What is the future for Hong Kong’s luxury retailers, as China’s big spenders avoid city of protests and coronavirus quarantines?

- Mainland Chinese tourists spent HK$7,029 (US$905) per person in 2018, and made up 78.3 per cent of Hong Kong’s visitors in 2018

- Preliminary data points to impending doom, as the average daily traffic to Hong Kong plummeted to fewer than 3,000 in February, from almost 200,000 a day in the same period a year earlier, according to the Hong Kong Tourism Board

Zhang Zisheng has stopped shopping in Hong Kong. The 24-year-old salesman no longer feels welcome, even if his home in Jiangmen is a mere 90-minutes’ ride away on the high-speed rail, and he speaks the same Cantonese as Hong Kong’s residents.

Zhang’s disquiet matters, because mainland Chinese tourists – and their average spending of HK$7,029 (US$905) per person – made up 78.3 per cent of Hong Kong’s visitors in 2018. Tourism contributed to an estimated 32 per cent of the city’s services output in recent years, up from 21 per cent in 2003.

As Hong Kong shut most of its border checkpoints with mainland China to stop the coronavirus outbreak from spreading in the city, the dearth of visitors is upending the local retail industry. Top-tier designer brands with their loyal legions of customers, fat profit margins and owners with deep pockets may be better placed to weather the slump than second-tier brands that lack the same advantages, retail analysts said. Taken together, this may be the beginning of Hong Kong’s demise as an Asia-Pacific hub for shopping, they said.

“Hong Kong has become less and less of an international retail hub,” said Ashley Micklewright, president and chief executive of the Bluebell Group, a distributor of luxury and premium brands in Asia. “Hong Kong used to be 20 per cent of our Asia business. It’s now 5 per cent. We had more brands in 2013” during the peak, he said.

Hong Kong’s retail sales will shrink by 2.5 per cent to HK$420 billion (US$54 billion) this year, according to a forecast by PwC before the onset of the coronavirus outbreak, which has sickened 53 people with one fatality in Hong Kong at last count. As the outbreak raged on, schools, offices, restaurants and many shopping centres had shut, forcing millions of people to work from home and remain homebound. Mainland Chinese visitors, many of them barred from entering the city, disappeared altogether.

Infographic: All you ever need to know about the global coronavirus outbreak

“PwC expects a continuous tough outlook for Hong Kong's retail market, as a great deal of uncertainty looms over the near future,” said Michael Cheng, PwC’s consumer markets leader for Asia-Pacific, mainland China and Hong Kong, adding that sales of cosmetics stores and department stores are likely to remain lacklustre due to the slowdown of mainland Chinese tourists.

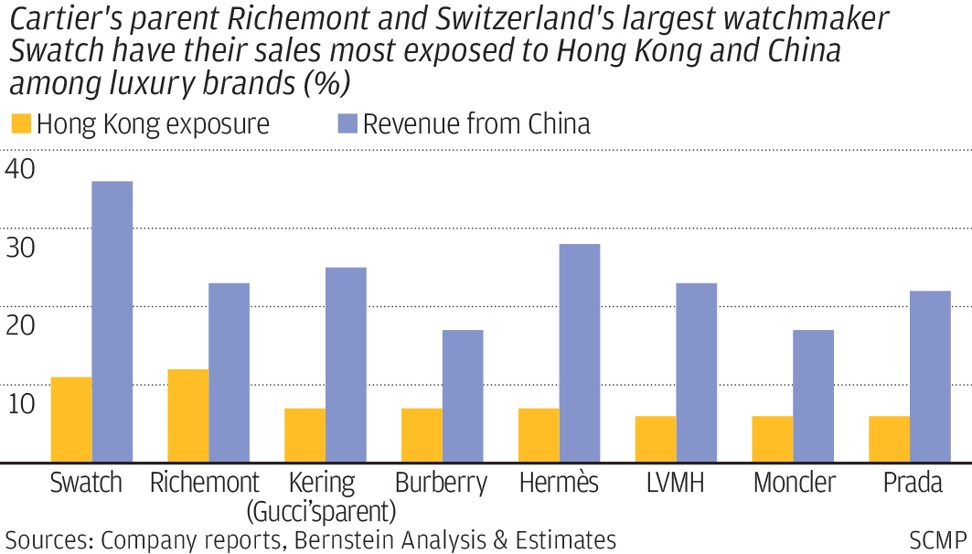

Signs of the decline are everywhere, with high-end brands reporting a 45 per cent decline in third-quarter sales in Hong Kong on average, said Luca Solca, the senior research analyst for luxury goods at Bernstein. LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton, the world’s largest conglomerate of premium brands, slumped 40 per cent during the three months that ended in December.

“A lot of retailers will go under unless there is a significant drop in rental [charges], as many of them were already struggling even before the viral outbreak,” said Alan Lim, founder and chief executive of E-Services Group, an e-commerce service provider. “Otherwise, the retail business [in Hong Kong] has a very bleak outlook.”

Prada and Louis Vuitton were the first to bow to the slowdown in retail sales last year when Hong Kong’s anti-government protests started to turn violent and kept mainland Chinese tourists away.

Causeway Bay landlord cuts rent by 44 per cent as Prada closes store

The retail slump, combined with a mass exodus of brands, would almost certainly put pressure on landlords to cut their rent across all market segments of the retail industry, analysts said.

“Hong Kong is very difficult to make money in, because [retailers] are paying too much in rent, so new projects are [hardly] profitable,” said Bluebell’s Micklewright, adding that about 20 per cent of the brands in his portfolio have left Hong Kong, while another 15 to 20 brands stayed away because the city’s size and costs don’t justify the business. “Our business is growing in the rest of the region because the rents are reasonable.”

The slump in luxury sales is merely the tip of the iceberg for the retail industry, as a citywide lockdown and stay-at-home orders during the coronavirus outbreak kept shoppers away even from neighbourhood malls, restaurants and cafes.

The current slump will be far worse than any previous declines, seen during Hong Kong’s 2003 outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), the 2008 global financial crisis or the 2014 Occupy Central protests, said Micklewright.

Sa Sa closes 21 outlets in Hong Kong, Macau amid coronavirus outbreak

“This is something that could fundamentally change Hong Kong,” he said. “If the tourists aren’t welcomed, why would they come to Hong Kong? So now the retail landlords are going to be facing a major problem.”

“Although no retailers has come out explicitly saying that they are focusing on e-commerce to mitigate the impact of the protests, we have heard that this could be the ‘perfect storm’ for retailers to finally make the necessary investment in online, a boost to Hong Kong’s e-commerce scene, which has always lagged behind other Asian countries,” said Simon Haven, senior analyst at Euromonitor. “In addition, some companies are increasingly starting to think about moving their headquarters to Singapore, which are not limited to retail companies.”

Hong Kong must change its packaging and long-term image as a city, in the aftermath of the controversial extradition bill that sparked off the city’s political crisis and anti-government protests, said Yiu Si-wing, a local legislator representing the tourism industry.

The tax arbitrage that Hong Kong had between the city’s tax-free luxury brands and mainland China’s heavily taxed imported goods was fast disappearing, especially after the Chinese government’s tax reforms last year, he said.

“Tariffs have gradually been reduced in mainland China,” Yiu said, which enables the deep-pocketed Chinese shoppers to “buy more luxury goods on the mainland. The prices [there] will be closer to Hong Kong’s prices.”

Hong Kong could market itself as a short-haul tourism destination, part of the Greater Bay Area cluster of 11 cities in southern China, aided by easy transport. That can augment marketing campaigns that promote Hong Kong as an Events City, and “Old Town Central,” he said.

But all that assumes that Chinese tourists like Zhang will want to return to Hong Kong, once the entry barrier lifts over the coronavirus quarantines, or when the city’s anti-mainland passions subside.

“Everyone thought that things would return to normal once the protests end, but then the virus came as a double blow,” Lim said, adding that a “seismic change has already taken place in Hong Kong’s retailing industry, and more companies will be put out of business. Will the Chinese actually come back once the virus outbreak dies down?”

Ronnie Chan Chi-chung, the billionaire founder of the Hang Lung Group, one of the city’s major shopping centre developers, made a poignant observation about the prospects of returning Chinese visitors.

The secretaries of several mainland Chinese technology executives were accosted and verbally abused by anti-government protesters when they were walking to their hotel in Tsim Sha Tsui.

“If you were them, would you return to Hong Kong?” he asked. “There are so many other places to go in the world. There are countless anecdotes like this, so I personally estimate that the recovery [to Hong Kong’s retail industry] will take a considerable amount of time.”