As the US-China trade war rages, scepticism over Chinese-led deals rises in Europe

- Environment ‘tougher’ as concerns grow among European governments over Chinese efforts to acquire technology leaders

- European Union considering new measures to block deals on national security grounds

A sharp-elbowed confrontation between the Trump Administration and China over trade has weighed heavily on Chinese-led mergers and acquisitions into the United States this year.

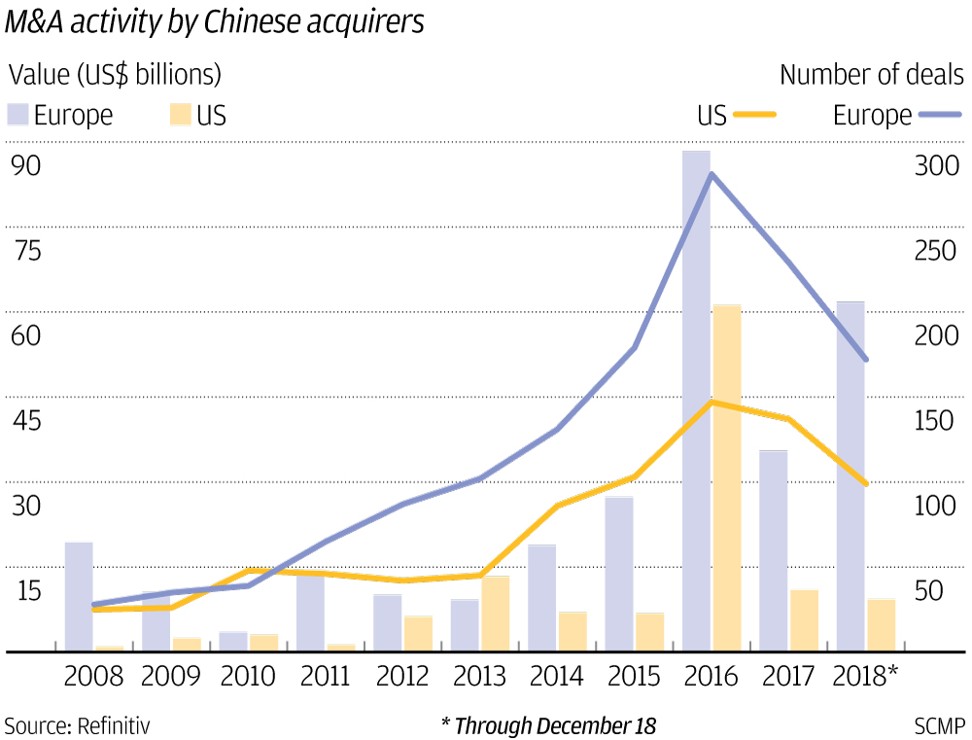

That has Chinese buyers and their advisers looking to other markets for potential deals, particularly Europe, where the overall value of transactions is at its second-highest level in the past decade.

Europe, however, may not be as welcoming a place for future Chinese investments as concerns are growing over the country’s industrial policies, particularly over technology transactions, market observers said.

Chinese oil firm hunts for overseas assets even as deal making falls to 10-year low amid stricter scrutiny

The United Kingdom and Germany have expanded their ability to block deals involving certain so-called critical technologies this year and the European Union is expected to adopt new bloc-wide rules in 2019 that will give countries a broader framework to review transactions on national security grounds.

“Undeniably the climate for China deals in most – though not all – EU members is getting tougher,” said Jacob Kirkegaard, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a Washington think tank. “This is particularly the case for deals concerning technology firms, but in some cases also related to the sales of ‘critical infrastructure’.”

The rising concern in the US and in Europe over Chinese investment revolves around Beijing’s efforts to acquire technology and advance its manufacturing base, personified by its three-year-old “Made in China 2025” programme. The initiative is designed to improve the country’s domestic market share in several high-technology sectors, including robotics and electric vehicles.

The US has cited China’s efforts to remake itself as a hi-tech superpower in imposing tariffs on nearly half of all goods imported from China and in enacting broader reviews of mergers involving critical technologies, such as biotechnology and semiconductors.

In part because of concerns over China’s technology policies, US President Donald Trump blocked Chinese investment firm Canyon Bridge Capital Partners’ US$1.3 billion deal for Lattice Semiconductor in 2017 and Broadcom’s proposed US$117 billion deal for Qualcomm this year.

Deal volumes into the US from China through December 18 this year was down 26 per cent from this point in 2017, and 29 per cent from the same time period in 2016, according to data from Refinitiv, the former risk and financial business of Thomson Reuters.

Undeniably the climate for China deals in most – though not all – EU members is getting tougher

The size of transactions has also declined dramatically in that period, down from US$61.1 billion at this point two years ago to US$9.3 billion in 2018.

As the trade war between the US and China escalated this year, M&A advisers said Chinese companies or investors seeking Chinese money have increasingly looked to Europe over the US because of the greater scrutiny of deals.

Jon M. Herzog, a partner in the private equity and technology companies groups at law firm Goodwin in Boston, said some start-ups are now looking to incorporate outside the US because they intend on seeking funding from China.

“That was highly unusual prior to this,” said Herzog. Western Europe, along with Hong Kong and Singapore, are now prime destinations for new start-ups, he said.

The volume of Chinese-led deals in Europe this year is down from highs set in 2016, before the Chinese government began a deleveraging campaign that has cut into investment outside China.

But, deal flows by Chinese firms in Europe are ahead of historic norms and the value of transactions topped US$61.8 billion through December 17 – more than six times as much as the US, according to Refinitiv.

Chinese deals in Europe totalled US$35.5 billion in the same period last year and US$88.4 billion in 2016, according to Refinitiv. Five years ago, it only topped US$9.2 billion.

Even as the size of transactions has shot up in recent years, European leaders have moved to more extensively review foreign investment and acquisitions around technology.

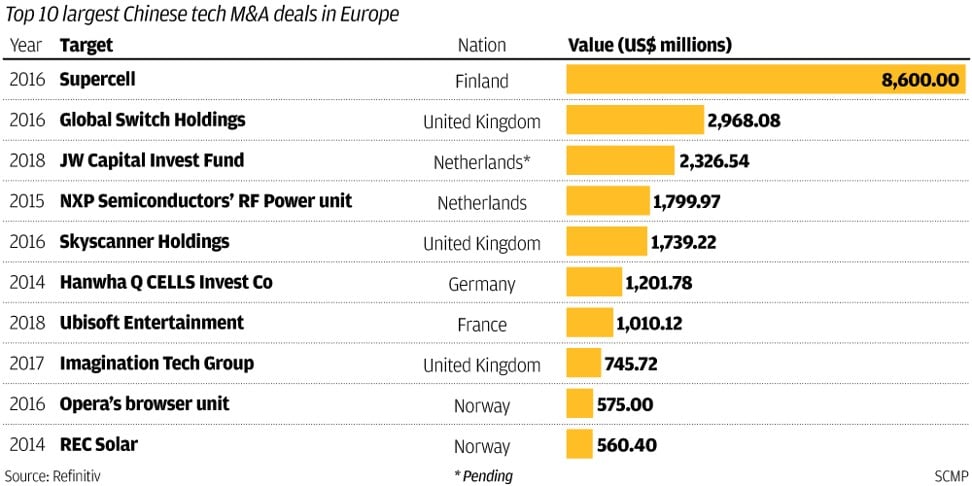

Concerns have been rising in Europe, in particular, since Chinese appliance maker Midea bought German industrial robotics manufacturer Kuka for US$4.6 billion in 2016.

That same year, Germany withdrew its approval for a takeover of microchip equipment maker Aixtron by a consortium of Chinese investors, and questions were raised about who was behind Chinese investments in several German champions, such as Deutsche Bank.

Max Zenglein, head of programme economic research at the Mercator Institute for China Studies, said there is more scepticism in Europe about deals involving Chinese firms.

“The environment has changed,” said Zenglein. “I would say Europe, in general, is lagging developments that have been taking place in the US. In the US, scrutiny of Chinese investment activity has been much more advanced, more intense. I would say Europe is now picking up in this perception on how to deal with Chinese investment.”

In June, the UK, which itself has actively sought Chinese investment in recent years, enacted new rules that would allow it to intervene in transactions that potentially affect national security. These include transactions technology that can be used for military and civilian purposes and quantum computing technology.

Germany also plans to lower the threshold needed for it to be able to review transactions involving “security relevant” companies and deals involving “critical infrastructure”. The German government will be able to review investment stakes of 10 per cent or more under the rule change.

At the same time, a proposed bloc-wide framework for reviewing foreign direct investment in the EU on national security grounds passed an important committee this month and is expected to be voted into law by the European Parliament next year. Whether to conduct a review would remain with individual countries under the proposal.

Growing tension over Chinese investment is already weighing on transactions involving technology, with 19 deals this year versus 37 in 2016 and 33 last year, according to Refinitiv.

Chinese investments in the US shrink 92 per cent as deals come under greater scrutiny amid trade war

“Depending on which member state you look at, there is big differences in perception,” said Zenglein. “If you look at Greece or Portugal or Eastern European countries, they will be much more welcoming to Chinese investments. When it comes to countries that are stronger in the tech area – Germany, France or the Scandinavian countries – I think they do have a different perception.”

M&A advisers said deals involving Chinese companies will continue in Europe and in the US, but will be more challenging in some sectors.

“The EU remains open to foreign investment and adheres to a rules-based approach to transaction review,” said Thomas Gilles, chairman of law firm Baker McKenzie’s China group for Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

“Furthermore, any changes in the foreign investment review landscape will apply to all non-EU investors on a non-biased basis and are not targeted specifically at Chinese investors,” said Gilles. “Investors pursuing transactions in sensitive sectors that could be considered critical to national security should take the potential impact of foreign investment review into consideration early on in the process and plan accordingly, particularly with respect to engaging regulators.”

Robert Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a Washington think tank, said he was sceptical that Brussels will ultimately establish a strong enough review process to check Chinese acquisitions, particularly those subsidised by China’s government.

“While Europe is doing more than it has in past years, it is still doing woefully too little to review and stop where appropriate, Chinese acquisitions of European technology,” Atkinson said. “Some nations, like Germany, understand the challenge, but others, like Italy and Greece, are more willing to focus on the short-term gain from Chinese capital investment, even at the cost of loss of their own and EU competitiveness.”

One thing that may reassure European leaders – Beijing appears to be toning down its Made in China 2025 policy.

For example, Beijing recently omitted references to the initiative from a list of key policies for local governments to focus on next year. The changes come as the US and China recently agreed to a 90-day negotiating period to try to reach a resolution on trade.

Wall Street investors warn that deal making suffers as US stokes anti-China fears

The moves by China to de-emphasise the 2025 programme and level the playing field for foreign firms in China will help ease concerns in the EU, but not as much in the US, said Peterson Institute’s Kirkegaard.

“I think Chinese firms should be perfectly capable of buying new technologies in the open market, but should in general not be able to do so based on subsidised funding from the government – i.e. there are serious competition policy concerns in China – and should not be able to do so in some sensitive sectors that could assist an authoritarian government,” said Kirkegaard.