Will technology or commerce win out as Shenzhen and Shanghai compete to be the model for China’s economic reforms?

- Opportunities await Shanghai and Shenzhen after the Chinese government unveiled blueprints for the long-term developments of the two cities

- Analysts warn that success will only follow if the plans are implemented in full

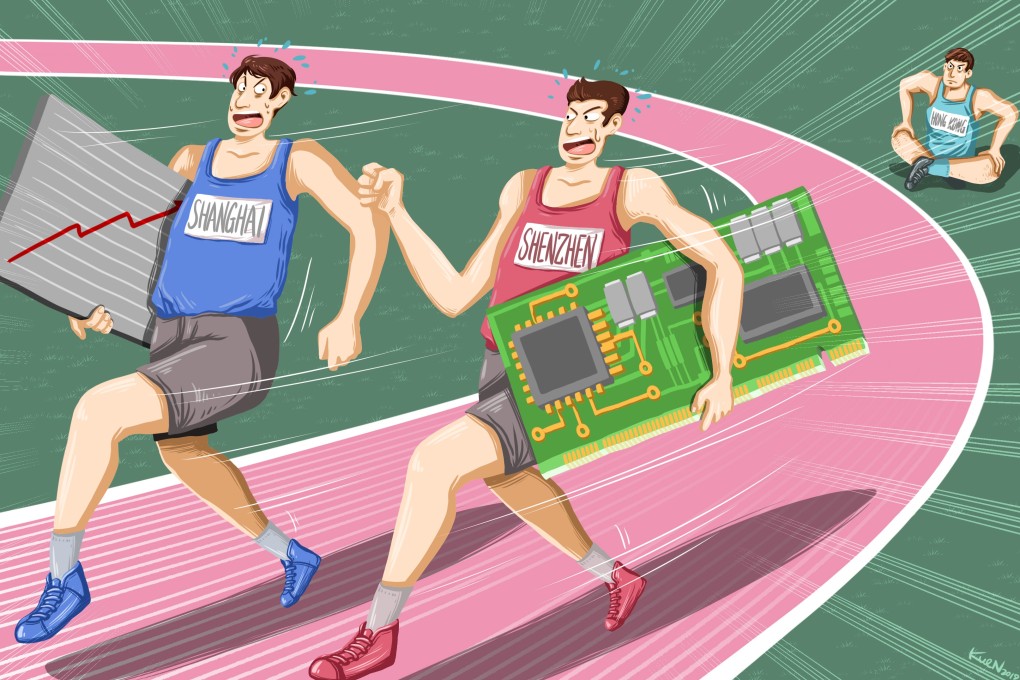

A competition is under way between Shanghai and Shenzhen to claim the mantle as the role model and pacesetter for the next phase of the country’s economic reforms and growth.

The Chinese government has unveiled blueprints for the long-term development of Shanghai and Shenzhen – respectively the commercial hub and “Silicon Valley” of China – granting each leeway to experiment with liberalisation policies and giving them a leg up on hundreds of special economic zones and free-trade zones around the country.

“The blueprints for the two cities are aimed at creating a twin engine for a slowing national economy as the leadership shows their resolve in opening up the Chinese market,” said Yin Ran, a Shanghai-based angel investor focusing on manufacturing industries.

The Shanghai-Shenzhen rivalry is particularly poignant for Hong Kong, as confidence in the special administrative region has been shaken by 15 consecutive weeks of unprecedented civic unrest and street violence, whose roots can be traced to the unease among a portion of the city’s population under China’s sovereignty.

Since an estimated 1 million people marched on Hong Kong’s streets on June 9 to protest against a controversial extradition bill, daily street rallies have descended into violent clashes between police and radical protesters.

Even though Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor has withdrawn the unpopular bill, mayhem has persisted on the streets almost every day, keeping visitors away from the city and causing hotel occupancy, retail sales and property prices to plunge.