Can China’s electric car market keep growing if Beijing pulls the plug on subsidies?

The government’s hand-holding is beginning to taper off, with subsidies set to end by 2020. It also plans to penalise carmakers that do not produce NEVs from next year

Brian Gu was at the pinnacle of his 14-year career at JPMorgan Chase & Co., when he left the investment bank to join a start-up, betting that he’ll make a difference in helping Xpeng Motors’ quest to take the EV brand to the world stage.

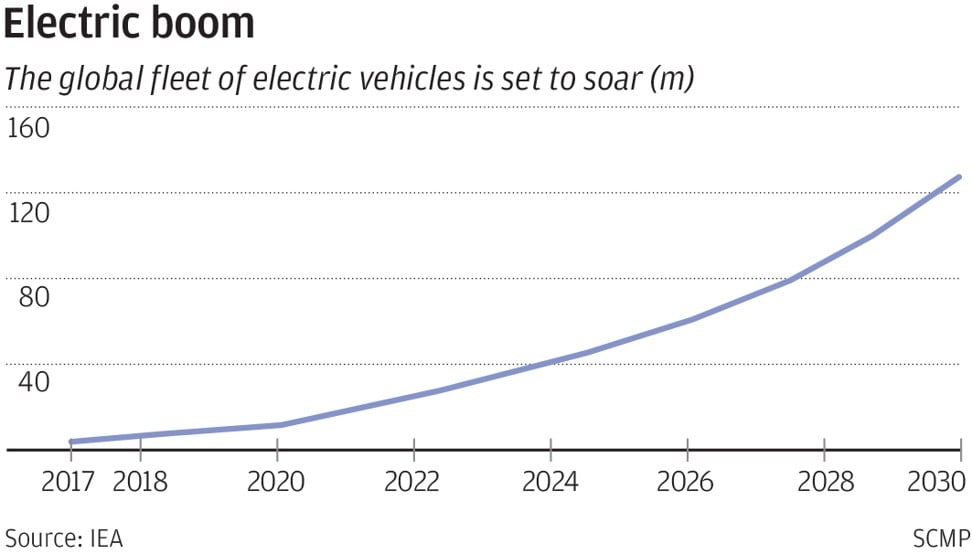

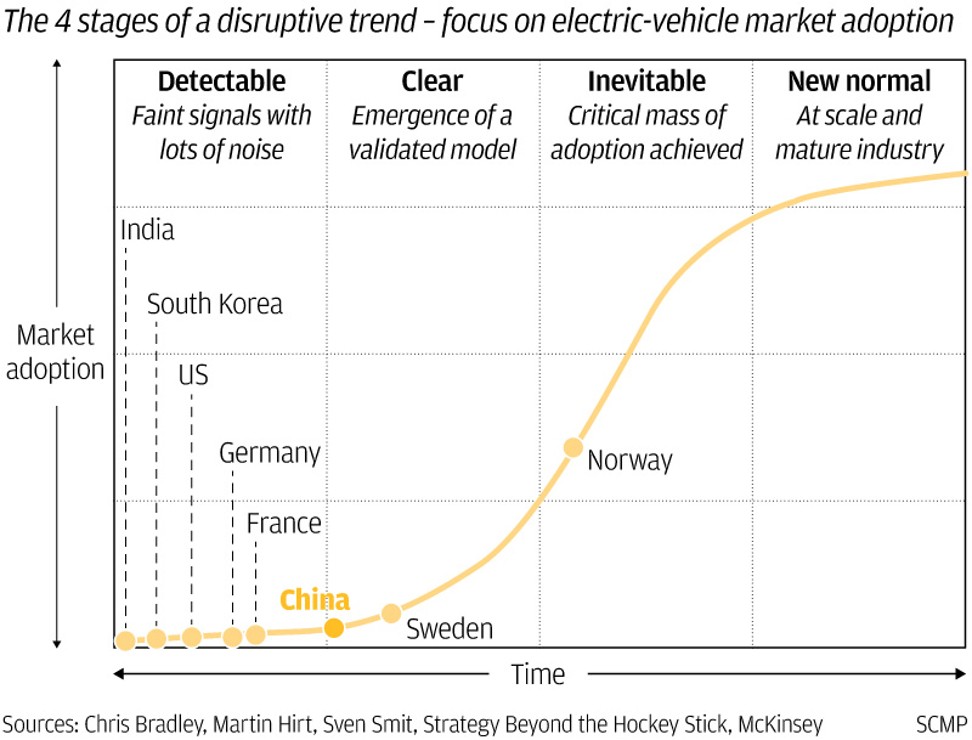

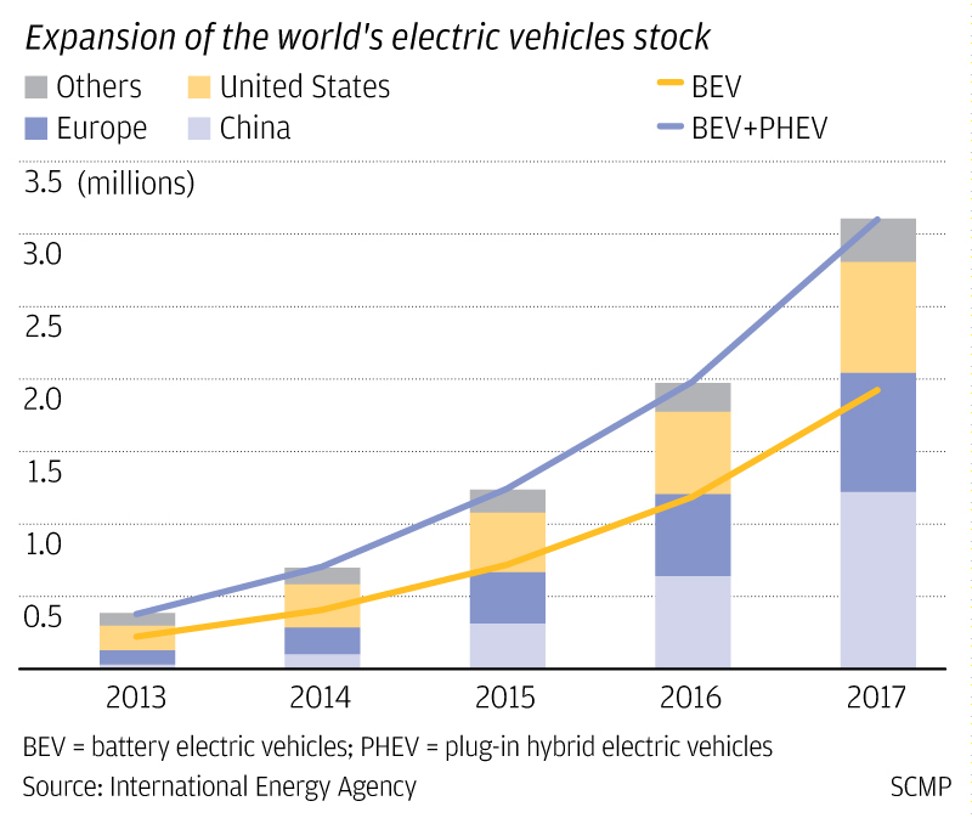

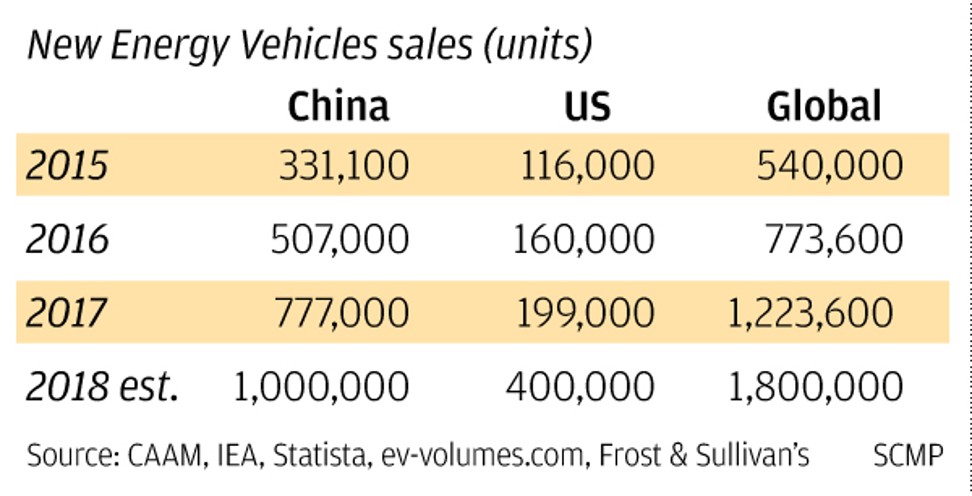

There’s reason for such optimism. McKinsey & Co said under the current growth trajectory, global EV sales would almost quadruple to 4.5 million units by 2020, accounting for 5 per cent of the light-vehicle market.

There’s reason for optimism in Xpeng, seeing that it has the financial banking by IDG, Morningside Venture Capital, GGV Capital and Alibaba Group Holdings, owner of this newspaper.

This week, China’s biggest property developer Evergrande Group paid US$854 million for a 45 per cent stake in a fledging electric vehicle (EV) maker co-founded by former internet star and now blacklisted debtor Jia Yueting.

While sceptics may question Evergrande Health Industry Group’s decision to lend support to Faraday Future, a Jia venture, there is broad market optimism for EVs globally, particularly in China which is the world’s biggest car market.

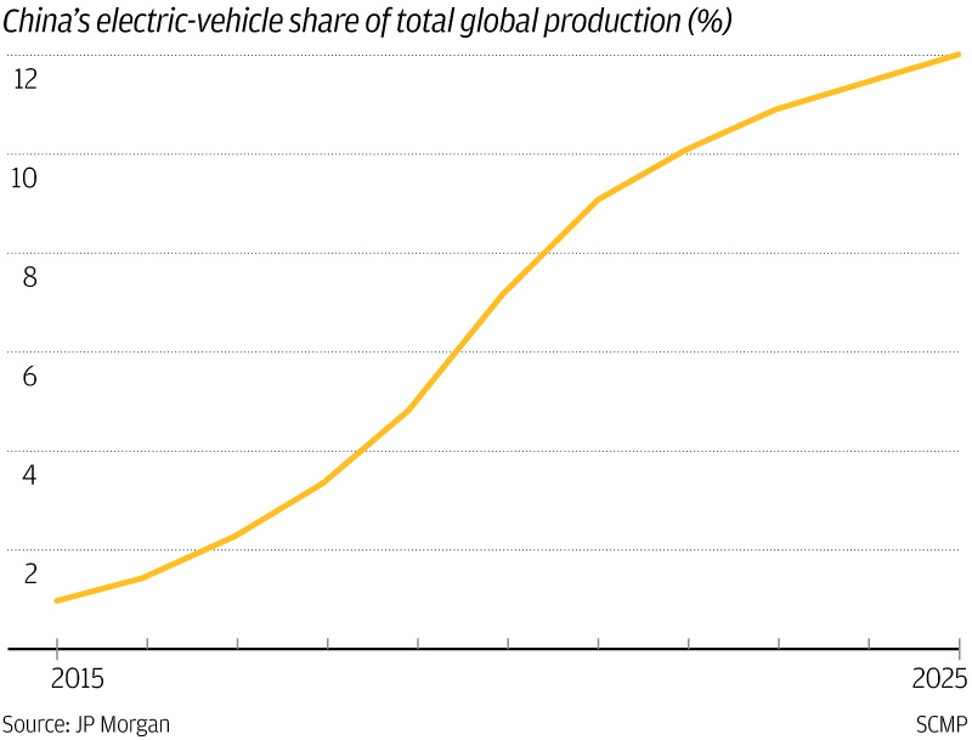

According to JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s 2025 EV Outlook report, robust global growth through 2025 would see China accounting for 12 per cent of the total EVs produced, from last year’s 2.3 per cent market share.

EVs are the answer to four major problems that traditional cars have introduced – traffic congestion, pollution, road accidents, and bad user experience, said William Li, the founder of NIO, a start-up.

As EV design lowers the barrier for making cars smarter, future cars will be self-driven and become a mobile space for living, which provides users ample room to move about, compared to vehicles driven by internal combustion engines.

“If all cars are electrified globally and electricity generated in clean ways, carbon emission will be reduced by 16 million tonnes per day,” Li said at a Shanghai conference earlier this month. “EVs will redefine the fun of owning a vehicle, as they will not only liberate the space, but more importantly our time, bringing us more emotional joy.”

NIO is one of several dozen electric car start-ups that include Byton and Future Mobility to have emerged in China in recent years because of wholehearted support from the government. To encourage growth in the EV market, Beijing has offered research and development grants to carmakers and subsidies to consumers. It has also exempted new-energy vehicles (NEVs) from ownership quotas in the country’s bigger cities.

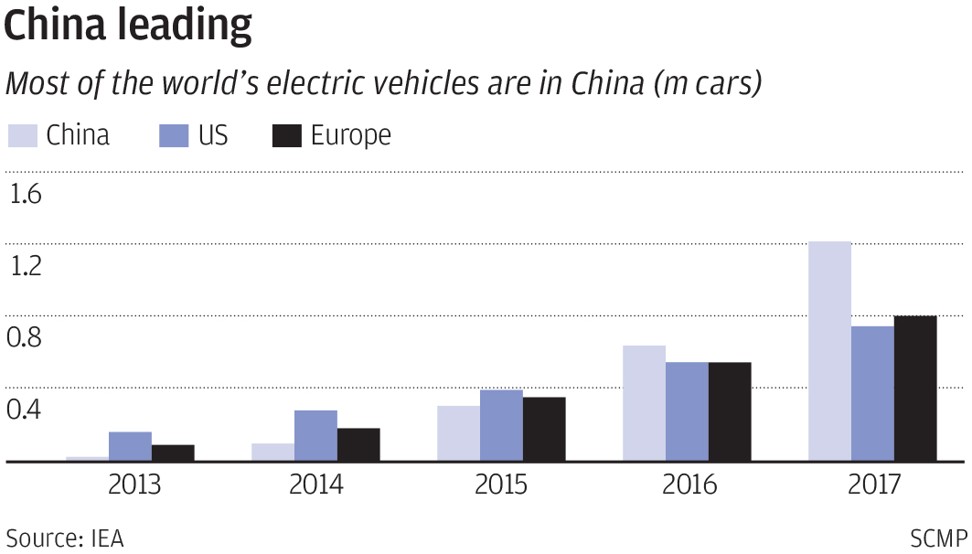

Subsidies, central to Beijing’s grand green quest, coupled with President Xi Jinping’s drive to transform China into a global tech power where NEVs represent the country’s car future, have been instrumental in the country accounting for more than half of the world’s EV sales.

The State Council’s development blueprint on energy saving and new energy car industry projects production capacity topping 2 million units for EVs and plug-in hybrid vehicles by 2020.

The government’s hand-holding, however, is beginning to taper off, and the EV sector needs to brace for complete removal of subsidies by 2020, while proving a viable and scalable business model that creates an ecosystem for the industry to thrive, said analysts.

Since the 2009 pilot scheme of 13 Chinese cities pushing the adoption and ownership of Chinese EVs, a string of tax benefits and exemptions to benefit makers and consumers alike have been rolled out, with regular revision of the concessions.

Unfortunately, NEV sales have not quite matched the official target that the Chinese authorities set between 2013 and 2015, leading officials to encourage the use of these vehicles in the logistics sector in 2015 to in part, to make up the shortfall, according to David Zhang, lecturer at Suzhou Automotive Research Institute of Tsinghua University.

To be sure the 2020 goal is met, authorities have shifted from offering incentives to producers to penalising companies that do not produce NEVs under a set of policies borrowed from California’s Zero-Emission Vehicle programme. Carmakers must generate credits by selling EVs, or buy them from competitors that do. Each EV is assigned a credit value based on range and efficiency, and becomes effective in 2019.

“If your score turns red, you have to spend money to buy such credit, or will have no production quota,” Zhang said, adding that Changan Automobile and Geely Automobile have declared that they are moving to halt production of petrol-fuelled cars.

In China, traditional carmakers have been first-movers benefiting from government subsidies. But it is the upstart EV makers – laggards for now – whose huge ambitions have drawn capital and interest from global big business and some of the mainland’s tech giants like Tencent Holdings and Alibaba Group Holding. Alibaba owns the South China Morning Post.

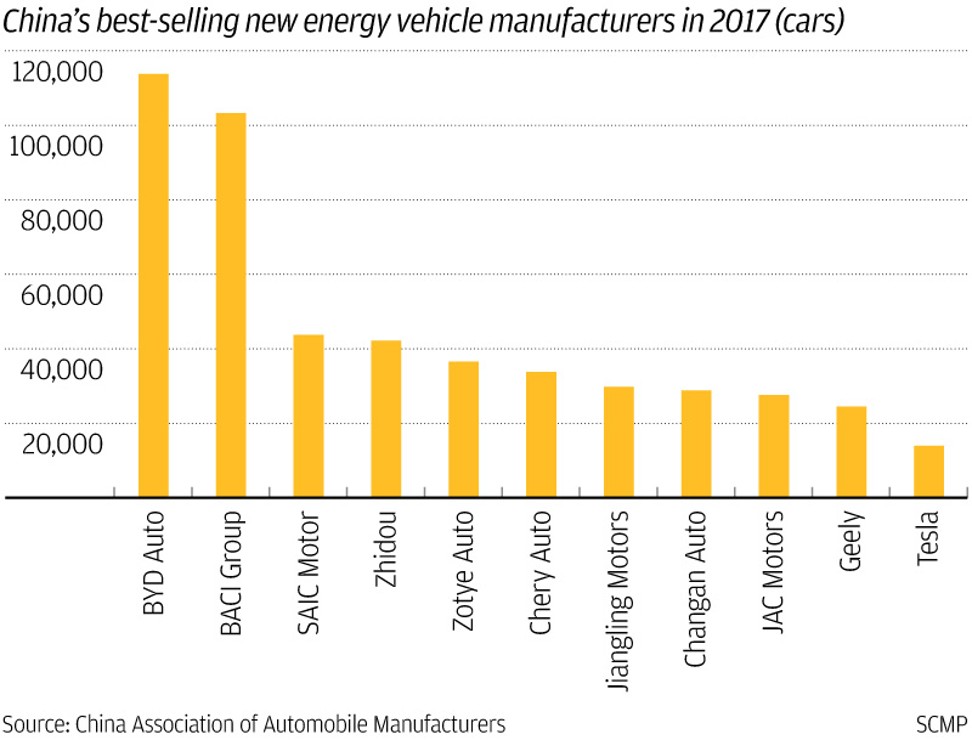

Earnings of BYD, one of China’s leading and pioneering EV makers backed by Warren Buffett, have been squeezed by the government’s gradual cut of subsidies that amounted to up to 110,000 yuan (US$16,600) per unit. Subsequent revisions to the policy ended subsidies for vehicles with a driving range of under 150 kilometres, while vehicles with 300km of driving range will continue to receive the current level of subsidies. Those with driving ranges of over 400km are entitled to even higher subsidies.

Meanwhile, Chinese competitors had better watch out for their overseas rivals who are now allowed to own wholly owned manufacturing units in the mainland. General Motors said it would introduce 20 new-energy models by 2023, and Volkswagen’s luxury Audi division plans to make five such models by 2022.

The subsidies granted by the government made the car’s price look reasonable

On Thursday, the first batch of ES8, a high-performance sports utility vehicle by NIO, rolled off the production line into the hands of outside users (earlier last month several units were first delivered to its employees).

Last year, China sold 777,000 EVs, up 53 per cent from 2016 – more than triple the 200,000 units sold in the US – and is on track to hit the 1 million vehicles mark in 2018.

In the first four months of 2018, the government-backed China Association of Automobile Manufacturers recorded that EV salesreached 225,310 units. The sales volume represented a 149 per cent surge from the year-earlier period, outpacing the 5 per cent rise for the overall 9.5 million vehicles sold, thanks to EV owners like Zhang Wenjie.

Zhang, a Shanghai-based entrepreneur who drives a Roewe-branded EV produced by SAIC Motor, said the choice of a NEV ticks all the right boxes.

“It saved me a lot of time and money in bidding for an car plate,” he said. “The subsidies granted by the government made the car’s price look reasonable. Electricity costs much less than gas.”

Shanghai distributes free car plate licences to buyers of certain NEVs built by domestic carmakers. The lowest winning bid for a car plate in an auction organised by the local authorities stood at 89,000 yuan in May.

Tsinghua University’s Zhang estimated that about 95 per cent of China’s EV owners made the purchase not out of environment awareness, but because of “pragmatic” reasons such as easier access to car plates in big cities.

That remaining 5 per cent would include Yu Xinwei who is budgeting 300,000 yuan to buy his first car.

“I am not going to buy an EV now because I don’t think Chinese-made electric cars are good enough,” said Yu

“I want my car to be a reliable transport tool and will choose a foreign brand car with a combustion engine. In 10 years, I may think about owning an EV if the technologies prove to be mature then.”

With additional reporting by Daniel Ren, and Dorothy Ma