to pay the award since it would be against the regulations.

But in Russia, enforcing awards by international arbitration centres has proven more difficult, said Nicholas Song, a Beijing-based partner at international law firm Dechert.

He noted the 2014 ruling in which the Russian government was ordered by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Netherlands to pay US$50 billion in damages to shareholders of defunct oil giant Yukos Oil, who initiated the case.

The arbitration tribunal found that Russia forced its then biggest oil company – controlled in 2003 by jailed former tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky – into bankruptcy with excess tax claims and forced it to sell its assets to state-owned firms.

The former management of Yukos separately filed in 2004 a claim against the Russian government in the European Court of Human Rights, which awarded Yukos shareholders US$2.6 billion in damages.

Last year, the Constitutional Court of Russia overturned a demand for payment.

“Yukos’ investors have won, but it doesn’t mean the Russian government has paid anything,” Song said.