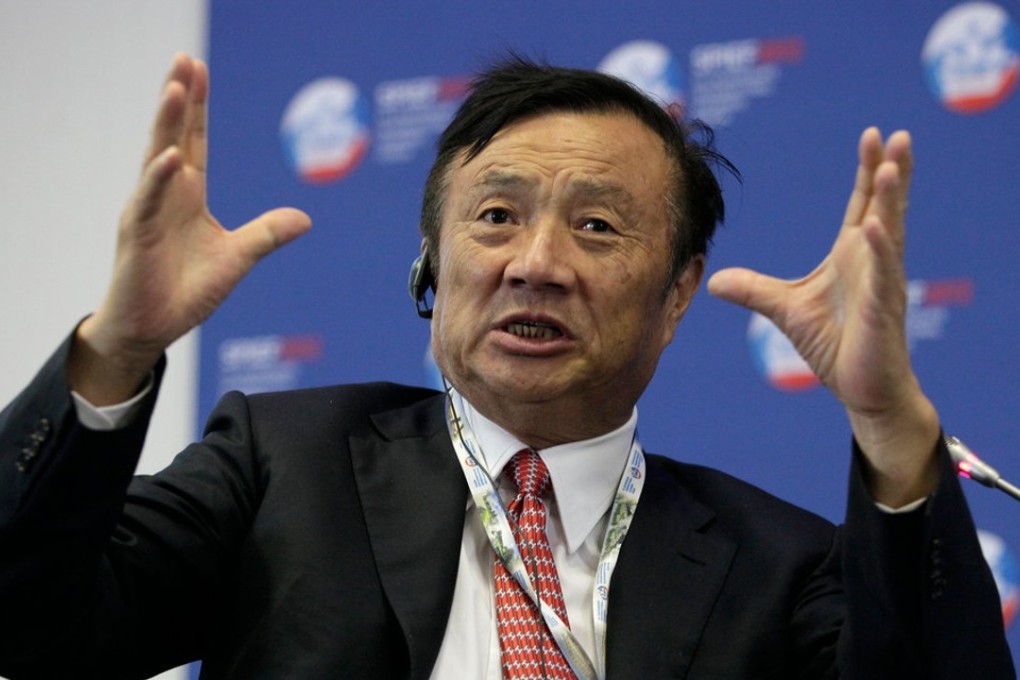

Can Huawei’s founder Ren Zhengfei, who survived a famine, weather Donald Trump?

- With US$92 billion in revenue, Huawei is bigger than Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent combined

- Ren owned 1.4 per cent of Huawei, according to the company’s 2017 report, valuing his stake at US$2 billion

At the sprawling Huawei Technologies campus in Shenzhen, the food court’s walls are emblazoned with quotes from the company’s billionaire founder and CEO Ren Zhengfei.

Then there’s the research lab that resembles the White House in Washington. Perhaps the most curious thing, though, are three black swans paddling around a lake.

For Ren, a former People’s Liberation Army soldier turned telecom tycoon, the elegant birds are meant as a reminder to avoid complacency and prepare for unexpected crisis.

The arrest places Huawei in the cross hairs of an escalating technology rivalry between China and the US, which views the company, a critical global supplier of mobile network equipment, as a potential national security risk.

Hardliners in Donald Trump’s administration are especially keen to prevent Huawei from supplying wireless carriers as they upgrade to 5G, a next-generation technology expected to accelerate the shift to internet-connected devices and self-driving cars.

Don’t ask why US acted against China’s Huawei. Ask: why now?