Hong Kong-based Vistra aims to be one of the global ‘big four’ in the corporate services industry

- The corporate services industry is entering a new era, shedding its association with tax shelters and expanding service offerings, according to Jonathan Clifton, regional managing director, Asia and Middle East, at Vistra

- The industry is in a similar position as the accountancy and tax advisory business 30 years ago, before consolidation created a ‘big four’ of dominant global players

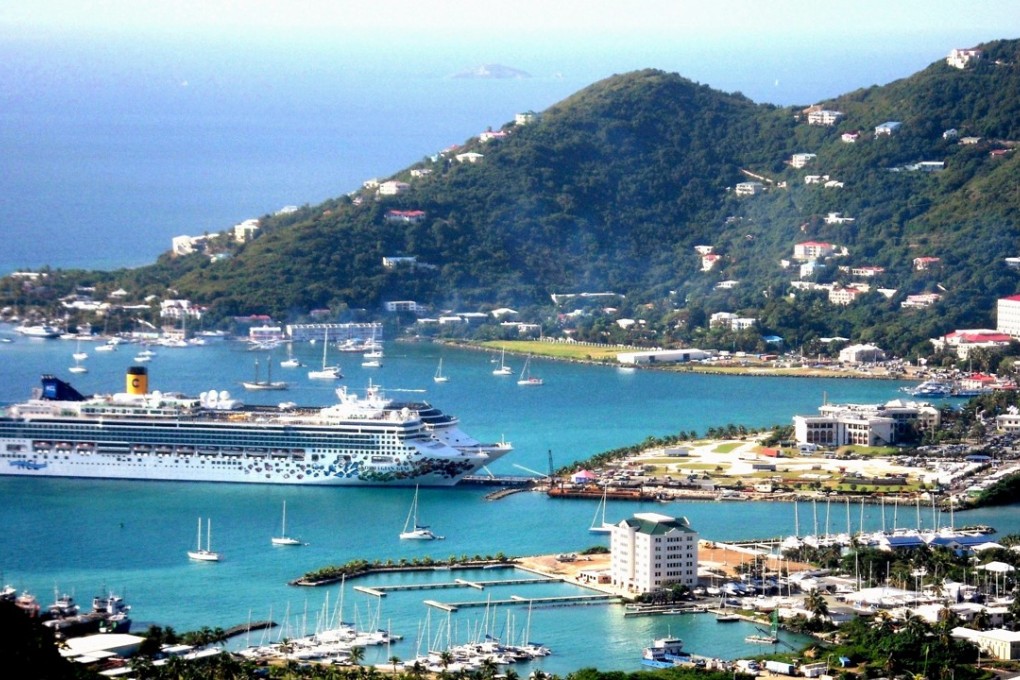

Offshore corporations in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) and the Cayman Islands were once known as the hiding places of money for the world’s wealthiest jet-setters.

That image was reinforced in 2016 and 2017 with the release of the Panama and Paradise Papers, which revealed holdings in offshore corporations and beneficial ownership structures that put wealth beyond scrutiny.

But the corporate services industry, which specialises in such offshore company formations and trusts, is entering a new era of respectability and consolidation, says Jonathan Clifton, regional managing director, Asia and Middle East, for Vistra, one of the world’s largest corporate services providers and headquartered in Hong Kong.

While offshore companies have been used to lower taxes, increasingly, they are being used to facilitate capital flows. For example, joint ventures that are incorporated in the BVI, which means legal disputes get settled under UK law. They are also the means by which international mergers and acquisitions (M&A) might occur, leading Clifton to describe his services as the “plumbing” of international finance.

Vistra’s operations emerged from Hong Kong-based Offshore Incorporated (OIL), founded in 1987, which was a wholesaler of offshore corporate entities. OIL’s founder, Frank Mullens, created a large number of companies incorporated in the BVI on August 8, 1988 (8/8/88), correctly guessing that these companies would then be sold to Chinese clients, thus kick-starting the Caribbean archipelago as a key offshore centre for Hong Kong businesses and private clients.

It is strategically important that when the music stops, we are one of the big players and have created significant barriers to entry

In more recent years, the industry has tried to rebuild its reputation by embracing professionalism and new regulations such as the Common Reporting Standard, which is aimed at transparency.